Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

This brings to a close ‘the background’ story of Lahore. The next sections will deal directly with the movies and movie-making culture of Lahore.

Bahut ghoomi ham ne Dilli aur Indore ki galiyan

Na bhooli hai na bhoolengi Lahore ki galiyan

Yeh Lahore hai Punjab ka dil/Jis zikr par aank chamak uthi hai dil dharak urdthe hain

I’ve roamed the lanes of Delhi and Indore, but I’ve never forgotten nor ever can forget the lanes of Lahore. This is Lahore. The heart of Punjab whose very mention causes the eye to sparkle and the heart to skip a beat

These opening lines of the 1949 Indian film Lahore sum up the deep affection and nostalgic sentiment millions of South Asians feel for the city of Lahore.

**

Lahore, modern Pakistan’s cultural capital, is one of those cities that lives in the very soul and DNA of its residents. Like a handful of other cities across the continents it occupies a place not just on the map but in the imagination of those who know it. It is at once an indivisible part of people’s self-image and something beyond capture. As residents of the city say, Lahore, Lahore hai (Lahore is Lahore). So profound and all encompassing is the city’s essence that the simple acknowledgement of its existence is enough to conjure an entire world.

There’s a small but passionate genre of writing that centres on the city. Novelists, poets, journalists and emigres, displaced at the time of Partition, wax lyrical in their books and gatherings in praise a city they all remember as sophisticated, vibrant, classy, tolerant, full of tasty food, and shady boulevards. Its fabled history and stunning architecture. It’s unique urban culture. If, as they say, nostalgia is a narcotic, then Lahore is one of the subcontinent’s biggest addictions.

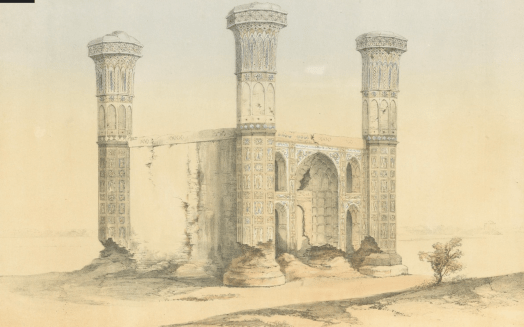

It certainly is an ancient city and the millennia have added a depth of colour and richness that most other cities can only envy. But Lahore has also experienced long periods of cultural and physical devastation when the city’s palaces and shrines were little more than crumbling ruins. When its resplendent gardens lay overgrown and unattended. And it was this sort of Lahore that the East India Company’s redcoats grabbed away from the Sikhs who had ruled Punjab for much of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

After ‘annexing’ Punjab, the British set about rebuilding Lahore. Though the Sikhs, under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, had added some new buildings and gardens to the old city, in general the once glorious imperial city, famous throughout the world for a thousand years, was in an awful state. Amritsar, 80 kms to the east was the Sikh’s spiritual home and a booming commercial hub; Lahore, their world-weary political capital. Important more for what it had once represented—the imperial grandeur and awesome power of the mightiest Empire of the medieval world– than what is now was: a cramped, unhygienic, walled city down on its luck.

At the time the British narcotic-peddling businessmen defeated the Sikhs in February 1849 the suburbs surrounding the old city were little more than ruins. “There is a vast uneven expanse interspersed with the crumbling remains of mosques, tombs and gateways and huge shapeless mounds of rubbish from old brick kilns,” wrote an Englishman who visited the city around this time. Though the Sikh sardars had not gone out of their way to destroy existing Mughal-era buildings they displayed no hesitation in stripping the creamy, jewel-encrusted Makrana marble off the walls of the tombs and palaces to adorn their own havelis.

More than with other cities, the British sensed that in Lahore they had indeed captured a jewel. Milton’s reference to the city in Paradise Lost had been rather cursory. More elaborate and accessible was Thomas Moore’s Orientalist fantasy Lalla Rookh which in the early 19th century had become hugely popular across Europe. Based vaguely around an imagined romance of a Mughal princess in the time of Emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), the poem introduced the name and idea of Shalimar into Western consciousness.

They had now arrived at the splendid city of Lahore whose mausoleums and shrines, magnificent and numberless, where Death appeared to share equal honours with Heaven would have powerfully affected the heart and imagination of Lalla Rookh, if feeling more of this earth had not taken entire possession of her already. She was here met by messengers dispatched from Cashmere who informed her that the King had arrived in the Valley and was himself superintending the sumptuous preparations that were then making in the Saloons of the Shalimar for her reception.

The development of Lahore into one of British India’s premier cities—and a place where a sophisticated industry like movie making could thrive– has to be understood as part of the development of British rule in India. The great riverine plains of Punjab–a stretch of geography that historically included Delhi at the eastern edge and touched the Afghan border in the west–were the last big chunk of agricultural land available in northern India. They marked the final frontier of British India. The Empire’s very existence not to mention the Company’s business model depended on a perpetually growing revenue base collected primarily from raw agricultural products and oppressive taxes on those who worked the land. By the time they reached the Punjab, the Company was the unassailable political and military force in politically fluid landscape. But at the same time, their purely extractive approach to governing had reached its limits too. Beyond Peshawar, a largely Afghan city but in the early 19th century an important Sikh holding, towered the rugged mountains of the Hindu Kush, the historic barrier dividing South from Central Asia. These were a useful security asset but absolutely bereft of economic value.

Soon after wresting control of Punjab the English were confronted with the first substantial resistance to their rule. In 1857 soldiers in the employ of the British East India Company ‘mutinied’ and for over a year engaged their European masters in an armed conflict that engulfed much of north India, saw the destruction of Delhi and the final collapse of the (by this time, entirely symbolic) Mughal Empire. A shocking number–800,000–Indians lost their lives either directly or indirectly as a consequence of the uprising. The European community estimated at around 40,000 in all of India at the time, lost about 6000 people. Though a much smaller number, proportionally it meant that about 1 in every 7 Europeans perished. If it did nothing else, the war exposed the underlying vulnerability and inherent instability of European rule in India. And though they would rule for nearly another century, everything that happened in India after 1857 in some way can be seen as a reaction or delayed response to the conflict.

Though the uprising was ultimately quelled the British were shaken to their core. The East India Company, which over the previous 150 years had demonstrated itself to be little more than a rapacious business enterprise intent on asset stripping the richest country in the world was disbanded by an act of Parliament. India was reconfigured as a Crown Colony under the direct purview of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. The British realised that things had changed. And if they were to continue to benefit from their Indian Empire they would need to experiment with different management techniques including setting up a system that at least appeared to take some interest in good governance rather than simply syphoning off India’s great wealth. One of the immediate, visible signs of the new era was the rise and promotion of the Punjab as a ‘model’ province. A place where the noble intent and attributes of a Pax Britannica could be readily demonstrated and accessible.

Punjab was a vast piece of land but it was by no means uniform. The eastern and to some extent, central districts of Punjab were rich, well-watered agricultural lands with relatively dense populations. The much larger western part of the province spreading out towards the northwest and southwest of Lahore were arid, sparsely populated and agriculturally unproductive lands. In terms of the colonial economy, eastern Punjab was valuable; the west, not so much.

It didn’t take long for the administrators of Punjab to understand that this was unsustainable. It wouldn’t be long before the eastern/central portions of the province would be overpopulated and the land overused. Productivity and more importantly, revenue for the British Exchequer would fall. Also, never far from British minds was the prospect of rising social tensions that an unmet demand for land represented. No one wanted to risk another 1857. Especially not in the land of the fabled Sikhs, who had been consistently lionised by the British as a great “warrior race” and upon whom they were banking to be the backbone of their own security and military apparatus. To use contemporary language they needed to keep the Sikhs sweet.

And so, beginning in the 1880s, with the intention of keeping the Sikhs happy and the Punjab prosperous, the government tilted imperial policy in Punjab toward investment rather than mere extraction. The vast, underutilised and dry western tracts of the province became the focus of a massive economic and social experiment. Construction began on a network of massive canals that diverted water from the Jhelum and Chenab rivers, that by 1920 had turned 10 million acres of ‘formerly desert lands, most of which had been the hitherto uninhabited and worthless property of the Raj’ into some of the richest agricultural land in India. Six districts including the rural areas around Lahore experienced a demographic and economic revolution as hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Hindu and Sikh farmers, were encouraged to move from the eastern parts of Punjab to the west. They settled in new purpose-built towns along the canals to produce wheat and cotton on a scale India had never seen before. And as the biggest city in Punjab (and the largest between Istanbul and Delhi) Lahore itself, the urban hub from which the new Canal Colonies were managed and supported, entered a fresh era of prosperity.

Reimagining Lahore

From the moment the Sikhs were defeated, the British set about rebuilding the crumbling historic city they had inherited. The new administrators were bewildered and not a little intimidated by the old walled city, which they left largely to its own devices. Instead, the English concentrated on the ruins that lay outside the walls. With a fearsome industriousness they cleared the plain to the southeast and laid out a European style suburbia. Christened Donald Town after Donald McLeod, an early Lt. Governor of Punjab, the main thoroughfare in this new part of town was christened McLeod Rd. On either side, a residential and business area for Europeans sprang up including an important and large military base or cantonment, further south in Mian Mir. By the 1930s, the place where McLeod Road crossed Abbott Rd, a junction called Laxmi Chowk, would become (and remains to this day) the central locus of the city’s film industry.

Between 1860 and the early 1900s Lahore found new life as a hugely important regional centre for education, communications, publishing and culture. Delhi, the age-old capital of northern India had been savagely destroyed during the fighting of 1857. The city’s famous tribe of musicians, writers, poets, artists and thinkers fled the capitol in search of more secure places; some headed south to Hyderabad and others east to Lucknow. And with its newly acquired territory in the northwest the British government deliberately identified Lahore as an alternative cultural hub to which they encouraged émigré artists and intellectuals to settle.

Several prominent Urdu language writers and poets did move west to settle in the city where educational institutions were springing up under official sponsorship but also with the investment of wealthy Punjabi landowners and businessmen. Though the city had no real affinity with or history of speaking the Urdu language, a combination of official policy and organic economic development saw Lahore become one of India’s most important Urdu centres. Though the city’s residents continued to speak their beloved Punjabi, using Urdu only for official work or to get a job, Lahore was transformed rather quickly into a bi-lingual town. Their easy facility with both languages and often with English as well, in time would give Punjabis a huge advantage in the nascent Indian film industry.

Lahore’s publishing and printing industry produced newspapers, books, religious texts and magazines in multiple languages including Urdu, English, Persian, Punjabi but also Arabic and Sindhi. The city, already famous for its literary culture, refreshed its traditions with poetry recitations called mushaira which drew poets from across north India as well as significant audiences from the city’s many colleges. By the turn of the century a hundred or more newspapers were available across the Punjab most of which were in Urdu including many published in Lahore, such as Kohinoor, Mitra Vilas and Punjab Samachar. In addition, though catering to a much smaller audience, but widely read and highly regarded were two English dailies, The Tribune and the Civil and Military Gazette, most famous today for it’s most famous resident journalist, Rudyard Kipling.

The number of prominent Urdu writers who were born, educated or settled in Lahore is too vast to mention: Agha Hashr Kashmiri, Taj Imtiaz Taj, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Hali, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishen Chander and of course, in the last years of his life, Sa’adat Hasan Manto many of whom developed a connection with both the local and national film industries.

Northwest India’s educational Mecca

In the late 1830s and 1840s the British laid out the basic parameters of an education policy for India. The ultimate purpose of the policy was very much in keeping with the political agenda of the EIC which was all about control, avoidance of undue investment and efficiency of administration. As such, to the extent that official British efforts were to be focused on educating Indians, it was as a means to advance the Company’s and then Britain’s, commercial and political ends: to create a loyal group of Indian elites who would be conversant in the English language, imbibe European values and culture and be dependent upon Official patronage. In the famous words of William Macaulay a senior and prominent 18th century administrator of the Company, “we must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern.”

And to that end government efforts were to be focused on developing and supporting a system that preferenced higher education as opposed to mass primary education and which was to be delivered entirely in English through institutions modelled on those in Britain, especially the great universities in Oxford and Cambridge.

By the time the final piece of the India puzzle, Punjab, was tapped into place these ideas were fresh in the minds of the English. And so, in keeping with their intent to make the province an exemplar of the colonial project, Lahore was developed into the premier educational city of northwest India. Beginning in the 1860s and continuing up through the first decades of the 20th century, the British supported or sponsored the establishment and development of a number of colleges that became famous as some of the best in India and whose alumni included several generations of elite leaders including multiple Prime Ministers of both Pakistan and India.

Schools like Forman Christian College, founded by an American missionary in 1865, and Government College a year earlier, provided English/Western education to the first generation of Punjabis to live under British rule. These schools were complemented by pioneering medical training colleges (King Edward Medical College) or absorbed into more prominent larger institutions like the University of Punjab in the 1880s. Secondary colleges, especially the world-famous Aitchison College (1864) prepared the young sons of the princes and the landed aristocracy of the Punjab to enter the elite colleges and ultimately, service in the bureaucracy. Being educated in Lahore became almost compulsory if you wanted to pursue a career in business, science, government or the arts. Students came to the city from all across the northwest and in the 1930s Lahore was said to have a student population of nearly 100,000 students enrolled in 270 colleges and schools.

Actor and Hindi movie superstar Dev Anand and his equally talented brothers came to Lahore from Gurdaspur in the east to be educated at Government College, part of the University of Punjab. At the same time, from Rawalpindi further to the northwest, came Balraj Sahni, who established himself as one of India’s finest cinema artists after the Partition. We could fill several pages with the lists of prominent politicians, sportsmen and academics, not to mention military leaders who graduated from Lahore’s elite schools but just a few provide a flavour of the quality of education the city provided. Imran Khan (former Prime Minister of Pakistan and international cricket star), Abdus Salam (1979 Nobel Laureate in Physics), Inder Kumar Gujral (Prime Minister of India), Pervez Musharraf (President and Chief of Army Staff of Pakistan), Allama Mohammad Iqbal (writer and philosopher), Kuldip Nayyar (prominent Indian journalist), Krishen Chander (pioneering Urdu writer), Har Gobind Khorana (1968 Nobel Laureate in Medicine) and Faiz Ahmed Faiz (modern Urdu’s greatest poet).

While Dev Anand and Balraj Sahni were able to attend the elite colleges most of Lahore’s film industry personalities were either educated on the job in the studios and sets or attended a set of schools established to cater to the middle class Hindu and Sikh communities who controlled Lahore’s economy. Schools like DAV College founded by the reformist Arya Samaj educated tens of thousands Hindu and Sikhs. Islamia College, long associated with Allahabad University, offered higher education to Muslims who were a little more sceptical of attending the heavily westernised University of Punjab or Forman Christian College.

The learning environment of Lahore extended to female education as well and the city had a reputation for its relatively progressive attitude towards women participating in public life. Kinnaird College, established by missionaries in 1913 as a counterpart to Forman Christian College, educated the daughters of Punjab’s best and brightest families. Writers Bapsi Sidhwa and Sara Suleri, academics of all disciplines, the human rights lawyer and campaigner, Asma Jehangir and Hindi film actress Kamini Kaushal all graduated from Kinnaird.

Migrants, not only from eastern Punjab but the rest of India came to Lahore to get in on its vibrant economy and cultured society. By the 1920s the city was known not only as a premier destination for higher education but a city of ideas. Hindu reformist movements such as the Arya Samaj and Brahmo Samaj, from Bombay and Calcutta respectively, found fertile ground in Lahore and in the case of the Arya Samaj enjoyed significant growth and popularly in the city.

Political flashpoint

The many educational institutions created an environment in which ideas of all sorts were traded, debated and contested; Lahore slowly gained a reputation as a political hotspot. The British policy of building up a class of loyal Indians ready to fight for the Raj may have been the stated outcome of education in British India but too often things don’t go exactly to plan. With so many students enrolled in hundreds of schools things were bound to get out of control.

In response to the missionaries’ evangelising, each of Punjab’s three major religious groups took upon themselves to reform their own faiths turning Lahore into a site of new self-styled progressive religious teaching. Though founded in Gujarat to the south, Lahore became the main centre of the Arya Samaj, a Hindu reformist group which championed education, women’s participation in public life, a return to Vedic Hinduism as well as an aggressive anti-Muslim, anti-Christian stance. Many of the Hindu middle classes of the city were attracted to its teachings and sent their children to the Samaj’s schools and the influential D.A.V College.

Initially, middle class Sikhs were welcomed and participated in Arya Samaj activities but eventually split from the movment over, among other things, the Samaj’s aggressive campaign of mass reconversion of rural Sikhs to Hinduism. In response, the Sikh community sought to distinguish themselves from the Arya Samaj and began preaching a more exclusive and purist form of Sikhism which focused on the reformation of the government-sponsored ‘clergy’ that controlled Sikh places of worship. The Akali Dal, a group that arose out of activist Sikhs, many from the new Canal colonies, quickly took on an anti-British political agenda which the British promptly labeled as a greater threat to the stability of Punjab and India then Gandhi and the Congress Party. The Sikh Sabha and Akali movement was active across Punjab but especially in Amritsar and Lahore, whose branch was seen as the more radical and political.

Several Muslim communities found themselves developing new identities and leaders too. in the 1930s and 40s, the rural agricultural Muslim communities bounded together with similar rural groups to form a loyal pro-British political coalition. But other groups, such as the Ahrars, established in 1929, articulated a strong anti-British, nationalist and anti-feudal agenda. At the same time, it spearheaded a religious reform agenda that among other things was the first to demand that the small but successful Ahmadiya community be declared non-Muslim.

Though reform and purification of faith were the starting point of all these movements, by the 1920s they had blurred the line between religion and politics. The British kept close tabs on them and openly interfered in their colleges (Khalsa, DAV, Islamia) in an attempt to try to weed out nationalist thought. But it was not to be. The massive economic success of the canal/irrigation projects not only transformed and enriched certain groups but at the same disenfranchised many others, especially the urban middle class Sikhs and Hindus, who were the backbone of Lahore’s economy.

The British state was strong and able to quash most rebellious ideas before they became widespread but in 1907 as a result of a number of pieces of legislation that further pressured and alienated the very population of rural Punjabis that the security of India depended on, violent protests broke out in the Canal Colonies. The cause was championed and given an anti-Raj colour by leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai in Lahore. The British were caught flat footed, and unprepared. Repression and suppression followed quick smart which for a few years seemed to work.

But after WWI Lahore continued to gain a reputation not only for high quality education and culture but as a political hot bed. So much so that its reputation spread far and wide. In 1922 newspaper a rural newspaper in faraway Australia reported “The visit of the Prince of Wales to Lahore, which has been looked forward to with deep anxiety by those responsible for his safety, will, it is believed not be marred by disturbance of any kind. The tension has relaxed in the native city in the past week and it is too much to expect a general attendance of Indians to join the official welcome on Saturday afternoon for Lahore is the notorious centre of political unrest in Northern India but the Prince will not touch even the fringe of the bazars during his four days stay.” (Tweed Daily, Muwrillumbah 25 Feb 1922)

Around that very time T.E. Lawrence (of Arabian fame) was reported to be in Lahore and causing trouble in Afghanistan. Indeed, possibly in the very weeks leading up to Lawrence’s stealthy escape back to England, a young Sikh revolutionary who had been educated in Lahore, Bhagat Singh, assassinated a senior British police official in a case of mistaken identity. Though he escaped and a few months later exploded several smoke bombs while the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi was in session, he allowed himself to be arrested and imprisoned by the Indian government. Using his imprisonment and trial to denounce the Raj, Bhagat Singh became a national cause celebre. Anti-British protests broke out all across India and the chant “Bhagat Singh ke khoon ka asar dekh lena Mitadenga zaalim ka ghar dekh lena” (Wait and see, the effect of Bhagat Singh’s execution: The tyrant’s home will be destroyed, wait and see) became a popular public cry. Though he was hanged in 1931 for his crime, Bhagat Singh’s trial and resistance to colonial oppression made him an exhilarating figure around which the nationalist and Independence movement rallied. Even today he is hailed as a beloved historic martyr across the political spectrum.

Culture and Arts in Colonial Lahore

Intrinsic to Lahore’s self-image is the world of art and culture. It has always been the cultural capital not just of Pakistan but at various times throughout the past, especially during the Mughal period, one of the major cultural centres in all of South Asia.

With the advent of the British, art and art education, like everything else in Indian life, became a project to be moulded into something that served Imperial outcomes. Most British administrators and educationists dismissed Indian art as primitive or bizarre. In the words of John Ruskin, British artist and critic, the only art Indians were capable of was drawing ‘an amalgamation of monstrous objects’. As such, British administrators saw yet another deficit gaping to be filled. In 1875 the Mayo School of Arts, the first such institution outside of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, was established in Lahore. As in education more generally, the purpose of the school was “to initiate the native into new ways of acting and thinking” and of course provide skills that could be put to economic purpose.

John Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard, was appointed as the College’s first principal with a mission to introduce Western drafting and realistic drawing skills to traditional artisans and craftsmen. Kipling himself saw much to admire in Indian art and did what he could to promote it among his colleagues and students, all the while delivering a skills-based, industry-facing curriculum which eventually included the new-fangled medium of photography.

Interestingly, Bhagat Singh, the young political radical had cottoned on to the great potential of photographic images to educate and mobilise the masses against the British. Prior to his arrest and trial, as leader of the radical Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, Singh had used a magic lantern, an early proto-slide projector, in his lectures and political activities. It’s intriguing to consider that perhaps it was a piece of equipment that the Mayo College of Arts had introduced to its students and wider public in Lahore.

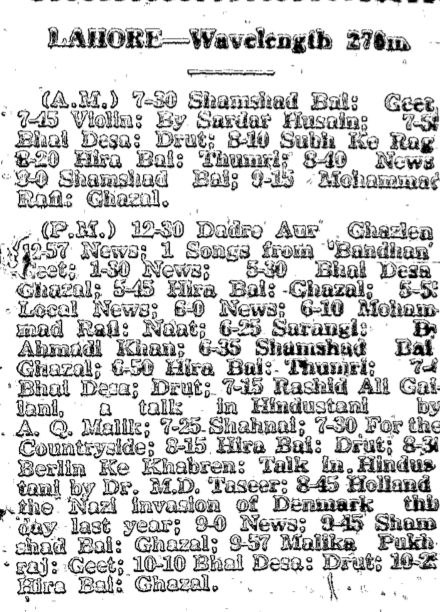

Lahore was a part of the classical music circuit of music conferences which brought a range of classical artists together to perform and compete. The local All India Radio station broadcast live sessions of local residents such as the eminent female singer Roshan Ara Begum and sitarist Ghulam Hussain Khan. And not just classical music. Three years before he broke onto a film scene he was to dominate for the next three and a half decades, in May 1941, a young Mohammad Rafi had a gig singing live on Lahore’s All India Radio station at 9:15 am and again at 6:10 pm.

But it was not just formal art education. Lahore was a city famous for its writers and poets. Its poetry reciting contests, were famous across north India and drew poets, as well as audiences, from far and wide. Music, especially classical music, had a long history of patronage in Lahore. The Bhatti Gate area in the old city, from where some of the earliest film personalities emerged in the early 20th century was renowned for its venerable tradition of classical music. Such luminaries as Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, considered one of the finest voices of modern times, Pandit Amar Nath, and later the brothers Amanat Ali and Fateh Ali Khan of the Patiala gharana, entertained listeners often in their own homes.

Indeed, the city was in love with music. So important a musical centre was Lahore that by the 1930s and 40s several international record companies including Columbia, RCA and HMV had offices in Lahore. The city had been on the talent recording circuit for European companies as early as 1904-5 when two Europeans, William Sinkler Darby and Max Hampe, representatives of Gramophone Records, popped up in Lahore. They made a large number of recordings of women singers, apparently tawaifs (courtesans) who had entertained men for centuries in Lahore’s fabled red light district, Hira Mandi (Diamond Market). In 1906 an ad in a London newspaper read as follows:

Shunker Dass &Co. Nila Gumbaz, Lahore, are prepared to invest a considerable sun, in conjunction with a thoroughly practical firm of makers or factors, to open a Manufactory in India, in order to supply the ever increasing demand for talking machines.

It seems Mr Shunker Dass was unable to generate the capital to set up his talking machine business, as records were known in those early days. But such an ad is evidence of Lahore being on the cultural radar that not only did Mr Dass feel confident to advertise in England but that he had the vision to see an opportunity that was just beginning to emerge when he ad was placed.

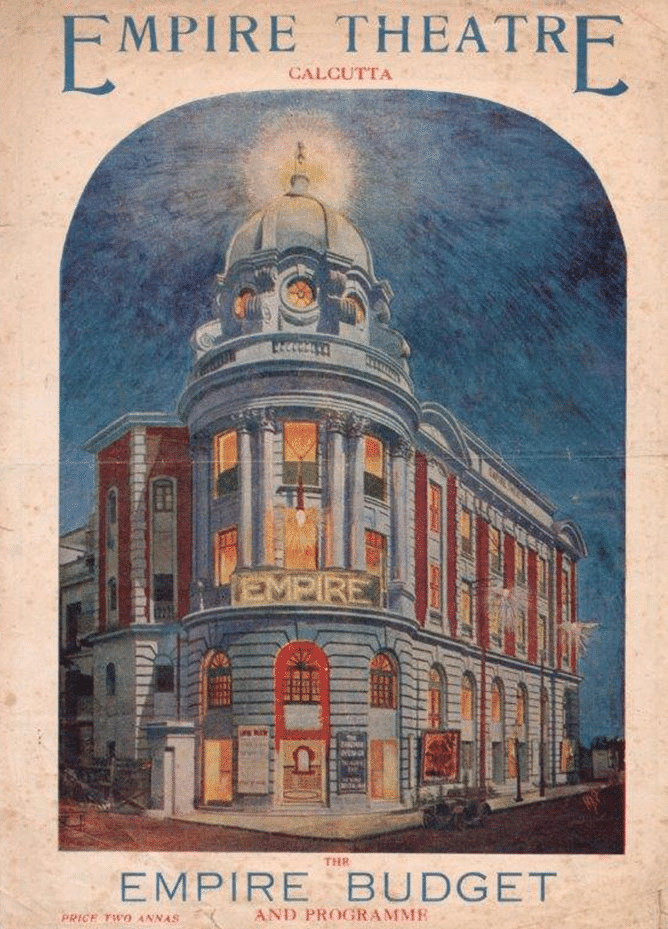

With a sizeable but not overly large population of European and American residents, Lahore attracted performers from around the world and catered to the needs of its non-Indian community. According to the Melbourne Age in January 1947 one of that city’s citizens, a dance instructor by the name of Frank Webber, was on his way to Lahore for a season of dancing at one of the city’s prominent hotels, Falettis. The city regularly hosted travelling dramatic troupes from Europe and America in its theatres not to mention the British community’s love to amateur theatrics which added to the city’s cultural lustre.

Much of the music and poetry and dance took place in and around Hira Mandi, the city’s famous red light district and from whose residents the film industry drew many of its musicians, singers and actresses. During the early days of cinema, actresses who had originally come out of the world of traditional dance, gave recitals to great acclaim and massive audiences before and after their movies.

One local dance troupe the Opera Dancers founded by a Siraj Din from ‘a poor family…passed his matriculation from Punjab University in 1932 and started a troupe to entertain the public with Sarla (a famous danseuse) as his chief artist’. Pran Neville in his book tells of how Miss Sarla drove audiences wild in between shows at local cinema houses

Responding to the loud applause of ‘Mukarar’ (Say it again) from the audience, Sarla advanced gracefully towards the front of the stage. With the burst of a song she turned around with such vigour that the loose folds of her gown expanded and the heavy embroidered border with which it was trimmed fanned out from her waist, showing for an instant the alluring outline of her lower form. She displayed remarkable muscle control and coordination as she worked herself up to reach the climax of her dance. The music went on in waves of tumultuous sound, with the musicians falling more and more under the hypnotic influence of their instruments, crying out ‘Wah Wah-Shabash’ to encourage the dancer. The audience burst out in applause, which manifested itself not only by loud clapping but by the showering of coins onto the stage. The tinkling sound of the coins drove the musicians to a new pitch of enthusiasm just as Miss Sarla made her exit.

Siraj Din and Ms Sarla and the Opera Dancers featured regular shows in Lahore but also entertained Indian and foreign troops during wartime through a special vehicle he called Fauji Dilkhush Sabha (Soldiers Happyheart Association).

V.D. Paluskar and The Gandharva Mahavidyalaya

The story of V.D. Paluskar, one of the most significant figures in modern south Asian cultural history probably illustrates better than any other the sort of city Lahore was in the early part of the 20th century and how many of the necessary elements for a film industry came together in the city. Paluskar himself had only a tenuous relationship with the film world but as an influential cultural figure his ten year sojourn in Lahore is a wonderful window into how the city provided the perfect environment for new cultural ideas.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar was born into a traditional musical family in Maharashtra, western India in 1872. Fired with a deep spiritual need to blend traditional classical music, Hindu devotional practice and education Paluskar was in essence a missionary of sorts. After spending the first 24 or so years of his life as a paid musician in the courts in several small princely states in southern Maharashtra he set out on his own to find a different sort of patron then the small minded autocratic and often musically limited petty royalty his family had been used to serving.

On his travels through western India, Paluskar encountered, at a hilltop shrine, a Hindu ascetic who among other things advised him to head north and to the Punjab in particular. The ascetic instructed him to set up a school in order to live out his destiny. And so the young singer headed north stopping to perform and build his reputation in Gwalior, Delhi, Amritsar and the market center, Okara. In 1898 he made one final move, 130 kilometers NE to Lahore where he began immediately, despite knowing no one or speaking any of the city’s three main languages (Punjabi, Urdu and English), to put together plans for the establishment of a music school.

His choice of Punjab’s capital—now in the midst of rapid development and growth under the British—was unlikely to have been random. Even though he had no connections, the city was well networked and open to exactly the sort of innovative, even revolutionary ideas, Paluskar had banging around in his mind.

To get his idea of a school off the ground he had to raise money and so turned to the middle class Hindu community who were embracing Hindu reform movements like the Arya Samaj which, though founded in Gujarat in Western India, found Lahore to be one of its most important, if not most important site in north India. Arya Samajis were urban and salaried and had both the education and the money as well as the motivation to support causes like Paluskar’s musical-devotionalism. Lahore’s fast developing reputation as a city of education, politics and economic opportunity meant that the the elite and rulers of the many princely states from Baluchistan, Kashmir, and Punjab maintained ties and often residences in the city. Many, especially the maharaja of Kashmir offered Paluskar and his academy, the heavily Sanskritised named Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, critical financial support and patronage.

And though he may not have been conversant in Punjabi or Urdu, Lahore was attracting migrants from all over India. Its economic and strategic rise in importance meant that national vernacular newspapers often had correspondents reporting on events in the city. One such Marathi newspaper, Kesari, began publishing stories about Paluskar’s activities. And though most of his students were local , many were immigrants like himself from Maharashtra including a large number of Parsis who though small in number were prominent as retailers of European goods and services, including owners of Lahore movie halls.

That Lahore and western parts of Punjab were heavily Muslim also had an appeal to the Hindu activist. Paluskar’s entire understanding of north Indian music was that it only could be truly understood and appreciated when performed within the context of a personal Hindu faith. Furthermore, Hindustani classical music, not to mention most of Indian culture, had been debased by Muslims . He believed Muslims performed music only for entertainment and often risque, morally suspect entertainment like courtesan dance recitals, at that.

Paluskar’s vision of a purely Hindu musical world was influential. In nearby Jalandhar where India’s first annual musical festival the Harballabh festival had since 1875 been a place where Punjabi musicians of all creeds and persuasions, but especially Muslim dhrupad artists, performed, Paluskar’s sectarian and vigorously anti-Islamic/anti-Punjabi stanct, made the festival unwelcoming for some of the greatest Muslim classical musicians of the era.

Though Paluskar’s vision and mission could be interpreted as being conservative and traditionalist in that it sought to reclaim the north Indian music system from Muslims and restore it to its rightful place as part of true Hindu faith and practice, (however, contentious that position was/is) there were several elements that should be seen as radical. The most important being his musical notation system. North Indian classical music has traditionally been an oral tradition; Paluskar himself never received formal training and his own teacher never even shared with him the names of the ragas he was learning. It was a secretive and territorial business with performers and gharanas fiercely committed to protecting their styles, innovations and knowledge. This was done through a guru to whom a student devoted his life and fulfilled the role of servant until he was accomplished enough —after many years—to take on his own students. Unlike in Western music, no music notations had ever been committed to writing.

Paluskar’s musical notation system, which he had begun to put down on paper while living for some months in Okara, became of his first projects upon arriving in Lahore. With the support of Hindu supporters, Paluskar was to publish the system which formed a fundamental part of the curriculum of his school.

The Gandharava Mahavidhalaya became another of Lahore’s many and varied educational institutions. It offered a rigorous traditional 9 year (!) course of intense training but also shorter teacher training courses called updeshak, for poor students. The school also actively recruited middle class women, revolutionary step for the time. Paluskar not only used the press to promote his work but tapped into the booming printing industry of Lahore to publish short instructional texts in pamphlet form on various instruments and music themes.

His student body grew and included a relatively large number of women and especially Parsi women but also Maharashtrians who had migrated to the city. Within several years his school was well established and financially sound but Paluskar still felt he needed a higher national profile if he was to really have an impact. Once again, Lahore, his adopted city, was able to provide the opportunity.

In 1906 a ‘durbar’—a public ceremony to honour the visit of royalty—was organised to mark the birth of King George V’s son. Paluskar recognised that if he could get on the program as part of the entertainment the eyes and ears of the entire country would be upon him. Through his own Lahori and royal connections he was able to secure a 15 minute slot which he used to promote his vision and school even further. By 1907/8 his school was not only well established but the Paluskar name as a educationist, a Hindu cultural reformer, an innovator and as an accomplished singer in his own right was secure. Though he left Lahore to return to Bombay in 1908 where he set up another branch of the GMV, Lahore was the city in which, as the sadhu had predicted, he would meet his destiny. The GMV in Lahore continued to operate until 1947 and the Partition when it’s heavily Hinduised curricullum and patronage became unviable.

Several of Lahore’s greatest musical names such as Pandit Amar Nath had associations with the GMV either as students or instructors and throughout the 1940s contributed musical scores for Lahore’s film industry. Paluskar himself probably felt films were exactly the sort of entertainment classical music should NOT be associated with but before his death in 1955, his son, D.V., performed in two films, the most famous of which, Baiju Bawra, he surprisingly performed a duet with the Muslim vocal maestro Amir Khan!

Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

Mughal Stories

From day to day, experts present books to the emperor who hears every book from beginning to end. Every day he marks the spot where they have reached with his pearl-strewing pen. He does not tire of hearing a book again and again, but listens with great interest. The Akhlaq-i-Nasiri by Tusi, the Kimiya-yi-sa’adat by Ghazzali, the Gulistan by Sa’di, the Masnavi-i-ma’navi by Rumi, the Shahnama by Firdausi, the khamsa of Shaikh Nizami, the kulliyats of Amir Khusrau and Maula Jami, the divans of Khaqani, Anvari and other history books are read out to him. He rewards the readers with gold and silver according to the number of pages read.

It was between the 9th and 19th centuries when north India was ruled by a series of Muslim sultans that Lahore reached its cultural apogee. And especially under the Mughals who built India into the medieval world’s grandest empire. Akbar, the greatest of all the Mughal emperors of India loved books and stories. The snippet above, from his biographer Abul Fazl, is a fascinating glimpse into the cultured atmosphere that permeated the courts of the ruling elite of northern India. The royal library, Abul Fazl proudly noted, included books written in Hindavi (early Hindustani), Greek, Persian, Arabic and Kashmiri. Akbar’s sons and grandsons and many of his senior nobles continued to add to the library, composing their own works but also drawing to the great darbar (court) of Lahore the greatest talents from all across India, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and even as far away as Iraq.

The Mughals looked to Persia for their notions of culture and gave pride of place not just to the Persian language but to the great poets and thinkers of Iran. And it was from Persia that many of the grand stories they loved so much and which they adopted and were absorbed into Indian culture first came. The elites of northern Indian during this period adopted a number of Persian poetic and literary forms in which they preserved their histories, but also stories, poems and philosophies.

Several of these forms, especially the qasida, which was a poem in praise of the monarch, remained a novelty of the darbar and did not influence broader society, but several others did. Chief among these was the qissa, an extended poem that combined elements of moral and linguistic instruction as well as entertainment. The subject matter were stories of military valour, spiritual attainment, love and romance. The Mughals, especially Akbar and his son Jahangir enjoyed the qissa Dastan-i-Amir Hamza which relates at great length and with vivid imagination the fantastic adventures of the Prophet Mohammad’s uncle Hamza. So much did Akbar appreciate this work that he commissioned a massive project to illustrate the entire epic. Completed over a period of 14 years (1562-77) the final product included 1400 full page miniature paintings and was housed in 14 volumes.

Qissas were not just stories but in the control of a good narrator, complete one-man performances/ shows. Some of the royal qissa-khawans (story tellers) are recorded as demonstrating all manner of expressions, body movements and vocal tones in their telling, sometimes even transforming themselves, in the words of one critic of Lucknow, into tasvirs (pictures). Thus, introducing for the first time into Lahore the concept of moving pictures! Akbar so loved the story that several times he is described as telling and acting out the qissa himself in front of courtiers and guests. When Delhi was sacked by the Afghan Nadir Shah in 1739 the reigning emperor Muhammad Shah pleaded that after the peacock throne what he most desired to be returned to him was Akbar’s Hamzanama which had illustrations ‘beyond imagination’.

The critics of the day stressed both telling and listening to stories were beneficial to the soul with some claiming that in the cosmic order of beings, poets and storytellers were ranked second, right behind Prophets and before Emperors! Though this is undoubtedly a minority view, the best qissa-khawans were indeed highly esteemed.

In 1617, Emperor Jahangir, son of Akbar the Great, recorded the following event:

Mulla Asad the storyteller, one of the servants of Mirza Ghazi, came in those same days from Thatta and waited on me. Since he was skilled in transmitted accounts and sweet tales, and was good in his expression, I was struck with his company, and made him happy with the title of Mahzuz Khan. I gave him 1000 rupees, a robe of honor, a horse, an elephant in chains, and a palanquin. After a few days I gave the order for him to be weighed against rupees, and his weight came up to 4,400 rupees. He was honored with a mansab of 200 persons, and 20 horse. I ordered that he should always be present at the gatherings for a chat [gap].

It was under the reign, and patronage of Jahangir that Lahore became the favoured city of the Mughals. The emperor is remembered for ruling over a stable and prosperous Empire and for patronizing painting, poetry and architecture. A man of artistic inclinations it was during this time that story forms like masnavi which told of current events and wonderful victories and ghazal a short romantic-mystical form of poetry superseded other forms of literature. The ghazal in particular was championed by Jahangir and his son and successor, Shahjahan.

The ghazal both facilitated a large appreciation of poetry outside the circles of the aristocracy, among people of all walks of life, and began to be composed and recited in all sorts of settings including by women, in private homes, in public houses and in competitions. The masnavi quickly declined because compared to the ghazal it was a bit lengthy and rather tedious. The ghazal on the other hand, was snappy, called for clever word play and rarely ran more than a few verses. Mushaira, poetry recitations that centred around the ghazal, became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Lahore during this period.

Many tales are told of courtly mushaira presided over by the Emperor who believed that when expertly delivered, a ghazal was full of magical power.

One night a singer by the name of Sayyid Shah was performing for the Emperor and impersonated an ecstatic state (sama). Jahangir questioned the meaning of one line from the ghazal

Every community has its right way, creed and prayer

I turn to pray towards him with his cap awry

From the audience the royal seal engraver, one Mulla Ali gave an explanation of the line which was written by Amir Khusrau and which his father had taught him. As soon as he finished telling the story, Mulla Ali collapsed and despite the best efforts of the royal physicians to revive him, passed away.

Of course, this literary world of elaborate illustrated tomes, royal qisse and the like was not uniquely Punjabi. Rather it was the literary province of the elite and as such, familiar to most urban literate North Indians. But the mass of people was not literate and had no access to the libraries, the texts, treatises and poets of the nobility. And yet beyond the forts and palaces and even beyond the urban areas of Mughal India there pulsated a great tradition of storytelling that influenced the emergence of films in the early 20th century.

To name all of the genres of Punjabi storytelling would be nearly impossible. In addition to qissa and ghazal there were afsane (stories), dastan (heroic tales), latifa (jokes), katha (Puranic stories), naat (poetry in praise of the Prophet), kafi (sufi poems), boliyan (musical couplets sung by women), dhadhi, kirtan, bhajan, swang, sangit, nautanki , marsiya, mo’jizat kahanis (miracle stories of Shi’a Muslims), mahavara (proverbs) and so on.

These forms of storytelling were a part of everyday life for the people of Lahore and the Punjab. Though they may never have seen the beautiful courtly books produced by the Emperors, the characters, plotlines and themes were deeply embedded in the consciousness and culture of common folk.

One story in particular, Heer Ranjha, based on the Arabic classic Laila Majnun, was especially beloved by Punjabis. Compiled originally in the time of Akbar by a storyteller named Damodar Gulati, Heer Ranjha tells the story of a beautiful girl, Heer, who is wooed by a flute-playing handsome young man Ranjha. Rejected by Heer’s family because he belongs to a rival Punjabi clan, Ranjha turns toward a spiritual path. He spends time in Tilla Jogian, the premier centre of Hindu ascetism in the medieval period, and becomes a powerful kanpatha (pierced ear) jogi. His identity is uncovered by Heer’s friends who convince her to run away with him which ends badly with the death of both lovers.

The tale is the greatest of the many similar legends known as tragic love stories, the speciality of Punjab. Sohni Mahiwal, Sassi Pannu and Dhola Bhatti are taken from the same tradition and have been told, acted and sung to rapt audiences for centuries. Stories such as these and others, like Anarkali, whether recorded in royal tomes or told under a tree by a wondering minstrel formed the foundational inspiration for Lahore’s movie makers. By 1932, just four years after the Lahore produced its first film, Heer Ranjha had already been made into a movie four times!

Performing Arts

Though the earliest Punjabi stories were written down during the Indus Valley civilization, once Harappa and the other cities were abandoned, India would not use writing again until the rule of the emperor Asoka, more than 1500 years later.

The Vedas were memorised and passed on word for word from generation to generation through a caste of priests, the Brahmins. And though many of the later Buddhist tales and eventually, even the Mahabharata and Ramayana were put into written form, writing, reading and access to these skills were confined to the very thinnest layer of elite society. The stories of Punjab survived because they were remembered, retold, performed on stages, recited in poems, acted out in the streets and reimagined with each generation. This oral and physical transmission, this retelling and telling again, kept the stories fresh and alive, changing, not only depending on who was doing the dancing or singing but whether the context was spiritual, secular, public or private.

As with its oral and written literature, Punjab is likewise blessed with a huge variety of musical styles and musician groups. Broadly referred to by the public as mirasi, the society of hereditary Punjabi musicians is complex, and highly differentiated. Though musicians, singers and dancers were uniformly relegated to the outer limits of the caste and class system they played an important, even essential role in Punjabi society. They were the repositories of significant parts of family, folk, clan culture and history. When the movies arrived, the mirasi provided many of the musicians, dancers, singers and composers of what more than any other single trait exemplifies Pakistani/Indian popular movies, the song.

Certain groups of singers have had a direct and enduring connection with the film industry. The dhadhis, wandering minstrels and balladeers who trace their lineage back to the times of Akbar the Great, were particularly active in Punjab. Accompanying themselves on an hourglass-shaped hand drum (dhadh) and a variety of bowed instruments, dhadis specialised in singing heroic tales (var) of local chieftains, especially Sikh rajas ,as well as the tragic love tales such as Heer Ranjha and Sohni Mahiwal. Qawwals, who are sometimes considered part of the dhadhi tradition, were associated with the Sufi shrines and sing an intense trance (sama) inducing music that is so identified with South Asian Islamic practice. Qawwali was a form that was quickly picked up by film makers who inserted it into scenes as light relief or as a sonic representation of an Islamic character or theme.

Also associated with spiritual singing were a class of Muslim singers known as rubabis (after the Afghan stringed lute, rubab). The Sikh gurus employed rubabis to sing kirtans and shabad, essentially the sayings of the various Sikh gurus sung in their temples (gurdwara) as part of Sikh worship. These musicians had respected musical pedigrees and were expert on the rubab, harmonium, drums and other instruments. Being largely a Muslim group, most moved to Pakistan after 1947 and several played critical, pioneering roles as musical directors in the film world that grew up in Lahore.

The brass wedding bands that became an urban phenomenon in north India in the 19th century drew their members from yet another group of hereditary musicians known variously as Mazhabi (if they were Sikh), Musalli (if they were Muslim) and Valmiki (if they were Hindu). These musicians provided services including acting as town criers and news readers. They would make community announcements while beating their drums and playing their horns and clarinets. During festivals and celebrations they entertained people from their vast repertoire of religious and secular songs. As the forms of entertainment changed in the 20th century and especially when sound and music were incorporated into movies in the 1930s, these skilled players formed the backbone of the studio orchestras that produced the amazing soundtracks of the films.

In addition to singers and musicians a universe of street performers, actors and magicians made up part of the Punjabi landscape as well. There were bazigaars (acrobats and contortionists who also sang and acted), bhands (comics) who interrupted weddings and other events to make fun of prominent members of the family and their guests with quick jokes and bawdy repartee for small sums, madaars (jugglers and magicians) who with their magical powders and wands would make birds, eggs and even people disappear and reappear at will.

These groups performed publicly on the streets, in city squares or open fields and bazaars. At any fair (mela) or ‘urs’ (sufi celebration at a shrine) all of these and more would be part of the entertainment. Indian diplomat, Pran Neville, writes in his memoir of Lahore, “we had but to walk into the streets to be entertained by one or the other professional jugglers, madaris (magicians), baazigars (acrobats), bhands (jesters), animal and bird tamers, snake charmers, singers, not to mention the Chinese performers of gymnastic feats who would be out on their daily rounds.”[1] Like the mirasi, many of these castes of public entertainers found that the new film studios popping up in Lahore could be an unexpected source of livelihood.

If Parsi Theatre inspired the early film makers of Bombay, in Punjab other forms of theatre were just as important: swang, naqqali and nautanki. Each of these theatrical codes were common across the Punjabi countryside where performing troupes travelled and performed a rich variety of dramas.

The most important of the traditional theatres in Punjab was a form of nautanki known locally as swang. In essence swang which takes its name from the Sanskrit word for music (sangit) is informal folk opera. The production incorporates liberal portions of singing and dance and often all the parts are sung rather than spoken.

A performance would generally take place in an open part of a village where a local dignitary had invited the troupe to play. After a day of preparation during which the excitement built as stages were erected and children ran amok amidst the activity. The performers prepared by singing for hours with the heads facing downwards into the village’s wells, a practice that allowed them to improve their range and enhance their projection. The actual performance would finally begin late in the evening and continue till the early hours of the morning. If the plot was a long one this would continue over a number of evenings.

Audience participation–hissing, shouting, calling out requests for songs or jokes to be repeated–was expected and happily accommodated. The performers were masterful singers who had to project their voices over the audience noise and often compete against a rival troupe performing in another part of the village. It was said that some of the best singers could be heard more than a mile away. One only needs to listen to the resounding voice of Noor Jehan, Pakistan’s Queen of Melody, and one of the greatest film singers of the subcontinent, to get a sense of the amazing power of these traditional singers.

Long before Nargis played Radha in Mother India (1957) or Prithviraj Kapoor played Akbar in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) these open-air travelling opera companies were laying the essential template of and sketching out the iconic roles for South Asian popular cinema.

The City as a Story

Lahore, the cultural capital of the greater Punjab region was itself was a city of a million tales. In many ways Lahore, a city so fabled for so long, was the most famous of Punjab’s myriad stories.

The origins of Lahore stretch back to one of the two foundational epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana. In a storyline familiar to all movie lovers in South Asia, we are told that Sita, Rama’s wife and a goddess in her own right, becomes pregnant making her jealous husband, Rama, question her fidelity. Falsely accusing her of adultery, Rama turns Sita out of the house. Deep in a forest Sita gives birth to twin boys, Lav and Kush, whom she raises with great love and devotion. In a dramatic twist of Fate, years later, the boys are reunited with their father whom they have never met. They take him into the forest to meet their mother. Ram is stunned and realises his mistake but despite Rama’s protestations and desperate apologies, Sita is swallowed up by the earth and returned to the Heavens. Rama goes on to rule his kingdom with his two sons by his side in a Golden Era of peace and stability. When the time comes, he sets Lav and Kush up in the far West of his country where they establish themselves in two cities. Kush in Kasur, 52 km southeast of Lahore on the Indian border, and Lav in Lavapuri, modern Lahore, where even today, inside the fort of Lahore, there is still a small temple dedicated to this son of Lord Rama.

Despite its hoary Hindu roots, and being described as early as 300 BCE by the Greek historian Megasthenes as a place ‘of great culture and charm’, Lahore’s greatest glory was experienced when it was the capital of various Muslim sultanates and states. Throughout the medieval period when northern India was ruled by a succession of ethnic Turkish rulers who promoted a heavily Persianised culture, Lahore was a city of prime strategic, commercial and cultural significance. And despite its oppressive summer heat a reputation of luxury, elegance and sophistication attached to the city. Its guilds and craftsmen were heralded throughout the region and beyond; its poets, some of the most beloved, even in Persia. Like a handful of other cities around the world—modern Paris and New York for example—Lahore has developed a special atmosphere which has caused both natives and visitors to fall in love with it. Way back in the 12th century, Masud ibn Said al Salman one of the city’s most popular poets found himself imprisoned far from his home city for pissing off one of the city’s rulers. Pining away in his cell he wrote a lamentation.

Lahore my love… How are you?

Without your radiant sun, oh How are you?

Your darling child was torn away from you

With sighs, laments and cries, woe! How are you?

Each of the four great Mughals (Akbar, Jahangir, Shahjahan and Aurangzeb) did their bit to build, extend and refurbish the city. Along with Agra and Delhi and for a while Fatehpur Sikri, Lahore served for years at a time as the Imperial capital and was heavily fortified as a military hub. As it enjoyed the presence of the Emperor himself, artists, administrators, philosophers and emissaries hailing from all across the world came to Lahore to live, seek patronage and practice their speciality.

Poets such as ‘Urfi’ of Iran made Lahore their home finding the relatively tolerant and inclusive atmosphere a delicious change from the claustrophobic Shi’a Islam of his home country. He and other poets employed by the durbar [court] produced sublime poems which were sometimes reproduced on paper reputed to be as delicate and as thin as butterfly wings. Artisans brought their skills and looms to the royal city which by the 16th century had an international reputation for producing exquisite silken carpets which, in the words of one historian, made “the carpets made at Kirman in the manufactory of the kings of Iran, look like coarse” rugs.

The painters who made Lahore their home—both immigrants from Iran and the hills of Punjab and Kashmir, as well as natives—brought glory and awe to the city and its rulers. Ibrahim Lahori and Kalu Lahori, two painters in the court of Akbar illustrated a book called Darabnama (The Story of Darab) which set out the exploits of the young Akbar, sometimes in fantastic detail, just after he had decided to leave his new purpose-built capital, Fatehpur Sikri, to take up residence in Lahore. Their miniatures brought to life the Persian text which told wild tales of dragons swallowing both horses and their riders in one awesome gulp, as well as radical illustrations of naked humans which according to art historians were never before so accurately depicted by Indian artists. The Darabnama which is recorded as being one of the emperor’s favourite story books also depicts scenes from courtly life such as Akbar being praised and honoured by rulers from other parts of the world and India. Ibrahim Lahori along with miniaturists like Madhu Khurd are credited with bringing a fresh and naturalistic realism to portraiture. It was in Lahore-produced books like the Darabnama that for the first time individuals with all their physical quirks—bulging pot bellies, monobrows, turban styles—could be identified as real historical individuals.

The city’s countless mosques and Sufi dargah (tombs) honouring Lahore’s many saints and pirs are not just revered places of devotion but subjects of and characters in stories filled with miracles and magic that are still told today. The city’s storied inner walled city dominated by the domes of the Jam’a masjid but filled with hundreds of other havelis (mansions), shrines, tombs, pleasure palaces and gardens are themselves characters in the various storylines. How many poems, songs, operas and movies, including made in Hollywood, include the name Shalimar—those famous Mughal-era gardens of Lahore?

Probably the most famous of Lahore’s many stories and one that has been retold in film in both Pakistan and India many times, is that of Anarkali. Like all tales that have been passed down through generations this one has several different tellings but the most famous and popular one is the tragic one.

One day a Persian trader came to Lahore for business and brought with him members of his family. In his caravan was his beautiful pink complexioned daughter Nadira also known as Sharf un-Nissa. Her beauty stunned the bazaars of Lahore and word quickly reached the Emperor himself that there was a woman as splendidly gorgeous as a pomegranate seed in his city. He summoned the merchant to his court and upon seeing the young woman fell immediately in love with her graceful charm. The young woman’s father was only too pleased to accede to the great Mughal’s request for Nadira to be allowed to join the royal harem.

Much to the chagrin of his wives and other concubines Akbar seemed completely fixated upon the beautiful Iranian girl who was rechristened Anarkali (pomegranate seed) by the King himself. The only time she was not by his side was when he was away from Lahore, conquering yet more lands and expanding the glory of his family and empire. And so it happened when Akbar was leading his armies in a campaign in central India, Anarkali and the crown prince, Salim, later to rule as Jahangir, developed an intimate relationship. The gossip hit the bazaars and everyone spoke of how much the two loved each other. Salim it was said was ready even to renounce his right to the throne of India for a life with Anarkali.

When Akbar returned to Lahore he called for Anarkali but immediately sensed something different in the way she approached him. ‘What is the matter,’ he cooed but she resisted his embrace and made an excuse to retire to her chambers as swiftly as possible. Akbar was upset and soon livid when his spies and courtiers informed him of the fool Anarkali had made of him during his absence. ‘The bazaar is echoing with jokes that say Your Highness is too old to water such a lovely tree as Anakali’.

The next day Anarkali was summoned to the Emperor’s chambers. ‘Is what I am told true? That you love Salim more than me?’

Anarkali tried to demur but the wizened old ruler knew a lie when it was uttered no matter how lovely the lips that spoke it.

He sent his favourite concubine back to the harem and then called his chief wazir and instructed him to arrest Anarkali before the night was through. ‘You should bury the witch alive and leave no marking of her cursed tomb’.

In the years that followed Lahore was abuzz with rumours and theories of what happened to Anarkali. Salim was depressed as she was nowhere to be seen. Had she been banished back to Iran?

Eventually the old Mughal died and Salim ascended the jewel encrusted throne of Lahore. One of his first acts was to build a simple tomb on the spot where Anarkali had been so heartlessly murdered. Inscribed upon the tomb is a couplet from the love-lorn Jahangir himself, If I could behold my beloved only once, I would remain thankful to Allah till doomsday

[1] Pran Neville. Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 1997), 60.

Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

Rivers and Stories

His eyes might there command whatever stood

City of old or modern fame, the seat

Of mightiest empire, from the destined walls

Of Cambalu, seat of Cathian Can,

And Samarcand by Oxus, Temir’s throne,

To Paquin of Sinaen Kings, and thence

To Agra and Lahore of Great Mogul….

(Paradise Lost XI 385-91. John Milton)

Fourteen hundred kilometres due north of Bombay and seventeen hundred kilometres to the northwest of Calcutta, sprawled across the flat northwest plains, lay the fabled city of Lahore. The city, erstwhile capital of not just the Mughals but numerous Afghan, Arab, Turk and Hindu kingdoms, had a reputation that extended across oceans, continents and time itself. Lahore was mentioned in Egyptian texts and visited by travellers and adventurers from China and Arabia in the early centuries of the current era, all of whom valorised the river city as a place of incredible wealth, luxury and refined taste. Elizabethan poets and dramatists including Milton and Dryden, fascinated by the contemporary accounts of adventurers from France and Italy imagined Lahore to be one of the grandest cities ever constructed by humans. Even in the late 19th century, the Orientalist opera Le Roi de Lahore (The King of Lahore) by French composer Jules Massanet, ran to full houses and ecstatic reviews all across Europe and North America. It’s bungled-up quasi-historical plot, set in the 11th century, had Lahore ruled by a ‘Hindoo’ raja named Alim (a Muslim name!) who tries to rally his people to stop the Muslim invaders. Almost forgotten today, Le Roi de Lahore was able to succeed simply by playing on the city’s name, which more than any other conjured up the mysterious exotic Orient in the minds of 19th century Europeans.

Compared to Bombay or Calcutta, Lahore was a seeming backwater. It possessed none of the attributes of the sparkling imperial cities. Where Bombay was new and young, Lahore was ancient. Where Calcutta was the modern power centre of India, Lahore was the sometime capital of the recently vanquished House of Babur. The new colonial metropolises looked outward, beyond India, to the future. Lahore and its walled ‘inner city’ seemed to be the perfect symbol of an insular and irrelevant past.

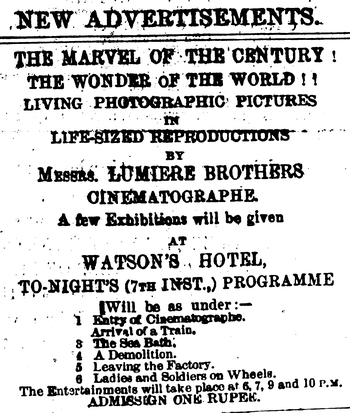

Far from the coasts, a distant outpost of Empire, there was nothing about Lahore that would suggest that movies, this most modern and technologically complex of entertainments, would take root here. In the early days (1900-1935) films were produced in all sorts of town across the subcontinent. Hyderabad, Kholapur, Coimbatore, Salem and even Gaya, reputedly the site of where Siddhartha Gautama meditated under a bodhi tree on his way to becoming, the Buddha. All had film production units, though almost all fell by the wayside after one or two outings.

Movie making was a cottage industry of sorts and anyone with a story and some basic equipment could shoot a short film. But as the audience for movies grew and with it a demand for meaningful and quality content (there were only so many wrestling matches and train arrivals you could stomach), production became concentrated in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. With the possible exception of the Prabhat Film Company, initially based in Kholapur but by 1933 centred in Poona (Pune), and which over a short life of less than 30 years produced only 45 films, Lahore was the only non-colonial city in South Asia to produce films of high quality, significant volume, in multiple languages over an extended period. And which continues to do so.

Why Lahore?

While Bombay, Madras and Calcutta had the location and access to new forms of capital and technology, the one thing they didn’t have much of prior to the arrival of the British was stories, the most ancient and beloved form of human entertainment. At heart, movies are nothing more than the most dramatic way of telling stories humans have yet invented. And prior to the arrival of Europeans, the three Imperial cities of India had little history. It was the British who conceived and built the cities; in essence their histories are inseparable from the history of the British Raj. This is not to suggest that the countryside around what became the three great Presidency cities was some terra nullius, devoid of human settlement and imagination. The islands of Bombay had been part of various kingdoms stretching back to prehistory and even under the Mauryas a regional centre of learning and religion. Various Hindu and Muslim dynasts had controlled the islands and, the settlements along the coast had well established links with far away Egypt. But by the time the English took possession of the islands they had lost any significant political or economic consequence. Prior to the East India Company there no Bombay.

So too with Calcutta and Madras. Though they were located in regions which had been part of ancient civilisations, both were mere villages that the English built into complex urban metropolises. Any stories that were told in these new cities had been brought in from outside. Bombay, Madras and Calcutta were blank canvases upon which was written a modern tale of interaction between Europeans and Indians. History was being created here. The past with its legends, myths and tales belonged to the countryside, the far away ‘interior’ from whence the cities residents had come to seek their fortunes.

Lahore, though, was different. It was not just ancient, it was still a vital, thriving city with a huge catalogue of stories stretching back to the very beginning of the Indian imagination. Like the other cities, Lahore attracted to it people from other parts of India but the stories they brought with them were absorbed into an already deep and luxurious sediment of fables, sagas and epics that remained every bit alive when the British arrived as they were when they were first told.

The Pakistani film industry, that which today some call Lollywood, is built more than anything upon this uniquely rich Punjabi culture. At the heart of which lies the immemorial city of Lahore. It’s worth taking a quick tour of this landscape to help us understand why the emergence of a movie industry here was not so much unlikely, as almost inevitable.

Treasure trove of tales

Punjab is the cradle of Indian civilisation. It was here in the land of five rivers (panj/5; ab/water) beyond which, in the words of Babur, Mughal India’s founding monarch, ‘everything is in the Hindustan way’, that the very story of India began.

Greater Punjab which includes all of the present day Province and State of Punjab in Pakistan and India, as well as parts of Khyber Pakhtunkwa, Rajasthan, Sindh, Haryana and Delhi, is home to one of the world’s richest, most variegated and dynamic of South Asia’s innumerable cultures. Peoples, and with them their stories, poems, music, gods, heroes, languages and ideas, have been flowing into the subcontinent via the Punjab since the earliest days of human settlement on the subcontinent. It is not in the least surprising that when the right historic moment arrived a lively and resilient cinema would be crafted from this treasure trove of material.

And to truly appreciate the deep roots of Pakistani films it is essential to have an understanding of the shared culture of language, song, theatre, poetry, storytelling and visual art that has distinguished this part of South Asia for millennia. It is from this profound tradition that Pakistani films initially took inspiration and upon which they continue to draw. And why, despite the many attempts to legislate against the industry, or even blow cinema halls up, Pakistanis keep making and watching movies.

Spies, scholars and antiquities

The good old man unfolds full many a tale,

That chills and turns his youthful audience pale,

Or full of glorious marvels, topics rich,

Exalts their fancies to intensest pitch.

Charles Masson

In 1832, while carrying out his undercover duties as a ‘news writer’ (spy) in the employ of the British East India Company, a certain Karamat Ali was taken by the recent arrival of a strange European in the bazaars of Kabul. Following from a distance he made mental notes of the character which he included in his next report to his control Mr. Claude Wade, British Political Agent in Ludhiana.

‘I would like to bring to your kind attention’ writes Karamat Ali in an undiscovered report, ‘the presence of an Englishman in the city. He keeps his hair (which is the colour of some of my countrymen who stain their beards with henna) cut close to his head. His eyes I have noted are the colour of a cat, by which I mean, grey and transparent. His beard is red as well. He appears to be a strong man as he has no horse or mule with him. His clothes are dusty from walking across the countryside and on top of his head he wears a cap made of green cloth. You may find it difficult to believe but he wears neither stockings nor shoes on his feet. I have learnt he carries with him some strange books, a compass and a device by which he reads the stars and thus makes his way from one place to the next. He answers to the name of Masson and speaks excellent Persian. I trust you will find this information helpful in your duties as Political Agent. Post Script. He could be mistaken for a faqir.’

Mr. Wade was well pleased with this information which he tucked away in the back of his mind. Over the next several years this mysterious Mr Masson continued to enter and exit official British communications like a phantom. Some reports had him pegged as an American physician from the backwoods of Kentucky. Others spoke of his brilliant command of Italian and that he was in fact a Frenchman. He popped up in Persia then Baluchistan; some reports detailed his convincing tales of journeys across Russia and the Caucasus.

But Afghanistan was where this strange morphing wanderer seemed most at home. He was reported to be interested in the history of some old earthen mounds outside of Kabul and had enlisted a number of the natives to assist him in his digging. Political Agent Wade kept tabs on Masson until finally three years after Karamat Ali’s report he wrote a letter to the wanderer with some shocking news. Over the years Wade had pieced together the mystery man’s history and in his letter he took great pleasure in letting Masson know about it.

‘I know who you are, Masson. And not just me. Calcutta is perfectly informed of your antecedents. The jig is up, old boy. You are not Charles Masson at all, sir. You are an Englishman and a traitor. Your true name is James Lewis born in London the son of a common brewer. You arrived in this ghastly country some dozen years ago as a private soldier in the Bengal European Artillery 1st Brigade, 3rd Troop.’

The letter which clearly made Masson panic went on to detail his history as a deserter from the Company ranks at Agra and the precarious position vis-a-vis his former employer he now occupied: he was due to be shot if apprehended. But Wade being a practical sort of man and a patriot had already received permission from his superiors to throw Masson a lifeline.

‘We’ve noted your excellent knowledge of several languages including Persian, French and Hindoostani. You also appear to be blessed with a natural ease in your interactions with the natives of the regions you have traversed. Your mind clearly, though not pointed in the proper direction, is sharp. In light of this and by way of making amends for your dereliction of duty and in recognition of the reality that the Tsar is intent on extending Russia’s influence into our Asiatic possessions, I offer you the following modest proposal.’

Wade informed Masson that if he would like to escape the firing-squad he would be wise to accept the Company’s offer to return to Kabul as its spy and to use his sharp mind, ears and eyes to keep Wade abreast of events in ‘lower Afghanistan and Kabul with special attention on the comings and goings of the tribesmen in support of Dost Mohammad but even more so the Russians.’