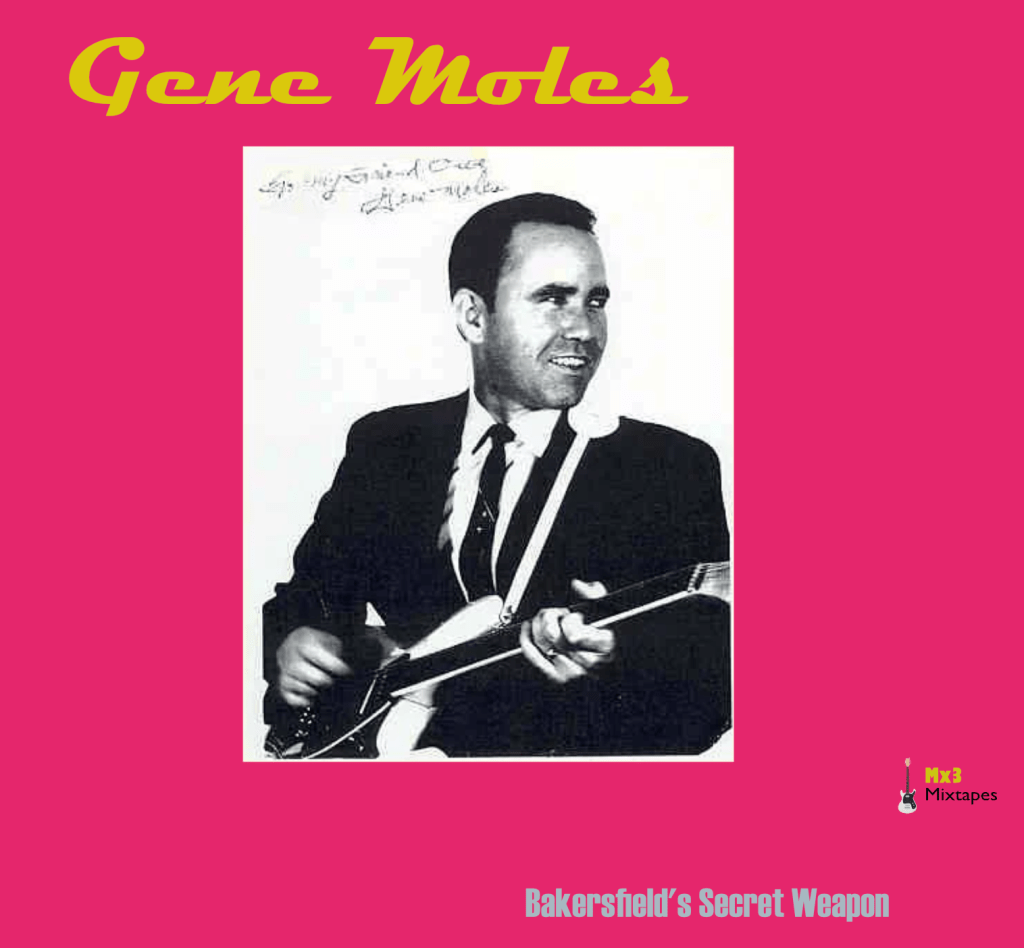

Gene Moles: Bakersfield’s Secret Weapon

True Yarns Vol. 23: songs inspired by real events and people

My Man [Eagles] – Gram Parsons was not really an Eagles fan. He famously blew them off as ‘bubblegum’ just before he passed away in 1973. He didn’t think they were country enough, even though they were being heralded as the ultimate country-rock players, a genre most historians agree Gram Parsons almost single-handedly invented. There was always a tug-of-war in the Eagles, country vs. Rock ‘n’ roll. Eventually, the rocker’s won. The two members of the band with the strongest country music credentials, Randy Meisner and Bernie Leadon, departed after Hotel California and One of These Nights respectively. Leadon had come to the Eagles originally after a short stint in the Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons pioneering band, during which he played on their second album, Burrito Deluxe (1970). My Man was written and sung by Leadon as a tribute to his hero. It was included on their 1974 On the Border album, though it was issued as a single only in the UK.

Malcolm X [The Skatalites] ‘As the nation’s most visible proponent of Black Nationalism, Malcolm X’s challenge to the multiracial, nonviolent approach of Martin Luther King, Jr., helped set the tone for the ideological and tactical conflicts that took place within the black freedom struggle of the 1960s. Given Malcolm X’s abrasive criticism of King and his advocacy of racial separatism, it is not surprising that King rejected the occasional overtures from one of his fiercest critics. However, after Malcolm’s assassination in 1965, King wrote to his widow, Betty Shabazz: “While we did not always see eye to eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt that he had the great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem”.’ Malcolm X was gunned down in February 1965. The Skatalites released this tribute later in the year based upon Sidewinder by jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan released a year previous.

Presidential Rag [Arlo Guthrie] Nice guy Arlo digs the knife into Richard Nixon a few months before he resigned in disgrace. But with lines like, “Nobody elected your family/nobody elected your friends/no one voted your advisers/ and nobody wants the men” this could not be more topical to this current moment.

John Riley [Gráda] An Irish band singing about an Irishman stuck in the San Patricios who fought bravely in the Battle of Churobusco (1847) of the Spanish-American War. “This Mexican unit actually consisted of former American soldiers, mostly Irishmen, who had deserted in the face of anti-Irish sentiments in the old army, and wary of fighting a fellow Catholic nation. The San Patricios had made a name for themselves, fighting from Monterrey, Buena Vista, and Cerro Gordo. Knowing that defeat and capture meant almost certain death for desertion, the San Patricios kept fighting, tearing down the white flag of surrender that other Mexican troops tried to fly. Finally, they were subdued.”

Ode to Olivia [Stella Parton] Dolly’s sister stands up for Olivia Newton-John whose early forays into the American music scene were criticized for not being “real country music”. A debate that will rage till the next meteor wipes us all clean off Earth. “The Country Music Association’s founding premise in 1958 was to keep country music pure; to prevent the infiltration of rock ‘n’ roll. When Olivia won Female Vocalist of the Year in 1974, she raised eyebrows and ruffled feathers. Look at the titleists either side of her winning year: Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Dolly Parton – Nashville Royalty. Olivia remains the only non-American to win the CMA Female Vocalist of the Year. Heads of Nashville convened and formed the Association of Country Entertainers (ACE) in response, to lobby on behalf of traditional country artists. (It fell in a heap when John Denver won Entertainer of the Year the following year and Charlie Rich infamously burned the envelope with Denver’s name in it).” The song is interesting primarily because Dolly was not an Olivia fan at the time. When Stella sang it for her Dolly begged her not to share with Porter Wagoner, her singing partner at the time, apparently because he would freak out!

Vida Blue [Albert Jones] “Vida Blue burst onto the scene in major-league baseball as a fireballing left-hander for the Oakland A’s and served as one of the primary characters in the A’s streak of five division championships and three World Series championships. His career, which spanned from 1969 to 1986, would see high points, including the multiple World Series championships and outstanding pitching performances, as well as dark days, such as his suspension from the game for drug use and his involvement in one of the most publicized contract holdouts in the history of the game. In many ways, the ups and downs of Blue’s baseball career, both on and off of the field, reflected the times during which he played perhaps more than any other of his contemporaries.” Soulman Albert Jones was a Detroit boy and no doubt loved his hometown Tigers but Blue so captured the American imagination in the early 70s a song such as this is a valuable historical milestone. The song was inspired by Vida Blue’s incredible performance in 1971, when he achieved a 24-8 record with a 1.82 ERA, making him the standout player that year.

Lindy Comes to Town [Al Stewart] From Songfacts.com “Charles Lindbergh (1902-74) was an authentic American hero; he rose to fame after making the first nonstop flight from New York to Paris, but suffered personal tragedy when his baby son was kidnapped and murdered, a story that made worldwide headlines; German immigrant Bruno Hauptmann was tried, convicted and executed for the crime. Before the United States entered the Second World War, Lindbergh fought bitterly for the Isolationists, but after it was dragged in by the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, he dusted off his pilot’s wings and joined the conflict in the Pacific. Although Stewart has written many quite detailed biographical songs, this upbeat number focuses solely on Lindbergh’s epic 1927 flight in the Spirit of St Louis, a journey that took 33 1/2 hours and earned him the adulation of millions. It is an antidote to Woody Guthrie’s factually inaccurate “Lindbergh.”

Letter to Linda [Tanya Tucker] A love letter to Linda Ronstadt from Tanya Tucker.

Piney Brown Blues [Big Joe Turner] Written about a real/mythical (?) KC bartender and released in 1955. But a blues singer named Columbus Perry assumed the name Piney Brown in the late 40s and so perhaps this song is inspired by him. Maybe Perry was a bartender too? He did spend time in KC trying to get established before moving East.

Korea Blues [Clifford Blivens & The Johnny Otis Band] The Korean war never ended. And recently the Kim family leader has renounced all efforts and goals to peacefully reunify with the South. Its new chosen path is complete subjugation, by war if necessary. Expect more Blues from Korea in the future.

Ford Econoline [Nancy Griffith] Inspired by the inspiring Rosalie Sorrells, American folk singer of Mormon roots who is way underappreciated. See more about her on the final track of this edition. Of course, the Ford Econoline, “A Workhorse with a Legacy”, has also inspired millions of Americans to haul shit around. When I was 19, we had our eye on one to refurbish and drive down to Mexico. Por supuesto, nunca lo hicimos.

Dixon Ticonderoga [The Carolyn Sills Combo] The combo sings a hymn to a revolutionary innovation of the modern world.

18 Minute Gap [Rue Barclay] Most readers of this blog are of the age when another American Republican President got into trouble for his corrupt ways. Sadly, unlike these days when America is once again Great, Nixon had to pay the price. So unfair. A victim of leftist lunatics and vermin. Want to know what was on those tapes? Want the full story of the tapes and a downloadable version of the 18.35 minutes of nothing? [Editor’s note: that last link is essential reading!]

Simply Spalding Gray [Steve Forbert] Spalding Gray was an iconic New York downtown actor and writer. He is most known for the autobiographical monologues that he wrote and performed for the theatre in the 1980s and 1990s. Theatre critics John Willis and Ben Hodges described his monologue work as “trenchant, personal narratives delivered on sparse, unadorned sets with a dry, WASP, quiet mania.” Gray became famous with his monologue Swimming to Cambodia, which was adapted into a film in 1987 by filmmaker Jonathan Demme. Other one-man shows by Gray that were captured on film include Monster in a Box, directed by Nick Broomfield, and Gray’s Anatomy, directed by Steven Soderbergh. Gray died in New York City, New York, of an apparent suicide in 2004.

Sabra et chatila [Nass el Ghiwane] Another time. Another place. Same shit. The Sabra and Shatila massacre was a massacre of up to 3,500 Palestinian refugees by Israel’s proxy militia, the Phalange, during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. The horrific slaughter prompted outrage and condemnation around the world, with the United Nations General Assembly condemning it as “an act of genocide.” British television called it the Lebanese war’s ‘darkest chapter’.

From Little Things Big Things Grow [Kev Carmody & Paul Kelly] This song has become one of Australia’s informal national anthems. “[P]aying tribute to the Gurindji people, and becoming symbolic of the broader movement for Indigenous equality and land rights in Australia.”

Tennessee Valley Authority [Chatham County Line] The Tennessee Valley Authority act of May 18, 1933, created the Tennessee Valley Authority to oversee the construction of dams to control flooding, improve navigation, and create cheap electric power in the Tennessee Valley basin.

Sunbury 73 [Chris Wilson] The Sunbury Pop Festival was an annual Australian rock music festival held on a 620-acre (2.5 km2) private farm between Sunbury and Diggers Rest, Victoria, which was staged on the Australia Day (26 January) long weekend from 1972 to 1975. Check out Broderick Smith and Carson boogie-ing along as the audience does the usual festival things.

Brigham Young [Rosalie Sorrells] Rosalie Sorrells was one of those American folk artists that insisted on ploughing her own path which was accomplished but largely un(der)recognised. To quote an oft-quoted quote from Elijah Wald, “She traveled around the country while raising five children. She drinks strong men under the table and is the first one up in the morning, bright and cheery and planning one of her famous dinners. And she can make the noisiest barroom crowd shut up and listen when she sings.” See track 12 for Nancy Griffith’s tip of the hat to her. Brigham Young, of course, was the charismatic elder of the Morman Church during its formative pioneering years in Utah. Rosalie was not a Morman but wrote and sang a lot of songs about the community.

City of 1000 Dreams 2

This Love Affair: jazzy vocals Vol. 11

Off and Running: Mx3 Weekly Subscriber-only Mixtape Nr.1

Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

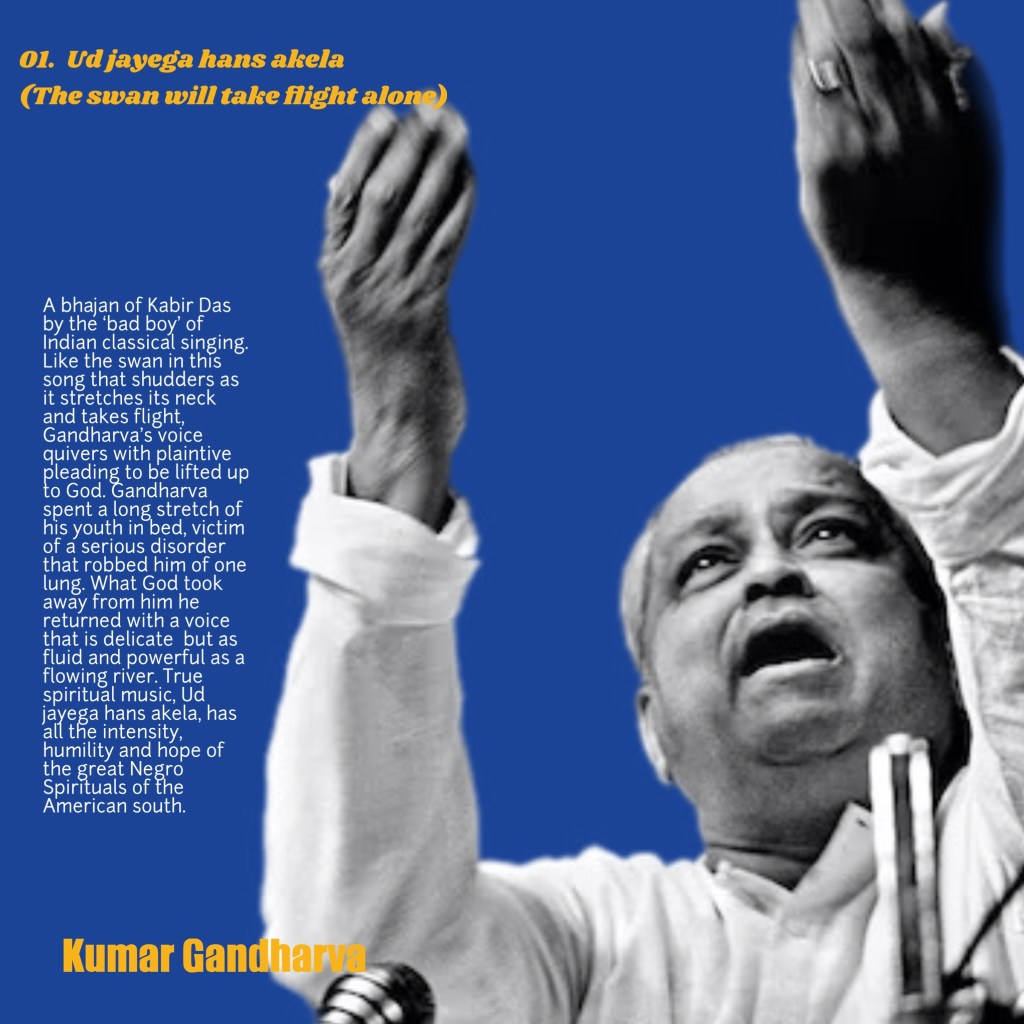

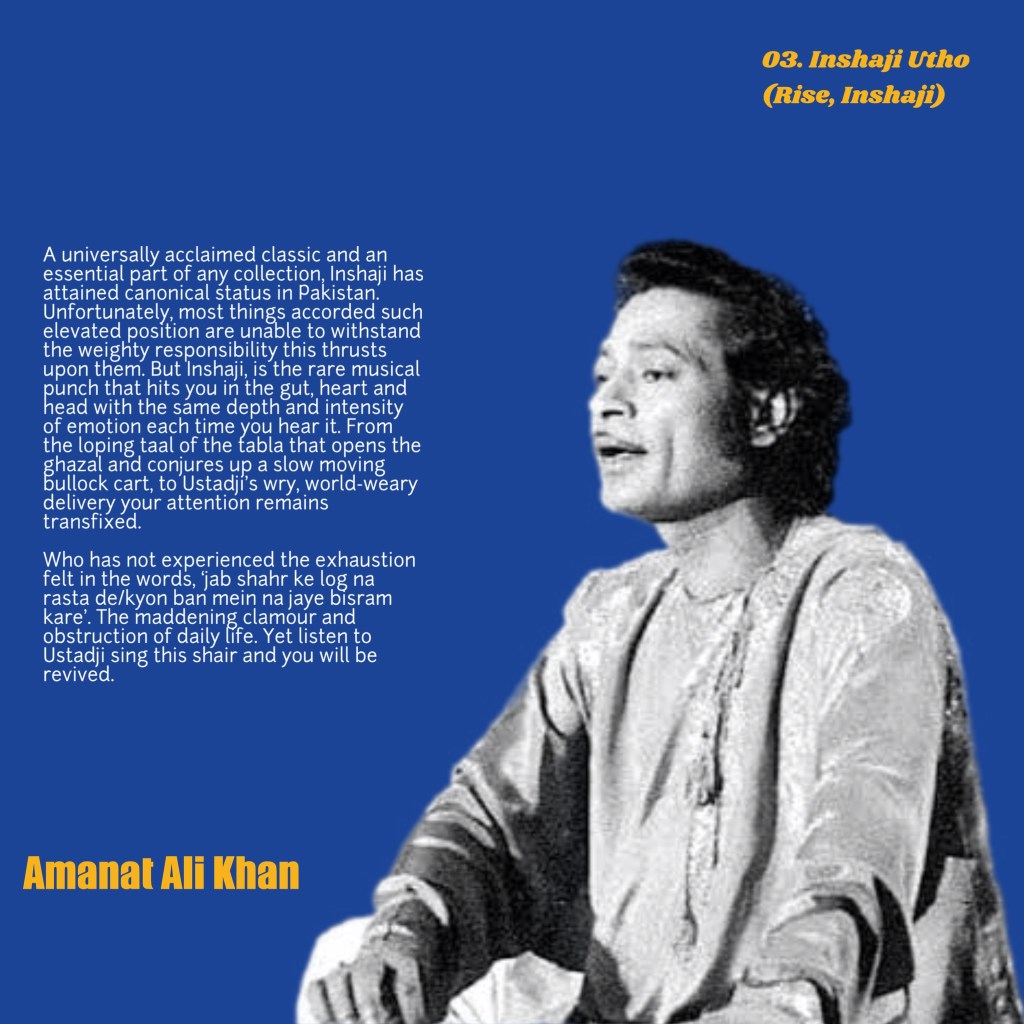

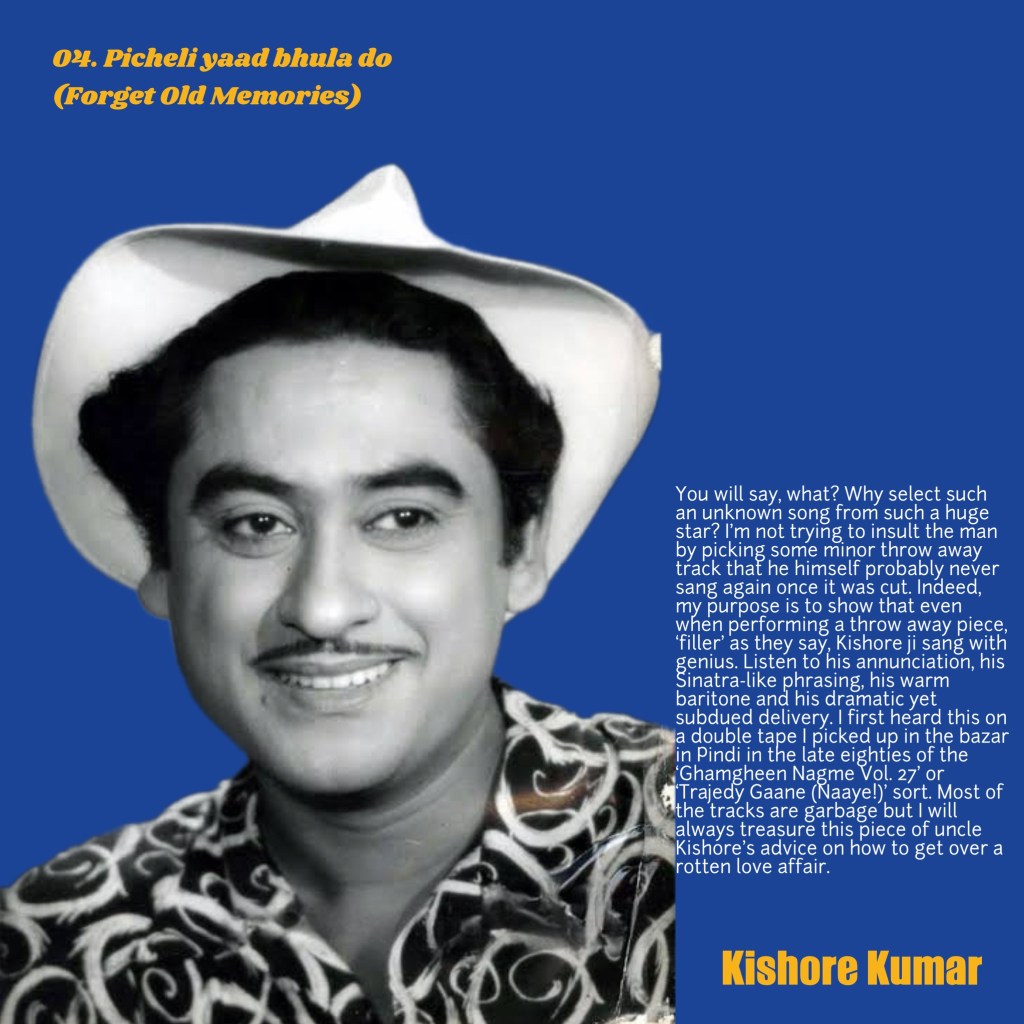

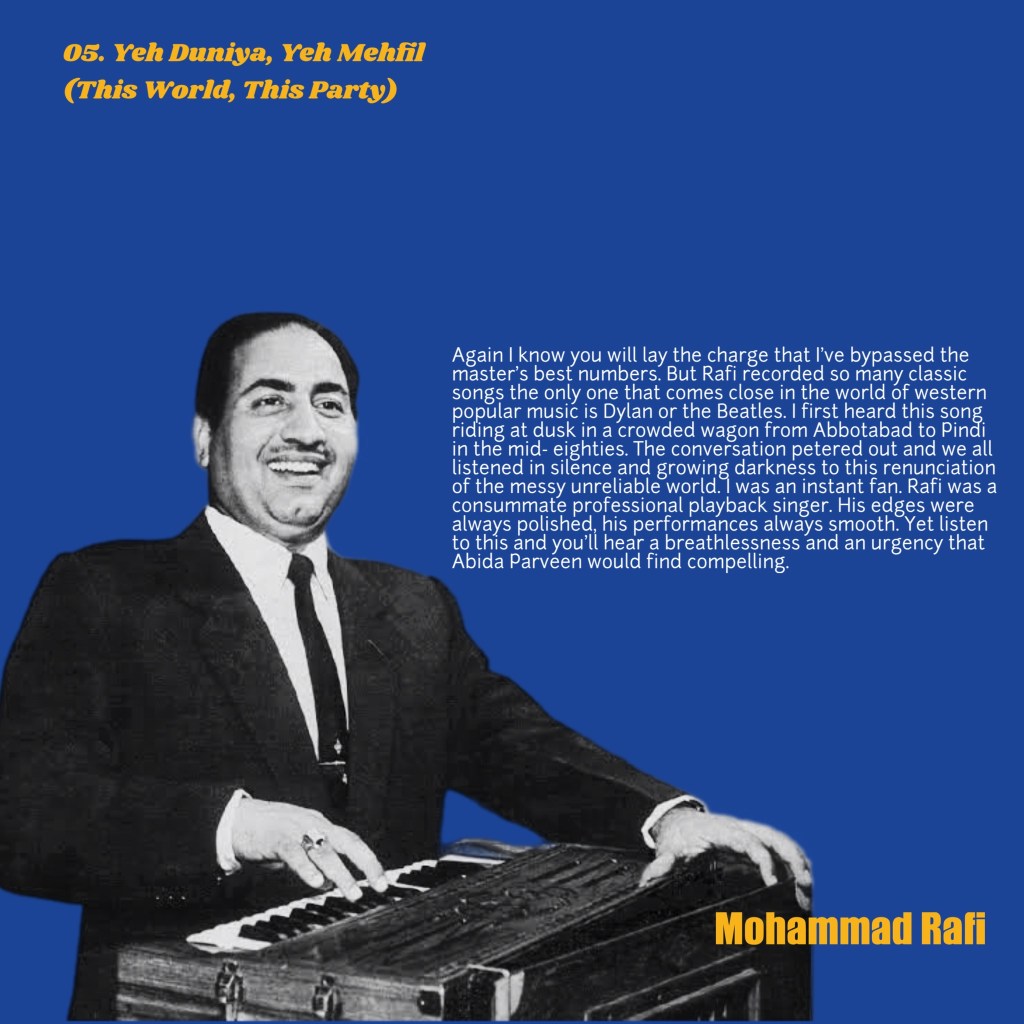

Top Songs from Pakistan and India

Fly Too High: a compendium of Janis Ian

Dylan’s Turn of Phrase

I was lucky to get a pass to a pre-release viewing of A Complete Unknown, the new Dylan biopic, this week. The event included a free drink (which turned out to be a Thatchers Gold Apple Cider in a can, which is so wrong on several levels) and an ‘Australian exclusive’ interview with director James Mangold and leading man, Timothée Chalamet. A great night.

The film itself was very good. I can’t think of another film where an actor captured a character many of us think we know intimately, with near perfection. It was almost as if Dylan himself had morphallactic-ly returned to his early years in the physical form of Chalamet. All the essentials were there. His smirking disdain, his obsessions, his hair, the shades and the voice, bursting at the seams with creativity. A stellar artistic performance by the actor.

[Not to be discounted is Edward Norton as Pete Seeger. His understated performance as Dylan’s early champion is worth the price of a second ticket. The crushing disappointment he conveys when Woody Guthrie makes it clear Dylan is to be his successor, not Pete, is so good.]

The Australian exclusive interview was prerecorded. It featured a local B grade entertainment interviewer who knew little of Dylan’s mystique or music and who received each response from Chalamet with a cooed ‘Ooo, that’s so great!’, more appropriate to an interview with parents of a severely disabled child or a granny fighting back against online scams. Chalamet was pissed and swilled big gulps of vodka straight from the bottle. His answers were disjointed, sometimes coherent. He seemed to be channelling Dylan’s own irritated approach to dumb interviewers. For his part Mangold tried to keep disaster at bay by praising the drunken luvvy next to him and speaking of how they had ‘sculpted’ the performance and their relationship over ‘many years’. O.K.

Definitely go see this film.

As I walked to the cinema, I reflected for the umpteenth time on what it is about Bob Dylan that I love so much. I’m sure I could dig out several dozen reasons but the one that immediately jumped to mind was his ability to turn a phrase. Though I’m a Dylan lifer, there are few if any songs of his that I could recite in their entirety. Maybe Blowing in the Wind if the wind were behind my back. But I can rattle off dozens of phrases that absolutely live within my soul every day.

All I really want to do, is baby be friends with you

It ain’t me babe

He not busy being born is busy dying

She wears an Egyptian ring that sparkles before she speaks

I contain multitudes

Flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark

I used to care, but things have changed

Lincoln Country Road or Armageddon?

A few words, seemingly simply, even thoughtlessly, placed together stand out like sparkling jewels throughout his work. They are adornments. In Indian/Sanskrit aesthetics these are known are ‘alankara’, poetic ornaments or decorations designed to enhance the joy and delight of the reader/listener.

I find myself repeating Dylan’s phrases at random moments and situations. I get a kick out of marrying Dylan’s words with the situations and events of my meagre life. That feeling of delight, according to the ancient Indians, is the entire purpose of poetry, music, art and literature. According to Vijay Kumar Roy, Associate Professor of English, University of Allahabad, “all artists are expected to have a kind of gift, through which imagination can provide the reader [something to] ‘savour’ or ‘relish’, [rasa, in Sanskrit], which is the highest form of joy or supreme bliss (delight). (1)

Sometimes Dylan seems to throw all manner of phrases together, seemingly indifferent to whether they make sense as a whole narrative. For years scholars and fans have tried to unpack and dissect the meaning of each of Dylan’s songs to find a coherent message. Yet if you look at a song like It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) the phrases pile up and it’s hard to draw direct links of meaning between them.

Darkness at the break of noon

Shadows even the silver spoon

The handmade blade, the child’s balloon

Eclipses both the sun and moon

To understand you know too soon

There is no sense in trying

Temptation’s page flies out the door

You follow, find yourself at war

Watch waterfalls of pity roar

You feel to moan but unlike before

You discover that you’d just be one more

Person crying

These verses are full of brilliant lines. Indeed, each line is full of meaning, but you’d be hard put to say exactly what he’s singing about. A simultaneous solar and lunar eclipse? Is the page of temptation a book or a young lad? I’ve seen waterfalls but don’t know what a waterfall of pity is and what that has to do with said page.

But as the song progresses it’s clear Dylan is conjuring a scene of madness, darkness and confusion. He is describing a disjointed disconnected modern society and so there is a certain rasa/taste to this song. Indian aesthetics identify 8 main ‘rasa’ or flavors that an artist may induce in a reader, observer or listener. One of them is Raudra: The Rasa of Anger and Fury which Dylan employs to demonstrate his righteous fury over the state of his country, society and times. It’s a heavy song. It’s got the weight of Jeremiah or Isaiah. But it is decorated and ornamented with the most beautiful turns of phrase.

Darkness at the break of noon

Shadows even the silver spoon

While money doesn’t talk, it swears

You never know how future generations will view yesterday’s heroes but it’s hard to imagine Dylan’s writing being forgotten. His turns of phrase, dozens of them, have entered our daily banter.

The times they are a changing.

Blowing in the wind.

It ain’t me, babe.

You gotta serve somebody

Pick up any of his records, or read his poems/lyrics on line and you’ll discover hundreds of magical delightful phrases that capture the whole gamut of human emotions. But which also mark Dylan as one of the greatest manipulators of words.

Here is one of his phrases I use regularly, in a lot of situations.

A change in the weather is known to be extreme

But what’s the sense of changing horses in midstream?

I’m going out of my mind, oh, oh

With a pain that stops and starts

Like a corkscrew to my heart

Ever since we’ve been apart

(You’re a Big Girl Now, Blood on the Tracks, 1974)

- Roy, Vijay Kumar. 2012. “Indian Aesthetics and the West” In Explorations in Aesthetics, edited by Alka Rastogi. New Delhi: Sarup Book Publishers.

The Night Bus to Tarbela

This photo was taken at the massive Pirwadahi bus station in Rawalpindi. It is from Pirwadahi that long haul buses commence and it is at Pirwadahi that they end their journeys. At least up it was until the early 1990s, when my time in Pakistan came to an end.

I took this photo at my favorite time of day, an hour or so before sunset. It was winter, probably January or February 1989/90 giving the light a warm golden hue. The bus’s windscreen and body had just been washed so the usual dust and streaks of wipers are not a hinderance.

Pakistani bus decorating is one of the country’s great folk arts. What often looks like garish sticker-mania in fact often can be decoded. In this instance starting from the lower left: a religious poster depicting Hazrat Hussain, the Prophet Mohammad’s (PBUH) grandson and spiritual icon to Shi’a Muslims all over the world. The large script at the top of the windscreen is a Q’ranic or other spiritual saying and at the very top you can the words 1988 Model. Signifying the year not of the manufacture of the bus but of the decorations. Multiple stickers of vases and flowers reference one of the most popular design motifs from the Persian world. Scholars find many pre-Islamic references and continuities in such images. In this case, I would imagine the bus’s owner (a Shi’a) has used the stickers merely as pretty decoration, just like the image of the two kittens in the far right lower corner. The open palm stickers, like in many ancient cultures, represent an attitude of blessing and protection as well as invitation. Signaling to the passengers, “Come in, god Bless and protect you on your journey.” As these iron behemoths are not insured, its about as much assurance as you can expect. The calligraphy that balances the Hussain poster notes the destination of the bus, Tarbela Dam, one of Pakistan’s major pieces of infrastructure completed between 1968 and 1976. The pièce de ré·sis·tance is the pair of drapes which can be pulled close when the sun is too bright!

The following piece appeared first on my original blog Washerman’s Dog (17 May 2012). It included a mixtape of music you would be likely to hear on such a trip. The road system in Pakistan has improved immensely since I lived there (’86-’91.) And the music is a bit dated to that era. If you would like to download that mixtape check out the Downloads page.

When I first landed up in Pakistan I was surprised to discover that the way you got around between major cities was not by train, as in India, but by road. Unless your destination was Karachi or Quetta, in which case you flew. And for your road trips you had several choices of transport: bus, Flying Coach or wagon.

Bus: usually a Bedford, gloriously liveried in multiple colours, decorated with beaten tin, twinkling lights, curtains, festooned with flowers (plastic, real and painted) and covered with pithy aphorisms like ‘Maa ki dua/Jannat ki hawa’ (A mother’s prayer is a breeze from heaven). Clientele: general public; those who have more time and less money.

Flying Coach: a no-nonsense and business-like large Mazda or Toyota mini-bus with hydraulic doors that sigh when they open, excellent air conditioning and in most instances reclining seats. Clientele: businessmen, foreign students; those who want to get ‘there’ quick.

Wagon: a Ford van imported from England by Kashmiris. Painted only one colour. Body dented. A few perfunctory invocations of Allah’s blessing on the front. Seats hard. No aircon. Clientele: the slightly better off member of the general public; those with high-risk appetites.

One of the several issues confronting those who choose to travel long distance by road in Pakistan is that the vehicles (with the exception of the Bedford buses) are imported. They can move quite quickly and powerfully, designed as they are for motorways in Japan or UK. The Pakistani highways, alas, are narrow, rutted, poorly lit and crowded. The combination, especially when blended with a driver who is exhausted, just learning his trade or stoned on charas (all three at once, is a permutation I’ve encountered) can give rise to anxiety.

I shall never forget the dear driver (with me in front seat right beside him) who, as we sped into the fast-setting sun that nearly blinded us, decided to change the cassette and light a cigarette at the same time. He did it! And we made it to Gilgit in one piece 12 hours later!

For some reason whenever I found myself on the road it was evening heading into night. Though the hazards increased significantly once the sun went down, I found barreling through the night in some strange way, relaxing and appealing. Probably because there was inevitably a good concert of music to be had. After the first 45 minutes of the journey, most passengers were nodding off or whispering quietly to their companions. The driver would light another cigarette and turn up the cassette and entertain us with a selection of current and evergreen hits.

Inevitably, the concert would include the patron saint of all vehicle drivers, Attaullah Khan Niazi. Indian film music, qawwali and few sharabi ghazals, some folk and other odds and ends like a piece or two from the driver’s home region, often the Northern Areas around Gilgit.

I loved those trips because I was introduced, anonymously, to so much good music.