Trying to untangle my family’s German Russian roots

What I know or thought I knew about my father’s family line was the following. Dad’s dad’s arrived in America as a very young boy in the company of his mother and older brother, Uncle Julius, around 1906. They somehow ended up in the flatlands of North Dakota where grandpa grew up, became an itinerant preacher, a sort of Methodist circuit rider, raised a large family of nine children, with Dad stuck in the middle at number 4, moved to the suburbs of Los Angeles where some of his children had settled, got cancer and in 1955 passed away two years before I wandered onto the stage.

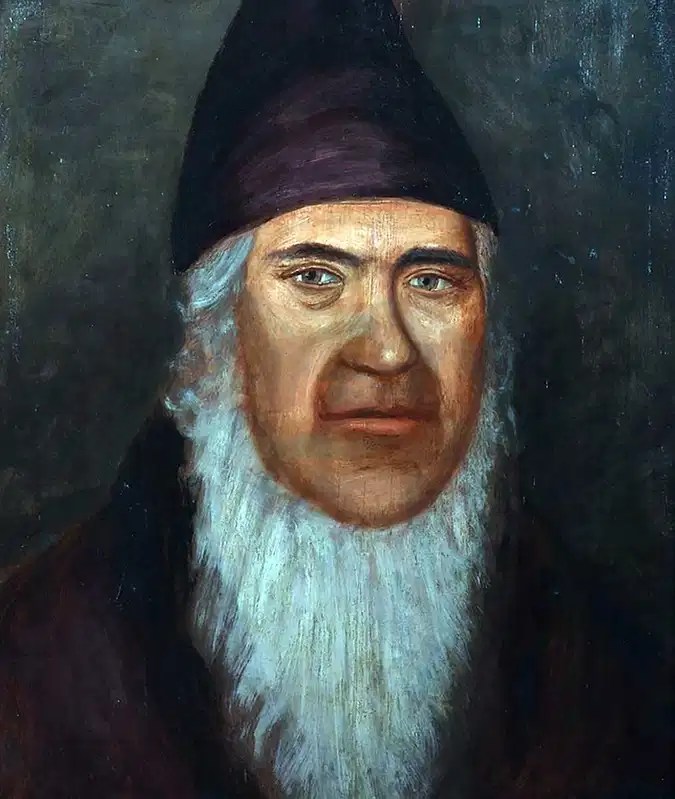

Grandpa was German and had come from that vague geography known as Prussia. ‘Around Danzig,’ I would tell people. That’s it. The history of the Rudolph Rabe line was a concise one. It began somewhere in the eastern German lands, beyond which stretched a vast, silent horizon of Nothing.

There are cousins who have done some research and who have known more than this for a long time. But as I have lived in distant lands, far from the continental USA, for most of my adult life I have not been privy to family gatherings where such tales and faded photographs are shared. To be honest, the thumbnail history I’ve just retold was sufficient for my purposes. I never met grandpa Rabe and had little curiosity about exact details.

__

It’s inevitable that a day would come when I would want to know more. I’ve spent a lot of time throughout my life thinking about the sort of family I was raised in. At various times I’ve tried to write about being raised in India as a missionary kid. Or being raised as an evangelical preacher’s kid. Having studied history at university I am always interested in the ‘but why did that happen?’ questions. Once I make sense of one part of the story, I like to zoom out a couple layers and see the wider view and understand the context.

When Dad died in 2018, I did a bit of reading on the Holiness movement, the cultural pond he was spawned and swam around in as a child. Camp meetings ‘down by the riverside’ featured bigly in this history; both dad and mom talked about the Watson Camp Meeting in southern Minnesota where they met and where Dad was inspired to pursue a career as a missionary in India.

Dad and Mom jointly wrote a memoir of their life together in which grandpa Rabe’s history was covered off in the first two paragraphs. Grandpa was born in Poland of German parents wrote my dad, which helps to explain why Danzig always popped into my head, as that city’s name in Polish is Gdansk, which everyone got to know through the Solidarity movement in the early 80s.

Grandpa had kept a diary for some years in which he talked about his life as a poor Methodist preacher in the Dakotas, Montana and Minnesota. I read it but don’t remember him shedding any light on his childhood, family or history in Europe. What was interesting about his diary was his obvious total commitment to his Christian faith. That fit in well with my own experience. His son, my dad, who shared his name, Rudolph, was also a barnacled believer in Jesus. Like father, like son. Senior and Junior.

Together the memoir and diary added a lot of color to my imaginary family portrait. I got a glimpse of how financially unstable grandpa’s upbringing had been. And how that continued for most of my dad’s childhood. The diary revealed grandpa to be a man tormented by regular and frequent emotional highs and lows. He was, it seems, a manic depressive. Many of my immediate family, including myself, have also battled with the Big D and other mental illness avatars. I was starting to feel more connected to this guy.

As for his religion, I began to understand just how specific a world it really was. The Holiness Methodist churches in which he preached were small, rural and probably quite marginal as far as the broader German community went. Most parishioners were farm folk who clung to their German lifestyle and language, mainline Lutheran mainly but also some Catholics. Grandad’s family appears to have come out a Pietist dissident movement whose adherents migrated from Germany to the Black Sea regions of southern Russia in the early 19th century.

Here was a thread that tied together my own strong evangelical upbringing back into a history of a particular religious group who espoused many of the same principles that both Rudolphs held dear.

__

There was this guy named George Rapp who lived in the German-speaking state of Württemberg. Rapp believed he was a prophet and when he said as much in front of the Lutheran church hierarchy he was jailed and quickly thereafter, gathered some followers, who like him believed that Christ’s second coming would take place in the United States, fled Württemberg for Pennsylvania. There, he established a community–the Harmony Society–that emphasised separation from the world of non-believers (enemies number 1 and 2 being other Christians), personal holiness, celibacy and communal ownership of community assets.

Influential in his time as a radical Pietist [1] among similar ‘evangelical’ sects, denominations and communities but also with some important early figures of the Methodist movement in the US in the early 1800s, he once met the President, Thomas Jefferson, who personally interceded with Congress to allocate 40,000 acres of land for Rapp to establish his spiritual colony.

If he lived today, he would be called a cult leader and be the subject of a Netflix documentary. In addition to believing in the second coming, personal sanctification and wealth accumulation (which Rapp somehow believed was essential to winning Jesus’ favour upon his return), the Rappists as they were sometimes called, believed in alchemy, direct communication with God and submitted themselves to complete domination by Father Rapp. In the words of a journalist at the time, “The laws and rules of the society were made by George Rapp according to his own arbitrary will and command. The members were never consulted as to what rules should be adopted; they had no voice in making the laws.”[2]

What does this have to do with the European phase of my family history? Maybe nothing, as I’ve not read much on Rapp and the whole Pietist movement that came out of the Lutheran church in Württemberg. But the link between this radical evangelical, holiness-focused cult with the growth of Methodism, especially among German speaking immigrants in the States, is interesting. To what extent (if any) was the Holiness Methodist denomination, in which grandpa preached and in which my Dad and his siblings, as well as Mom’s family were raised, influenced by Rapp and his teaching?

Even more interesting is that the surname Rapp is closely connected with the surname Rabe. They both trace their origins to the Middle High German[3] word ‘raven’, hence a nickname for someone with black hair or some other supposed resemblance to the bird.[4] Though Rapp has become its own family name, it was originally an abbreviated form of Rabe (Raabe).

The third thin but interesting thread of this tapestry is that our step Great-Grandfather, husband of Grandpa Rabe’s mother at the time of their arrival in the States, Frederick Kenzle (Kingsley) a.k.a. “Grandpa Fritz”, according to family conversation, was born in a village called Hoffnungstal, in the Bessarabian region abutting the Black Sea.

So what?

Here’s what.

George Rapp was not the only religious radical dissident to take leave of Württemberg in the early 19th century. The Holy Roman Empire State of Württemberg, in the southwestern corner of modern Germany, was one of the first States to embrace Luther’s Reformation. The kingdom became a power center of the Evangelical Lutheran Church but also threw up several important ‘Pietist’ movements in the 18th century that positioned themselves against the formality and rituals of what was in essence the State religion.

Pietists were Lutheran dissidents who reacted against Big Church. They emphasised personal piety and purity, social separation, small worship circles often in houses and often a communal approach to property and wealth.[5] They also expected the second coming of Christ to happen ‘soon’ but had different opinions on where in fact Jesus and his white horse would land. Rapp thought the new country of the United States was the site. Others believed it would be Jerusalem. This group, led by another evangelical leader, J. Lutz, looked eastwards, towards the vast plains of Russia, as a place to move to, since it was quite a bit closer to the Holy Land. Come the Day, they would be able to get to Jerusalem quicker than if they stayed in Germany or moved to Pennsylvania, like the Rappists.

__

Germans, with their reputation as good farmers, were invited by Catherine the Great to move to Russia where she promised them attractive special privileges[6] especially freedom of religion. First settled in the Volga River region, the response was so positive that in 1803 the newly acquired territories of the Crimea and southern Ukraine surrounding the Black Sea were opened up to German and German-speaking settlers. These allotments too quickly filled up with Mennonites, Lutherans and Pietists migrants, a lot from Württemberg, setting up German colonies and villages where they were free to do things in their German way, including speaking German and practicing their own version of Christianity. Germans had over the centuries settled elsewhere in Eastern Europe, including Prussia, Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Soon after Rapp moved to America, another group of Pietist Württembergers headed towards Odessa where a large number of Germans were settled. They settled and moved around the Odessa area for a couple of decades but didn’t always have friendly relations with other settler colonies. In fact, a feature of many German settlements was their physical and social isolation from other villages, especially Russian, Ukrainian, Polish and even other Germans. Economically they were self-sufficient, selling their produce in regional markets and giving birth to smaller ‘colonies’ close to the ‘mother colony’.

In 1819, the Pietists established a colony they named Hoffnungstal (Valley of Hope) near Odessa (Ukraine) but in 1842 moved their colony to what was then Bessarabia and over the next century was to be found on maps as part of Romania, Ukraine and Russia, depending on the political configurations of the time. Germans who had settled in Poland earlier also flowed into this final bit of land set aside for German immigrants. Today the site of Hoffnungstal is in the Ukrainian town of Nadezhdivka, about 20 km south of the Moldovan border.

The unstable political situation naturally made it difficult for lots of Black Sea Germans to identify precisely the country of their birth. Grandpa Rabe’s birthplace in the 1930 Federal Census lists his birthplace as Russia. And that of his father and mother as Germany. Dad wrote in Our Life Together, that his dad had been born in Poland. We know that Grandpa Fritz was born in Hoffnungstal (in Bessarabia, Romania, Ukraine or Russia, take your pick) and that Grandpa Rabe’s mother, Karolina, is listed as being born in Ukraine in 1858.

For what it’s worth, here is my take on our garbled family heritage.

Karolina Schieve (mother of Rudolph Rabe Snr.; grandmother of Dad; my great grandmother) was probably born into a German speaking Lutheran evangelical community settled in the areas around the Black Sea, near Odessa, in 1858. Maybe Hoffnungstal, maybe a similar colony. She married Adolph Schulz whom it seems already had some children, namely Amelia (Mollie), William and Mary all of whom settled in Guelph, North Dakota a tiny, unincorporated village on the plains in the early 20th century. The Schultz’s had lived for some time (if not permanently) in a small town, Lemnitz, not too far from the border with the modern Czech Republic.

Adolph, it seems was a widower and probably quite a bit older than Karolina. One characteristic of the German speaking settlements across Eastern Europe was they moved around a lot. If things weren’t working out in Poland then they would try somewhere else, perhaps around the Black Sea or the Caucasus region. They were double and triple migrants. Maybe Adolph, after the death of his first wife, found himself near Odessa/Bessarabia and married Karolina (or she was compelled to marry him for economic or social reasons; often the case). In any case, Adolph and Karolina had no children together. Perhaps the old (er) man passed away but in February 1885, Karolina married Karl Wilhelm Raabe. She was 27 years old. Raabe was perhaps a couple years older but far closer in age to her than Adolph.

With this liaison, and the entrance into the drama of my Great-Grandfather, Karl Wilhelm Raabe, our family’s deep religious roots once again break the surface. Karl Raabe was born in Leipsig. Not the large, historically famous city and home of Johann Sebastian Bach, Richard Wagner and Richard Schumann. No. But the small German enclave of Leipsig, far away on the eastern steppes of the Ural Mountains and spitting distance from the border with the modern country, Kazakhstan. The bulk of German-speaking immigrants to Imperial Russia had settled in the Volga River basin and around the Black Sea with smaller communities in the northern Caucasus region. But Leipsig, where Great Grandpa Karl was born, was truly ‘in the middle of nowhere’. Podunk, Russia.

Given that social and physical isolation was valued among Pietist/evangelical/non-conformist Christian sects, all the more so they could remain pious as they awaited the second coming of Christ, it’s not stretching it too far to suggest that the Germans in this far outback of Russia, were particularly devout & committed to removing themselves from the world and creating a holy society on earth. Given the small size of the town (never more than a few hundred souls) it seems fair to conclude that the Raabe’s adhered to this strain of spiritual living. Interestingly, the commune of Leipsig was established in 1842, the same year that Hoffnungstal Colony, 3000 kilometers to the south, and from where Karolina and her children emigrated to North Dakota, found its ultimate home in Bessarabia.

Transportation and communication in late 19th century Russia were neither easy nor frequent. But historians have shown that there was considerable movement of Germans across the Russian lands as they sought better opportunities. As many of the communities shared a theology, worldview and lifestyle and came from similar regions back in ‘Germany’[7], it is not at all inconceivable that the Raabe clan way out in the boonies were in touch with the Schieves and or Schultz’s down in Hoffnungstal. Especially when they were searching for suitable mates for their children.

In any case, Karl Wilhelm and Karolina were joined in holy matrimony in February 1885 and enjoyed 15 years of married life together. Edward was born 18 months later in 1886, followed by Wanda (1887), Olga (1890), Julius (1891) with Rudolph, my grandfather, bringing up the rear in 1894. By the time Karolina was 36, she had been married twice and given birth to five children. All on the cold Russian steppes!

__

In 1897, Karl and Karolina and their five young Rabe[8] children were among nearly 2 million Germans living in Russia. They had been drawn by promises of land, non-interference in matters of religion, language and education, exemption from military service and despite the tough environment (blizzards, floods, droughts, armed conflict, hostility from locals) had thrived. Few were outright wealthy but Germans in Russia did enjoy a privileged status. In 1926, 95% of German Russians spoke German at home and few spoke the local languages. We can assume the same about Karl and Karolina.

In the 1870s however, Tsar Alexander II introduced a ‘modernization’ agenda which broadly cancelled all the privileges the Germans had enjoyed for nearly a century. In effect, Germans were now Russian citizens and subject to all the laws and obligations of every other Russian, including military service (6 years upon reaching the age of 20). For Mennonites and other pacifist groups, this presented a crisis. Even if they had no ideological, theological or moral position against military service, few Germans relished sending their sons to war in far away parts of the Empire.

In 1891-92 a major famine (largely man made, as most famines are) ravaged the Volga River basin, and even extended south into Bessarabia, southern Ukraine and even parts of Chelyabinsk region where the Raabe clan had settled in Leipsig.

In 1862, over in the United States, Congress passed the Homestead Act which granted 160 acres of surveyed public land to any adult male who had not borne arms against the American government if they agreed to stay on it for a full five years. Ten years later, in 1872, our dear northern neighbours, the Canadians, enacted the Dominion Lands Act with a similar hope of attracting immigrants to settle their vast prairie lands. And, to ensure America did not encroach on the land and claim it as part of American Territory. Oh, how history repeats itself!

And thus, began another massive wave of German immigration. This time across the oceans to the New World.

In 1874, Germans across Russia began immediately looking for opportunities to move elsewhere. Emissaries were sent from colonies in Bessarabia to investigate migrating to nearby Dobrudscha, in what is now Bulgaria and Romania, and, at the time, a part of the Ottoman Empire. They found it a suitable place to move and left Russia to settle in both existing and newly founded villages. Others migrated to recently opened areas in Central Asia and Siberia, where, although still a part of Russia, there was plenty of land and the laws weren’t strictly enforced yet.[9]

Karl and Karolina must have discussed all these developments as they watched their children grow. In 1900 Karl passed away aged just forty-five leaving Karolina with five young children to manage and take care of. Resilient as she had proven herself to be already, I’m sure the death of Karl increased dramatically her sense of vulnerability and anxiety, especially as Edward her eldest son approached his later teen years. Pretty soon after Karl’s passing Karolina married again, this time to Frederick Kenzle (later Kingsley) who Dad and his siblings referred to Grandpa Fritz. Born in 1860 in Hoffnungstal Colony, it seems possible he and Karolina knew each other at the time they joined forces. Both had children from previous marriages and in 1902 they dispatched Edward Raabe and all three of Fred’s children, Mollie, Mary and William, to North America. To Guelph, North Dakota to be exact. Edward was only 16 but “being happy with what they found America to be, made arrangements for the rest of the family to join them”,[10] which they did the following year, 1903.

Karolina was remembered in her obituary as a ‘good Christian woman’ but I suspect life had caught up with her. 3 marriages. 5 children. Who knows how many significant relocations in ‘Russia’ before arriving in a country where she did not know the language. According to Dad’s memoir, “Fritz Kingsley was a kind man, but unfortunately an alcoholic who at times made life miserable for his family.”

Karolina, the matriarch of the Rudolph Rabe family, passed away in 1908, just fifty years old.

[1] Radical Pietism has been defined by Chauncy David Ensign as ”That branch of the pietisitic movement in Germany, which emphasized separatistic, sectarian and mystical elements”. Quoted in Scott Kisker, Radical Pietism and Early German Methodism: John Seybert and The Evangelical Association, Methodist History, 37:3 (April 1999): 175-188

[2] James Towney, “Divine Economy: George Rapp, The Harmony Society and Jacksonian Democracy” (Masters Thesis, Liberty University, 2014), pg. 6.

[3] 1000-1350 C.E.

[4] Ancestry.com RAPP and Ancestry.com RABE

[5] John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was strongly influenced by the Pietists and adopted the principles of the centrality of the Bible, personal spiritual transformation and spiritual disciplines such as Bible study and devotions.

[6] 1) free transportation to Russia; 2) freedom to settle anywhere in the country; 3) freedom to practice any trade or profession; 4) generous allotments of land to those who chose agriculture; 5) free transportation to the site of settlement; 6) interest-free loans for ten years to establish themselves; 7) freedom from custom duties for property brought in; 9) freedom from taxes for from five to thirty years, depending on the site of the settlement; 9) freedom from custom or excise duties for ten years for those who set up new industries; 10) local self-government for those who established themselves in colonies; 11) full freedom to practice their religion; 12) freedom from military service; 13) all privileges to be applicable to their descendants; 14) freedom to leave if they found Russia unsuitable.

[7] Modern Germany was not established until 1871. Prior to this it was a crazy quilt of independent regional kingdoms, and duchys such as and including, Württemberg.

[8] Raabe, Robey, Robie or Robbie, as per your preference.

[9] Sandy Schilling Payne, “16 June 1871—Tsar Alexander II Revokes German Colonists’ Privileges”, Germans from Russia Settlement Locations (Blog) 16 June 2021

[10] No author credited, “Guelph North Dakota: Granary of the Plains 1883-1983”, Guelph Centennial Committee, 1983, pg. 279