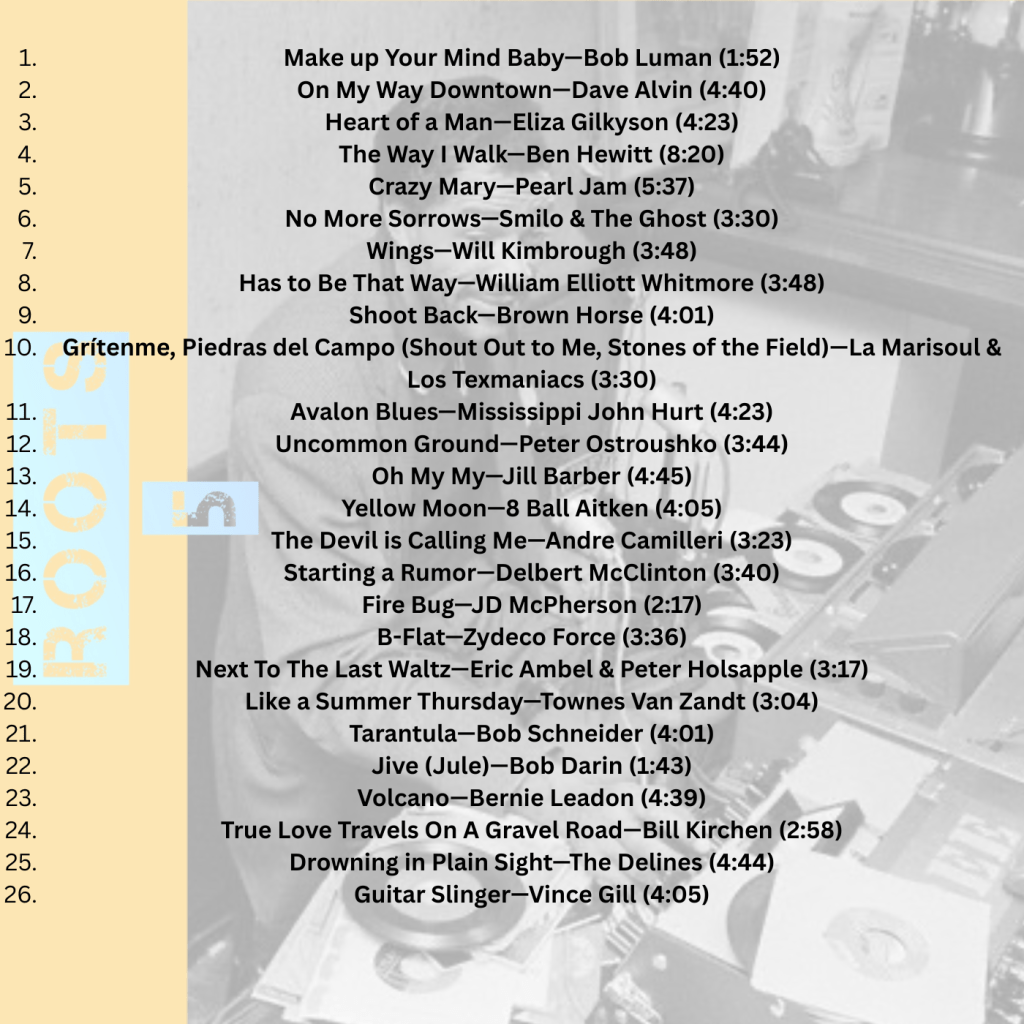

Music you can download to your device

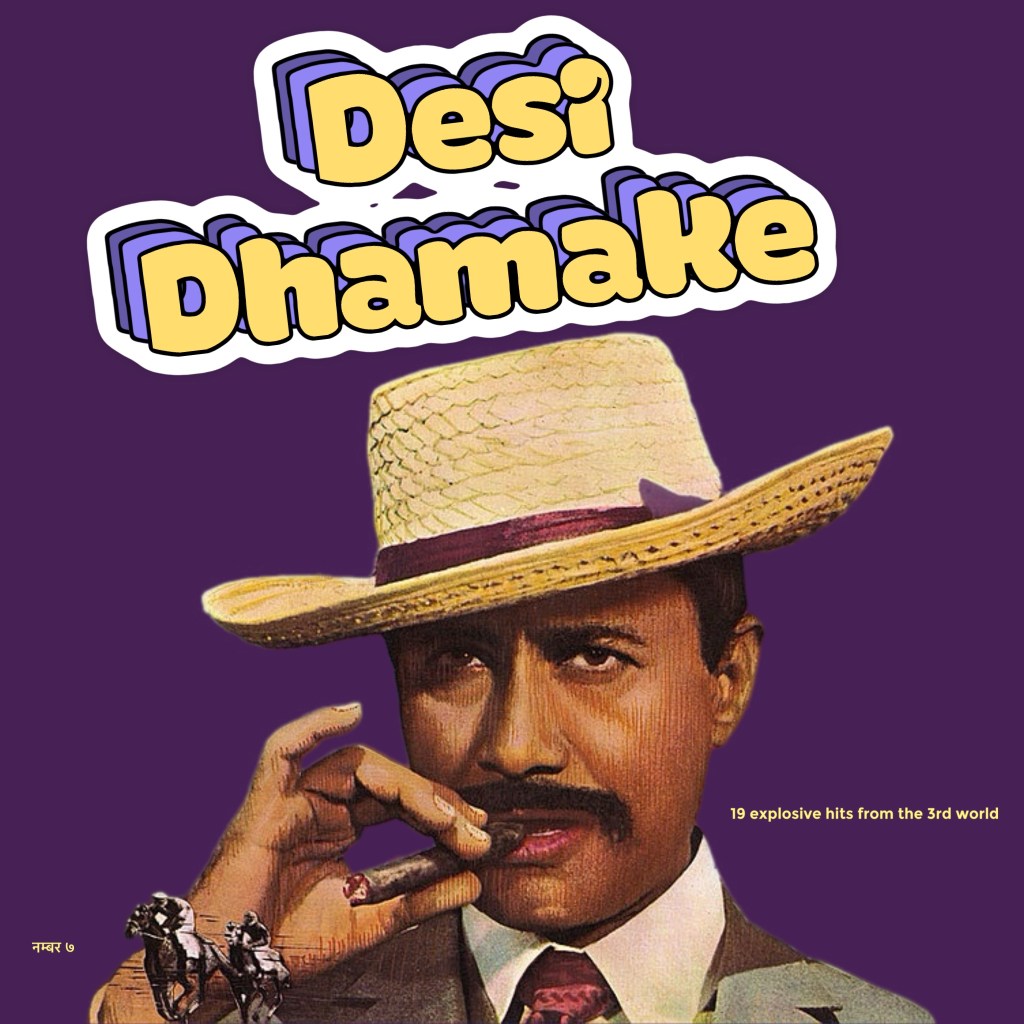

Especially consequential was the emergence of a prosaic marketing gimmick for record stores and music journalists–‘World Music’. A new category for obscure (to Western fans) African and Asian artists, singing in non-English languages.

The music these artists performed and recorded stood out sharply from the pop music of the time (especially, the American variety) with heretofore unheard instruments, revamped rhythms and lyrics in Arabic, Yoruba, Bambara, Zulu, Swahili, Lingala and colonial creoles.

The creation of this immediately contentious category/genre not only gave these artists a legitimate place within European record stores but more importantly, a platform from which they could grow their audiences, make a bit of money and in some cases become internationally feted stars.

In fact, ‘world music’ proved to be a much-needed shot in the arm for a music industry struggling with oversaturation, commercialisation and a technological transition from vinyl to cassette tapes to CDs. African bands and artists took to these new media without hesitation, especially cassette tape, relishing in their inexpensive production costs and portability. Suddenly their music was available everywhere, at home in Africa but also in Manchester, Dusseldorf, Minneapolis and Copenhagen. Fans loved it. And in no small way, ‘world music’, dominated by African sounds and artists, rejuvenated the global music business of the time.

This wasn’t the first wave of African music in Europe. The performers’ fathers and uncles, who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s just as the political ‘winds of change’ blew across Africa, had been the first to introduce African music to Europeans: Congolese rumba, soul drenched crooners from Portuguese Africa, South African jazz, Ghanian highlife. These were the sounds of the dance halls, boîtes (night clubs) and musseques (shantytowns) of Johannesburg, Kinshasa and Luanda transplanted into the pubs and community halls of London, Brussels and Lisbon.

I’m not sure what sort of fan base this first wave of African music had beyond the immigrant communities themselves. Apart from South Africans Mariam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim who enjoyed relatively prominent reputations internationally, few Africans broke into the American cultural mainstream. But given the nature of post-colonial European societies, especially the large number of Africans moving to Europe in the 70s and 80s, Europeans seemed to be quite receptive to this music.

My first encounter with contemporary Afro-pop was in 1991. I was a junior staff member in the UN assistance program in northern Iraq. Living in tents against the side of a brushy hills a few klicks from the Iranian border, our evenings were monotonous. Beer, whiskey, cigarettes and music was about it. The nearest town, Sulaymaniyah, was 90 minutes away by road and in any case, offered no entertainment for European/American tastes.

Every so often we’d roast a wild boar and circle our 4x4s around the fire, open the doors, slip a cassette into the tape player and dance about until the wee hours. On one such occasion one of our Scandinavian colleagues slipped Akwaba Beach into the deck and cranked the volume.

People speak of those lightning strike moments. The Beatles at Shea Stadium. Elvis on the on Ed Sullivan Show. Dylan at Newport. A piece of music and moment in time that changes their lives forever.

The opening notes of Yé ké yé ké with its brazen blasts of brass, rapid fire vocalising and jerk-me-till-I’m-dead rhythms hit me like a bolt from on high. I had never heard anything like this. My entire body felt as if it were captured inside the music. The song sparked every dull, fuzzy and ho-hum part of my experience into a mass of shivering electricity. I hadn’t realised just how much I needed to hear this music. We played that tape over and over for months and the album has enjoyed a permanent seat on my musical security council ever since.

According to our Nordic DJ Yé ké yé ké was not some niche crate-digger’s discovery but a huge hit across Europe. Africa’s first million seller and a #1 hit on both continents. And no wonder.

Mory Kanté was born in Guinea but moved at a young age to Mali to learn the kora and further his family griot traditions. His big break came when he joined the Rail Band where he teamed up with Salif Keita and Djelimady Tounkara as part of the classic lineup of one of Africa’s iconic musical groups. When Keita left, Kanté stepped into the lead singer role before pursuing what came to be one of the most successful solo careers of any African performer.

Akwaba Beach, a dazzling example of Euro-Africaine dance/club music, opens with the #1 smash hit Yé ké yé ké and continues in the same upbeat vein for the rest of the album. Fast moving synth pop mixed with Kanté’s thrilling tenor voice, punchy kora riffs, blaring brass, feisty backup choruses led by Djanka Diabate and the percussion riding high in the mix. Dance music distilled to its essence.

Released in 1987, Akwaba Beach pounds with drum machines and shimmers with the synths that dominated the music of that decade. But unlike a lot of other relics of the 80’s, these machine instruments fit Kanté’s music to a ‘T’. It is the cocky, blatant sound required when performing in a crowded, noisy club. Unapologetic disco. If you’re looking for folk-lorish ‘authentic’ African music, you’ve come to wrong place. Kanté’s singing and playing is so good, his musicians so tuned into his vision, all that matters is the quickening of your blood.

Akwaba Beach shot Kanté into outer space as a world music superstar and opened the field for other Africans to experiment and go boldly into new territory.

__

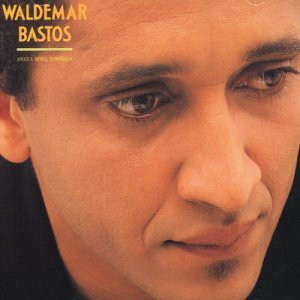

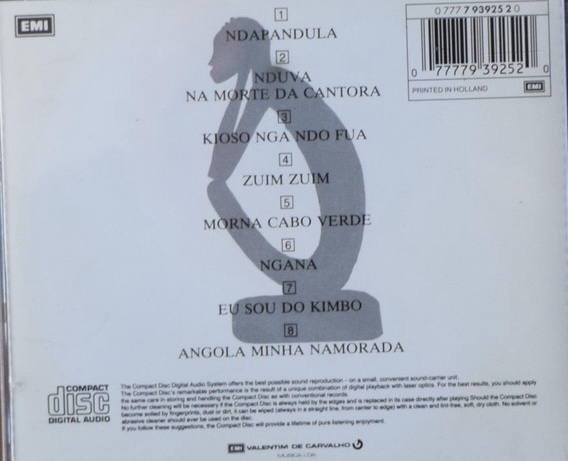

On the other end of the BPM spectrum is Waldemar Bastos’s 1990 album, Angola Minha Namorada (Angola, My Beloved). Recorded in the picturesque Portuguese coastal town of Paco D’Arcos and released in 1990, this music is urbane and sublime. There is none of the frenetic energy of Akwaba Beach within 100 miles.

Waldemar Bastos, who passed away in 2020 was born in colonial Angola in 1954. Like so many creative Angolans, he self-exiled himself from his country to settle in Portugal after it became clear that the revolution was willing to strike down musicians and other artists, not just ideological opponents. Music had played a huge part in mobilising the Angolan people to support the anti-colonial revolution, but many popular singers and musicians found themselves caught up in the 27th of May 1977 purge unleashed by the ruling Marxist-Leninist party in reaction to an internal ideological challenge. Within 18 months of securing independence, artists and musos were realizing that the dream was turning into a nightmare. Bastos left his homeland in 1982, aged 28.

Blessed with a warm and supple voice not dissimilar to that of Al Jarreau, Waldemar was considered in his lifetime a giant of Angolan music. His album, Angola Minha Namorada, was released nearly a decade before Pretaluz, the record that saw him “breakthrough” to European and American music fans in 1998.

It’s a gorgeous album. Calm, somewhat laid back in pace but deeply felt lyrically and musically. This record is the thing you want to listen to on late Sunday morning. When there is no reason to rush, nowhere to go and everything to be gained by letting Waldemar’s soulful voice slowly insinuate itself into your being. Hues of fado and tints of jazz colour this beautiful music. Though entirely different from the club music of Mory Kanté this album is another fine example of Euro-Afro pop.

Yesterday was the biggest day on Melbourne’s sports calendar, the Australian Football League’s Grand Final. This year the pre-game entertainment featured none other than Snoop Dogg. A controversial choice to be sure. But then so was Meatloaf back in 2011. Ranked as one of the stupidest moves by the money fiends that control Australia’s beloved, unique form of football, Meatloaf’s appearance was hated by fans (Meatloaf’s included) and forced the Has-Been to publicly apologize for his poor outing.

It’s the Australian way it seems when it comes to welcoming international superstars. There was Judy Garland in 1964 (deprived of her pills by Australian Customs) who refused to leave her hotel for three days. And Joe Cocker busted a few years later.

In 2015, Johnny Depp and his girlfriend, Amber Head, were forced to grovel in front on our media and courts to express their regret for failing to declare two pet dogs that accompanied them, thereby avoiding the usual 10-day quarantine. At one point the fiery (and often inebriated) Minister of Agriculture, threatened the dogs with pet-euthanasia, if the Hollywood power couple refused to pay public penance. In the words of Depp, “when you disrespect Australian law, they will tell you!”

Frank Sinatra would have 100% concurred with that statement. Perhaps of all the superstars we’ve harassed, it is somehow appropriate that The Chairman of the Board’s experience sits at the very top of the list.

Frank first toured Australia to in 1955. But from the moment he and 14 year-old Nancy stepped off the plane at Melbourne’s Essendon airport, he was met with derision. Fans who had gathered at the airport hoping to share a bit of banter with their hero, quickly turned hostile when he managed but a single wave and half a smile before stepping into a limo and being whisked away to his hotel. From Cheers to Jeers went the headlines.

The shows themselves went off a treat. Fans raved how he sounded just like his records. Motorists passing by the West Melbourne Stadium double parked as his voice carried out into the street. A triumph all round. Frank loved Melbourne, the fans loved Frank. The (lack of) incident at the airport the day before was forgotten. After all, it had been announced that Sinatra would appear at his hotel for breakfast; fans would surely be able to get a second chance to hear him speak to them.

Alas, the headlines the following day read: Frank Sinatra Fans Miss Out Again. The hotel’s manager was given the task to confront the angry fans and chock it up to a ‘misunderstanding’.

Two years later, a second tour Down Under was scheduled but Ol Blue Eyes abruptly turned around in Honolulu. Apparently, Frank’s decision was based on the fact that sleeping arrangements for his musical director had been overlooked for the onward journey to Australia.

Seven shows were cancelled leaving his promoter the ugly job of refunding 23,000 tickets to ever-more cheesed off Australian fans. In January 1959, Frank tours again. He’s still stand-offish in public but in outstanding form in his shows which are supported by the Red Norvo Quintet. His private life is dominated by his unsuccessful attempts to regain the love of Ava Gardner, who just so happened to be in Melbourne as well, filming (with Fred Astaire and Gregory Peck) On the Beach. When a reporter in Melbourne dares to ask him a question, Sinatra grunts, “Misquote me kid, and you’re dead with me. In fact, I’ll sock you on the jaw.”

On the 1961 tour he ignored Melbourne altogether, doing four shows in Sydney and then flying back to familiar Californian shores.

Things got completely crazy in 1974. After being tsunamied by rock ‘n roll for most of the previous decade, Frank was finding a fresh relevance. He was out and about. Touring the world. Australian fans once again forked out their new Aussie dollars to spend an evening with their Man.

On 7 July, Frank flew into Sydney as grumpy and aloof as usual. Plane to Rolls Royce to Hotel. Nary a smile or wave to his adoring fans and a press corps salivating at the prospect of a scandalous headline or so.

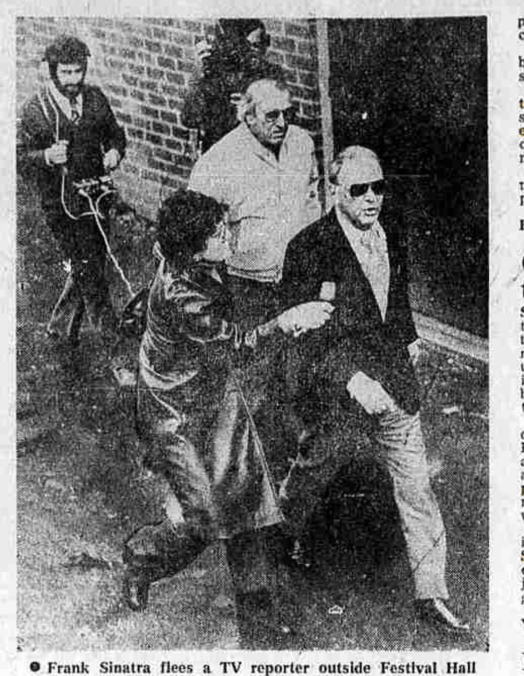

On 9 July, Frank’s arrival in Melbourne was memorable in the main for his refusal to acknowledge the press and shoving a fan out of the way. So harassed did he feel that he ran from his private jet to the awaiting limo. So far, typical Frank behaviour.

At that evening’s show at Festival Hall, Frank’s first appearance in the city in fifteen years, he delivers what is now considered one of his best live performances. He’s relaxed, his voice is as good, if not better than it’s ever been.

So relaxed was he that in his first monologue Frank sums up his views on the local press. Horrified and shocked, a couple of local unions (The Professional Musicians Union and the Australian Theatrical and Amusement Employees Association) announce that his second show, scheduled for the following evening, would be cancelled unless Ol’ Blue Eyes issues an apology. This demand is met with scorn by Sinatra and his entourage. The press, he said, owed him an apology for 15 years of treating him like “shit”.

Now other unions pile on. Frank is not permitted to leave his Boulevarde Hotel room. He places a call to his pal, Hank, aka Henry Kissinger, asking him to intervene. Word on the street has it that Jimmy Hoffa has also been contacted to threaten his Aussie counterparts. An international incident is brewing.

The foam in the mouths of the press can no longer be hid. After the first show in Melbourne, his bodyguards, beefy mafia types, assault a news cameraman nearly chocking the man to death. The unions respond with a ‘black ban’. He is to benefit from no public services whatsoever. No security. No police escorts. No room service. No fuel for his plane. No passport checks. Nothing. Frank Sinatra is a prisoner.

The overlord of all of Australia’s powerful trade unions, a certain Bob Hawke, is persuaded to step in. In the initial meeting neither party budges. Frank sends word to Hawke, “I’ve never apologized to any one and I’m not about to start now.” As the unions huddle Sinatra’s entourage sneak him out of the hotel and race to the airport where the media reports, he will meet with Hawke. But his private jet defies air traffic control and takes off to Sydney, leaving an embarrassed and royally pissed off Hawke looking like a chump.

Unfazed but seething, Hawke flies up to Sydney. In response to Sinatra’s lawyer’s demand for his plane to be refueled, Hawke delivers a classic Aussie ultimatum. This brings the Chairman of the Board out to meet Hawke for the first time. Hawke issues his ultimatum again to the Man himself. After several minutes of ‘nattering’ Sinatra returns and asks Hawke for suggestions of what to put in the apology. Within an hour or so they agree on the words, and Frank’s lawyer descends to the press and reads the statement. Frank Sinatra apparently “did not intend any general reflection upon the moral character of working members of the Australian media” and regretted both “any physical injury resulting from attempts to ensure his safety” and the inconvenience to patrons.

A few days later at Carnegie Hall, Frank told his audience, “A funny thing happened in Australia. I made a mistake and got off the plane.” He then went on to target Rona Barret, a prominent female journalist of the day, by saying, “What can you say about her that hasn’t already been said about… leprosy?”

As it happens, Snoop Dogg’s show was the bomb. Most punters on social media are saying it’s the best show the AFL has ever put on. As for Frank, well, he did return to Australia 14 years later, in 1988. Bob Hawke was now Prime Minister. Upon arrival Frank meets with the press and even poses with the ‘bums and parasites’. He may have been an asshole but he was no dummy.

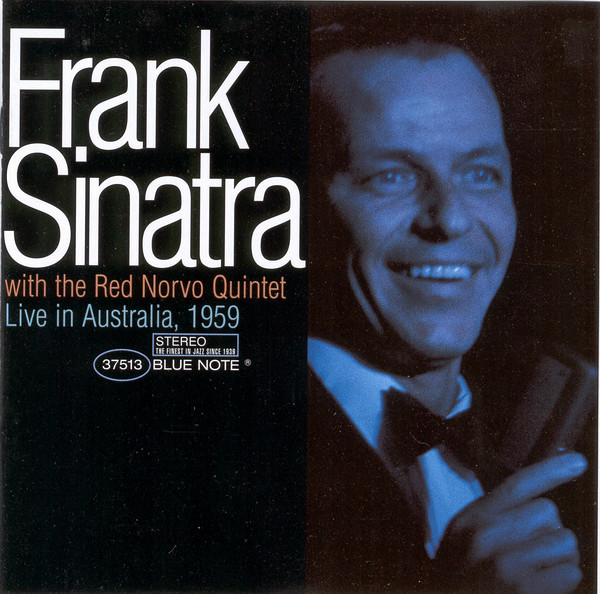

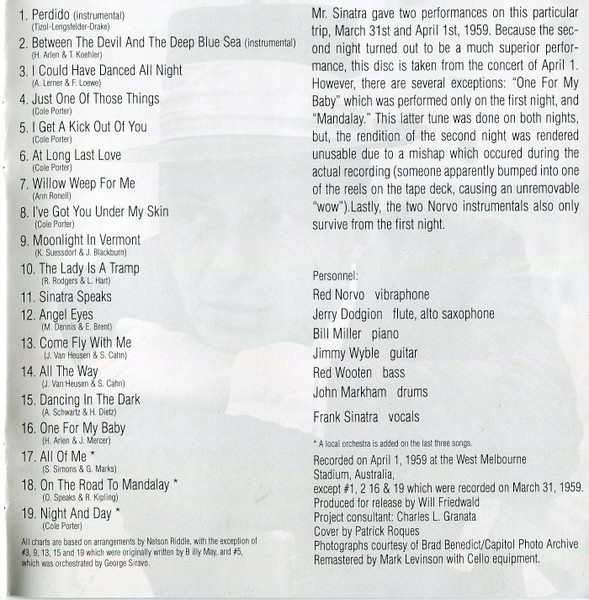

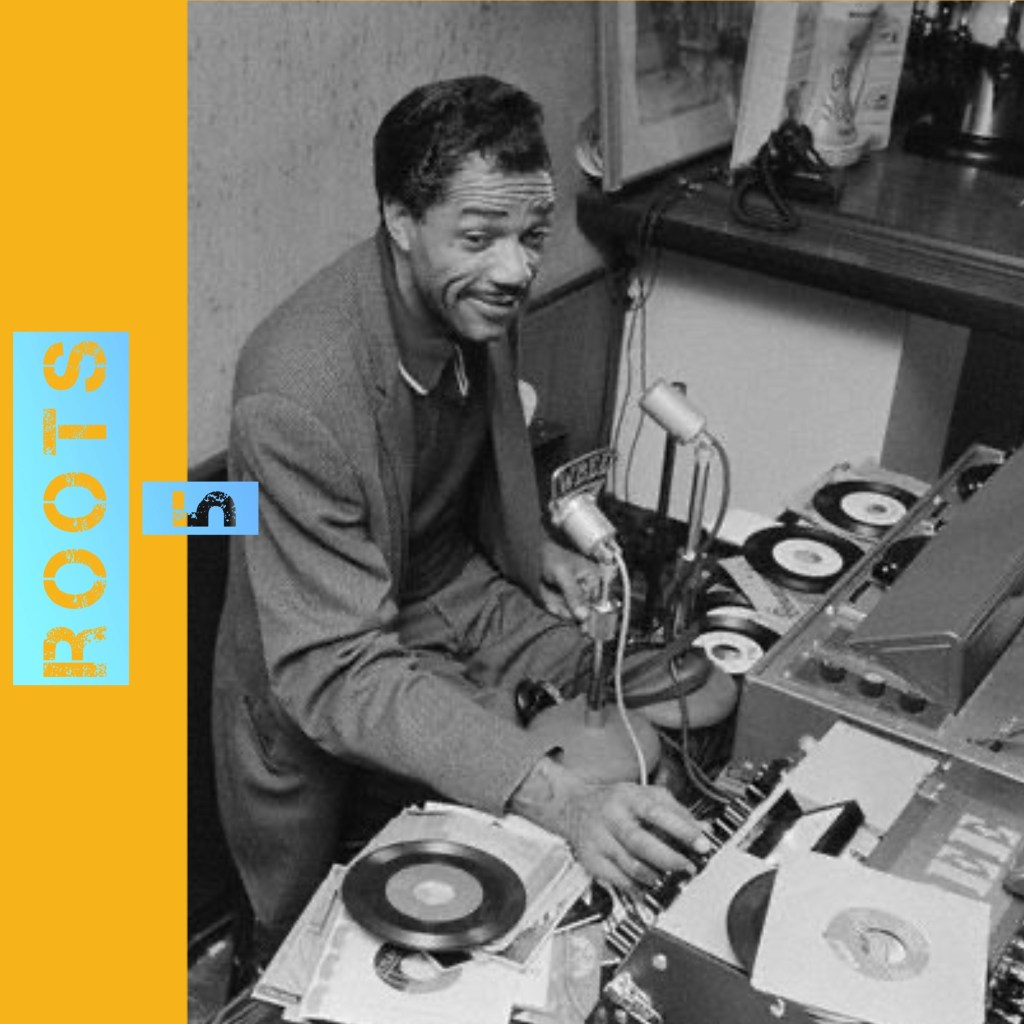

Here is the famous first Melbourne show in March 1959.

Long the favorite of collectors, who have cherished their bootlegged copies of the concert for years, Frank Sinatra with the Red Norvo Quintet — Live in Australia 1959 was finally released officially in 1997, nearly 40 years after the concert was given. In many ways, the wait was actually positive, because Sinatra’s loose, swinging performance is a startling revelation after years of being submerged in the Rat Pack mythology. Even on his swing records from the late ’50s, he never cut loose quite as freely as he does here. Norvo’s quintet swings gracefully and Sinatra uses it as a cue to deliver one of the wildest performances he has ever recorded — he frequently took liberties with lyrics while on stage, but never has he twisted melodies and phrasings into something this new and vibrant. The set list remains familiar, but the versions are fresh and surprising — “Night and Day,” where the song is unrecognizable until a couple of minutes into the song, is only the most extreme example. And the disc isn’t just for the hardcore fan, even with its bootleg origins and poor sound quality — it’s an album that proves what a brave, versatile, skilled singer Sinatra was. It’s an astonishing performance. [All Music Guide]