The shed was a vacuum. It seemed as if wind had never blown across this desert, which stretched to a horizon of tired hills near Afghanistan. Abdul Rahman hadn’t seen the fat man for five days. A guard with a moustache that covered nearly half his face filled the water container once a day and twice a day handed Abdul Rahman his rations. Things had improved in that way. Three chapatis, half an onion, potato curry most nights, but with the heat Abdul Rahman’s appetite had disappeared. He hadn’t slept for three nights but his mind was irritatingly active.

He wondered of the others in the lockup. Still there? At least I have this place to myself. He thought of the boy with glasses and of him being in Norway. Abdul Rahman could not recall ever having seen a picture of Norway, and the idea of the boy in a land full of white people, some place strange as another planet, made him smile.

He had a narrow view of the world beyond the bars of his window. Two buses pointed in opposite directions, like lumps of sugar covered with ants; people pushed big round bedding rolls, brass pots, and string beds through the windows. After storing their belongings men clambered on to the roof and waited for the journey to begin. Where were they going? A vague feeling of wanting to move on passed through Abdul Rahman. Where will I go?

His mind settled on a memory of her again. But it was a feeble hope. Why then do I stare into every woman’s face as if it were hers? He hadn’t stopped his search even now. Two years had passed, but his eyes still rose involuntarily to gaze with anxious trepidation into the faces of strangers.

Just a few weeks ago he’d been at the gardens around the big tomb in Isfahan. What a fool I was. It was just like her. Exactly her height, and the way she walked was perfect, even though the chador interfered with the movement. He saw her, alone. No Islamic beard and jacket around. She carried a bag, which he thought he recognised, and under her arm was a book. That was so typical of her. Never without something to read. She moved away into the sun which was setting against the minaret. He followed slightly behind on the path to the right of the rosebushes that ran in straight pink lines all around the geometric garden. I should not have hesitated but I was sure that man coming towards me wanted to ask me something. He was a Republican Guard in plainclothes. I was sure. But the man passed by without even a glance. She was too far ahead then. I should not have run after her. Indeed, he should not have. That was what caught the attention of the boy. Abdul Rahman had made an awkward jump over the rose hedge and was reaching out to grab the woman’s arm, when a boy with strong arms and thick weightlifter legs ran between them and gave Abdul Rahman a threatening shove. When she turned around I felt a fool. It wasn’t her and she quickened her steps. She thought I was after her purse.He turned away from the boy, who watched Abdul Rahman until he was sure that he had left the tomb’s garden.

*

The buses were gone. Abdul Rahman watched the moustachioed guard sitting on a bench against the wall of the petrol station. Bank notes flicked in his fingers. A good wad. The man put them into a tattered envelope and then reached beneath his uniform to deposit the envelope in an inner pocket. Three goats, a mother and two bleating kids, marched stiffly across the road and into the sand in search of scrubs. Heat waves made the middle distance seem watery and unstable. The hairy guard was nodding his head in conversation with someone else who was hidden from Abdul Rahman’s view.

The UN will decide who is a refugee and who is on holiday.

UN are not the police. They will ask you simple questions. To help you.

The UN will give you papers. And money. For you the UN is freedom to breathe free.

The UN was a concept as strange as Norway. Like that country, it existed on the edges of Abdul Rahman’s consciousness but only as a word. The UN had offices in Baghdad. The UN made statements against Iraq. Saddam distrusted the UN. And as he sat praying for a breeze to diminish the heat, so did Abdul Rahman. Why should I wait like the goat on Eid, for the knife to slit my throat? Maybe for the boy who wants to go to Norway the UN is not dangerous. For me it is poison. Who is UN to demand answers from me? I am not a criminal.

But he needed protection. He needed the card Fu’ad had mentioned. Why? I have travelled from Baghdad to this place without any such card. Only my wits have kept me alive.

That was true but then he had also had money. Not much but enough to keep the wheels turning and the buses moving forward. But now he was stuck. Even if he was out of the shed and a free man with his wits in top condition, without some money he’d be dead within days. I can’t deny it. I need some notes. But is UN the only source of money? There must be others.

*

Outside the shed door, the guard called out Abdul Rahman’s name as if he was a tiger who needed to be reassured that a human was approaching. Keys jangled against the lock. The mountains were just becoming visible in the early morning light. Breakfast time.

The door creaked open and the guard called out again into the darkness, ‘Abdul Rahman. Get up! Take your food.’

Bread, sliced tomato, and radish fell to the ground with a dull sound. The guard’s head twisted up, and in his confusion he lost his footing. Abdul Rahman’s hand covered the guard’s mouth. His unruly growth of facial hair tickled Abdul Rahman’s palm. The guard watched the Arab with wide frightened eyes. He was taking out a knife. Abdul Rahman removed his hand from the guard’s mouth and clutched the knife. With his other hand he groped inside the guard’s uniform until he felt the wad of notes, which he yanked out as if he were uprooting nasty weeds. The guard started to say something but he reconsidered when he felt the sharpness of the blade against his neck.

Abdul Rahman pulled up the guard’s shirt and cut a long piece of cloth. Then another. One piece of cloth went into the man’s mouth and the other tightly around his wrists. It wasn’t much of a fix, Abdul Rahman knew that. But maybe just enough to do the trick. Fifteen minutes is all I need. And some good fortune. Another cut of the dark blue shirt and the guard’s mouth was covered. Abdul Rahman removed the man’s belt and trussed his legs together.

Within three minutes the tiger was out and the cage locked.

Abdul Rahman ran across the road after an early morning bus that had been parked outside all night. With the bundle under one arm he couldn’t run as quickly as he had hoped, but he managed to jump up on to the back steps of the bus just as it was picking up speed. The conductor looked at him without any surprise and asked where he was going. But of course Abdul Rahman couldn’t say. He tried to remember the town where there was a saint’s tomb. ‘Peshawar,’ he said to the conductor who was shouting at the passengers and shoving them aside as he made his way towards the front of the bus.

The conductor stopped and turned towards Abdul Rahman. Then he laughed. ‘Peshawar?’ He laughed again. He disappeared into the forest of turbans and guns. Where are the women?Only men and odd shaped belongings that didn’t fit under the seats. The conductor’s voice could still be heard, but Abdul Rahman had lost sight of the man.

Two heavily bearded men who didn’t seem to be travelling companions sat on the back bench; Abdul Rahman squeezed into a tiny space between them. After twenty minutes the conductor was back with a grin. ‘Peshawar? No. No.’ His head was shaking back and forth. ‘Quetta.’

Abdul Rahman nodded in recognition and reached for the wad of money in his pocket. Ten dinars in Iraq is enough for most journeys. He peeled off two tenners and handed them to the conductor. The man held up five fingers. Does he want fifty or just five? Abdul Rahman hesitated and looked around for help but the conductor reached in and plucked out one more note. A fiver. He scrawled on a bright pink piece of paper and threw it at Abdul Rahman. ‘Peshawar!’ He still found it funny.

The terrain was rocky and dry. The bus barely crawled as it made its way through hilly passes. Nothing green. Only white heat and brown dirty earth. Camels and rock lizards frozen against the boulders were the only sign of life.

10.15 a.m. Abdul Rahman read the time on the thick, dirty-faced watch of one of the turbans who had fallen asleep next to him. The man snored energetically but the sound was buried under the desperate whine of the bus engine as it moved bitterly up a dry valley wall.

Suddenly, a checkpoint. Three vehicles and a tent and lots of men in blue uniforms with guns. Some sat on a string bed picking their teeth. Others jumped into the bus and began pushing their fingers into the passengers’ belongings. One of the blue uniforms tapped Abdul Rahman’s knee to make way. Abdul Rahman ignored the man and continued to look out into the desert. The man tapped again and gave the knee a slight push. Abdul Rahman stiffened his leg in resistance. The policeman grunted at Abdul Rahman and told him to stand up and when he didn’t, he pulled Abdul Rahman up by his jacket and dragged him from the bus.

Another blue shirt sauntered over and reached for the bundle under Abdul Rahman’s arm but he refused to relinquish the ledger. The bus had jumped into gear and was pulling away. Abdul Rahman stepped forward to get on but the blue shirts held him back and signalled for the bus to keep moving. The one who had pulled him off led him to a rickety table outside a faded white canvas tent and indicated that Abdul Rahman should sit on the ground. Abdul Rahman stayed standing. The bus was out of sight. He was alone with the police. Again.

Hours passed. With only his handkerchief on his head he squatted in the sun like a rock lizard. The police took turns checking all the vehicles going either way. When it wasn’t their turn to check they sat in the tent on the string bed paging through Abdul Rahman’s ledger as if it were a saucy magazine. Their friends came over and together they giggled at some of the pictures; they turned the pages quickly this way and that looking for something more interesting. But it soon bored them and after an hour one of the men wanted to sleep, and tossed the ledger into the dust below the bed. Abdul Rahman felt an urge to jump up and rescue the book, but they had already beaten him. Not much, but who knows what they would do next? Anyway, the sun had sucked every ounce of energy from him. If he couldn’t hold the ledger, at least he wouldn’t let his eyes stray from it and so he stayed where he could see it. Passengers on the other buses thought the man squatting there with a hanky on his head staring intensely into the tent was a complete madman.

More hours passed. The blue shirts had lost all interest in the ledger and in their strange Arab. Abdul Rahman had not spoken a word since being pulled off the bus and this irritated the police. They had discussed him among themselves and concluded he was a criminal but then, when he didn’t move, they decided that maybe he was just a mental case. His book proved it. All those newspapers clippings and writings. The collection of a deluded mind. As he sat in the sun, refusing to eat the oranges they offered him and hardly blinking, their attitude changed. They felt sympathy and one of the policemen tried to convince the others that he should take the Arab to the mental ward at Quetta Hospital himself. But while they were inclined to treat him more humanely they still believed someone with more authority should be told about this strange fish. Messages were passed by every means possible. Lorry drivers and conductors on vehicles going in both directions were given instructions to tell either the DC in Nushki or the Superintendent of Police in Quetta about the Arab, and to ask that someone send further instructions on how to proceed. Or better yet, send someone personally to handle the situation. Now it was just a matter of waiting. Who would respond first? Quetta or Nushki?

Around five in the evening a white jeep pulled up at the checkpoint. Abdul Rahman lay sleeping on the string bed. The blue shirts had taken him in as if he were a wounded and stray dog. His book was wrapped up and lay next to him. In his sleep Abdul Rahman had the feeling that his feet were made of iron and that he would never be able to get up to walk. He opened his eyes to see a man with a red beret shaking his foot. And behind the red beret, smiling like a fox, was the fat man in the baggy pyjamas.

*

The drive back to Nushki in the fat man’s jeep took no more than two hours. The sun was still bright when they pulled into the gates. But the sun had set and disappeared for many hours and was starting to rise again when Abdul Rahman was pushed back into the shed from which he’d escaped just twenty-four hours before. This time the leg irons were not removed. His hands were free, but for what reason he didn’t know because there was no water or jerry can to lift. The ledger had been taken from him the moment the fat man’s men had started to beat him. With thick bamboo poles. For an hour at a time. The man with the big moustache was especially vigorous, whirling the bamboo high over his head before landing it on the Arab’s back and stomach. The fat man disappeared. What did he care? If the UN asked what had become of the Arab asylum seeker, who would question that he had escaped and run back into Iran? This is the desert after all. You can’t patrol every square metre of it every minute of the day.

At the end of the first day, Abdul Rahman was given two cups of water and a soft black banana. One guard held the cup to Abdul Rahman’s swollen lips but left the rotting banana for him to figure out. All the while another guard held his rifle in Abdul Rahman’s face. The following morning he received the same ration, but no banana. The guards held their noses because the smell of urine was all over Abdul Rahman, but they still didn’t take him out to piss. He barely opened his mouth to take in the water, but the guards knew he was hungry. Why was his stomach growling so loudly then, if it didn’t crave food? When they locked him in for another night they twisted their moustaches and smirked.

If they had stayed in the shed with Abdul Rahman, the guards would have thought he was dead. His eyes lay partially open but showed no light. Flies buzzed around his head and sat on his lips, but he made no move to bat them away. In fact, the only sign of life was the irregular, ever-so-slight movements of the Arab’s Adam’s apple as he swallowed and gasped for moisture.

But the body is only the outward manifestation of life. Inside, Abdul Rahman’s mind had become alive with the beatings and deprivation. Years of maintaining his ledger, hours of reading and memorising the pages, absorbing each detail of his relatives’ lives as if he were studying the lives of the saints, had sharpened and fired his imagination. Lying on the oily floor his body seemed to belong to another. His mind watched the broken man on the floor for a time, without any pity, and then soared into another realm.

Major Abdul Rahman al Fazul is soaring higher and higher into the skies. The planets are moving aside for Major Abdul Rahman. The stars on the shoulders of his uniform are sparkling brighter than the hottest sun. Though he moves with great velocity, not a hair is misplaced from his head, which is crowned with a deep blue beret that matches the dark heavens.

The Prime Minister, Mr Haider al Haji Younus, is discussing the affairs of State with his staff in the grand office of the Prime Ministry.

‘Who was that smart Major at the reception yesterday?’ The Prime Minister addresses one of his numberless assistants. The Prime Minister’s finely etched purple lips form each word as if he were the archangel giving birth to sound at the beginning of time.

‘His name is Abdul Rahman al Fazul, your Excellency,’ comes the reply. ‘He is one of the brightest and most dedicated servants of the State. He is also the grand nephew of your mother’s cousin, Tofik al Misri.’ The satraps of Babylon bow their eyes before the Prime Minister and hum a low tone as they wait on His Excellency’s next word.

‘Wah! He is my relative! How wonderful!’ The Prime Minister stares out the window, his breast pumped full with affection. ‘Is this not fascinating.’

The satraps hum in unison, ‘Oh yes, your Excellency. Oh, yes. Most fascinating.’

‘I must meet my relative. Have Major Abdul Rahman report to me as soon as it can be arranged,’ the Prime Minister orders.

‘Of course, your Magnificence. We will bring him even sooner.’ The Prime Minister’s personal assistants set the mysterious and glorious wheels of State in motion in search of Abdul Rahman al Fazul.

Abdul Rahman’s celestial journey continues. Comets are nothing compared to him. Bursting stars turn dark and refuse to shine again in his presence. Miraculously he comes to a gentle but firm landing before the the Prime Minister, in a palace glittering with jewels and protected from harshness by soft silk carpets. The Prime Minister eyes his relative with wonder and appreciation looking him up and down again and again. Abdul Rahman revels in the gaze of Mr Haider Younus. He can feel the man’s respect and grace entering his own body. His limbs and crevices are being slowly but surely injected with a solution of admiration. Major Abdul Rahman is not moving, not blinking. Only waiting before the Prime Minister for hours. He is a sphinx. An Assyrian god carved in stone. The satraps are whispering and humming in astonishment at the Major’s amazing feat.

At last the Prime Minister addresses Abdul Rahman.

‘Major Abdul Rahman al Fazul. I am notified that you are the grand-nephew of my mother’s cousin, Tofik al Misri.’ The purple lips hardly move but the words carry like a trumpet’s flare. ‘You are my blood relative. This news pleases me. I have hundreds of relatives. It is not remarkable that such a one as I should have so many relations.’

Satraps and sycophants wag their heads and hum with closed eyes.

‘But what truly pleases me is that you have never approached me for a favour. One of the brutal hazards of high position is the unending river of letters I receive from all sorts of relatives requesting me, dare I say, demanding me, to make their life easier upon this earth. But you have never done so. Why?’ The Prime Minister awaits a reply from Major Abdul Rahman.

‘Your Excellency. It is not my place to make such requests.’ Tofik al Misri’s grand-nephew Abdul Rahman snaps.

‘[R]Wah! Wallahi![R] What heavenly words. What a wonder this is! A man who is truly good and great.’ Primer Minister Haider is clapping his hands together with glee and sighing. ‘But I must insist, it is my turn to demand, that you make one request.’ The Head of State is pleading with his relative Major Abdul Rahman.

After much reluctance and hesitation, which only increases the admiration the Prime Minister’s feels for his humble and valuable relative, Abdul Rahman requests. ‘I wish nothing for myself, your Excellency. It is my heart’s desire that my daughter Zubeida be appointed as a lecturer at the University. She is very clever and my joy is her success.’

The leader gazes at Abdul Rahman, as if in disbelief. ‘Of course, you may rest assured Major. It is done! Your daughter will be lecturer. And a success. But clearly her accomplishment will be only the outcome of her father’s unselfish devotion.’

As soon as these words are pronounced, like a promise from the mouth of the archangel, the Prime Minister departs the room. Behind him swish his satraps and attendants, moving him forward on their protective resonant hum.

IX

Baghdad, May-July 1987

Abdul Rahman had deliberately forgotten everything his father had ever tried to teach him. But one of the man’s favourite expressions, lodged deep in Abdul Rahman’s consciousness, had guided him to this day: ‘Heart pure, destination sure’. All his successes, his steady, sure rise from Ministry clerk to Senior Inspector in Jihaz Haneen, had been the result of Abdul Rahman’s pure intentions and honest motivation. Each new upward step was achieved not as an opportunity to flaunt his own glory, but for the sake of Zubeida. He wanted only that she be proud of him. Any material gains acquired as he rose gradually through the ranks had been used to support her studies. Greed had never fascinated Abdul Rahman; his wife’s lust for baubles and trinkets was a vice that embarrassed him but which he tolerated as a concession to domestic harmony. Habit, routine, and efficiency: these were the impulses that moved Abdul Rahman through life like the knowing currents of the ancient river Euphrates.

And efficiency flowed not just through Abdul Rahman’s small government flat on the seventh floor of a concrete tower in north Baghdad, but through his workplace as well. His office was at the Ministry’s al Jamouri Street complex. Four large, rectangular buildings facing in on a courtyard stood ominously behind a high whitewashed wall trimmed on the top with razor wire and glass. No sign indicated to which department these buildings belonged or what government business was carried out in them, but everyone knew. They hurried past if they were on foot, and never looked at the soldiers who stood at rigid silent attention twenty-four hours a day. It was a place of tears; a real hell filled up with devils. Inside, were dank, blackened halls, cracked concrete walls, interrogation rooms soiled with blood. Chips of bone and hair lay in the corners like dust in an uncleaned kitchen. Thousands of criminals, terrorists and enemies lived here and very few ever left.

Abdul Rahman’s office on the fourth floor of the western building was small, but it was a room of pure function, revealing nothing beyond what he called his respect for orderliness. Although she had never seen it, Abida sometimes brought things from the market for her husband to take to his office — plastic rose bouquets or framed views of waterfalls — but he regarded them with the same attitude he would a wounded bird brought in from the lane by a cat.

‘I prefer my working environment to be free of clutter, with only the minimum of instruments and no adornment,’ he said, each time she showed him her purchases. ‘Without order, Abida, even in simple matters such as arranging my working papers and writing tools, life becomes inefficient. Establish order and there is no risk of confusion. In my office everything has its place.’

And everything was in it.

On his desk, in the centre and six inches from the top edge, he’d placed a light green onyx penholder. A black pen stuck out of a black plastic cover. Next to it, a red pen protruded from a red cover. To the right of the penholder lay a worn pincushion in which several of the pins were rusty and bent from frequent use. Even though the pins made his fingers bleed sometimes Abdul Rahman preferred pins to staples; he’d been pinning things together all his life.

At precisely eleven p.m., not eleven fifteen or ten fifty-five, Abdul Rahman began his day. At two fifteen in the morning he drank coffee with his friend Aziz in the canteen on the third floor, and if possible always sat at the table closest to the pay box. If someone else occupied the table he found that his coffee tasted bitter. At two thirty-five he was back to work until six thirty-five when for an hour he made final notes with his black and red pens on the night’s work.

The first two hours of each evening Abdul Rahman spent alone in absolute quiet. Silence was essential to familiarise himself with the ‘patient’. Bakers, printers, drivers, housewives, students, doctors, mechanics, masons, hotel keepers, young pilots, imams, Christians, barbers, nurses, radio announcers, TV repairmen, cooks, middle-aged computer analysts, Muslims, motorcycle repairmen, atheists, writers (same as atheists), actors, old, retired engineers, women, men, boys, grandmothers.

All patients.

All of them diseased.

They had been detained by the Amn or Mukhabarat, the eternal accusing fingers of the Ba’ath State. Thousands of fish were trawled up in their secret nets each week but the tastes of Abdul Rahman and Jihaz Haneen were refined; they grabbed only the most succulent of the catch. The fattest tuna. Those overachievers who believed they were able to analyse the world better than the Party. Those who fancied dipping, not just their toes, but their entire leg into the pool of politics. Of course, few of Abdul Rahman’s countrymen were foolish or committed enough to risk everything they owned — families, careers, homes and possessions — for the trifle of personal political opinion, but clandestine groups and movements did exist, if you consider a group of five students to be a movement, or a band of Kurds a party. You could count these groups on your hands and still not touch most fingers, but they were just the sort of rare fish that made the stomachs of Jihaz Haneen rumble.

Haneen in Abdul Rahman’s language meant ‘yearning’. A consuming desire. The ache of desire. And al Jihaz Haneen was the Ba’ath Party’s Instrument of Yearning. It was distinguished from the other secret organs by the utter secrecy of the organisation itself, as well as by its ultra-sensitivity to the most subtle of threats to Iraq’s god-like President. Jihaz Haneen‘s hidden eyes were the thousands of hairs that stood to attention when danger was near and the chill that made the skin of the people crawl.

In each department, in every embassy and office in Iraq, even in each secret organisation, Haneen watched not the blockhead who thought himself clever enough to outwit the police, but the watchers; those closest to the heart of the Republic, Saddam Hussein, represented the deepest threat and captured Haneen‘s attention. Haneen was created to observe the most intimate circles surrounding the President and the Revolutionary Command Council. Senior bureaucrats and diplomats, members of the Party who had lost their conviction, even RCC members themselves. One unit monitored nothing save every movement of every member of the President’s family. Twice a day the unit filed reports on what each child, including his sons Qusay and Uday, were up to. And where. And with whom. Saddam read these reports, it was said, without fail and eagerly.

Al Jihaz Haneen was not simply one organisation among many which anyone could choose to join. Abdul Rahman and his colleagues had been selected, predestined he sometimes imagined, to be a part of the holiest of holy Ba’ath organs. And he knew that he was capable and worthy of his position only because he kept himself pure to the same degree that the others, his patients, dirtied themselves. Extravagance, vanity, and insensitivity to the ‘Higher Demand’ may suit the purposes of the ignorant, but for people such as Abdul Rahman they were to be avoided at all costs. Unfortunately, there were some, even some high up the Party ladder, who had yet to learn this most fundamental lesson. Among them was the most colourful butterfly in Abdul Rahman’s ledger: Haider al Haji Younus, Deputy Minister of Industry 1975–1979; Minister of Industry 1979–May 1987; Prime Minister of the Republic of Iraq May 18–July 4, 1987.

*

After waking each afternoon, Abdul Rahman’s normal routine, from which he never wavered, was to bathe, take a glass of coffee, then read the newspapers, even though he had no great inquisitiveness about political affairs. One afternoon in May, the President’s rough threats uttered the previous evening to a group of senior officials, sat across the front page of Babel like a roadblock. He eyed the paragraphs with boredom; at the top of the second column the Prime Minister, Mr Izzat Qureshi, was called ‘the mangy, simpering pet of anti-national interests’. Nothing unusual in that. Saddam had always found his Prime Minister overly ambitious. He had been given his position only because pressure from some European countries, which threatened the supply of weapons unless he was appointed, was too great for even the President to withstand. The Persian War had just begun and weapons were in short supply, so Saddam was forced to agree to external demands. But he had never stopped looking for a chance to dismiss Mr Qureshi.

The day after Abdul Rahman read Saddam’s insulting remark about the Prime Minister, Mr Izzat Qureshi announced his retirement. Due to heart problems. Incredible! Such a young, virile man as he. But even more incredible was a declaration by the President that the Minister of Industry, Mr Haider al Haji Younus, was to be the new Prime Minister. The Presidential declaration praised Haider Younus’s efforts as Industry Minister and expressed the President’s confidence that, unlike Mr Qureshi, the new appointee understood the historic role played by Prime Ministers within the government of Iraq.

The unexpected news of his relative Haider’s good fortune elated Abdul Rahman for days. ‘How can I express the joy that floods me as I read this news?’ He beamed at Abida, but she just turned up her nose. Like always. He folded the paper and returned upstairs to his bedroom. A sensation of heat tingled through his fingers exactly as if he was full of electric current. Inside his room he picked up his ledger and found the pages devoted to Haider Younus. Abdul Rahman had never met the new Prime Minister but he knew each and every one of his achievements, and he was confident that Haider Younus would far exceed the hopes of the President. Haider had never been ambitious and Abdul Rahman was confident that his relative would not commit the error of his predecessor and grab for more power. Haider Younus was self-disciplined; he had made an approving note to that effect in the margin of one of the ledger pages. Haider’s promotion confirmed to Abdul Rahman that, like a kite taking to the wind, his own affairs as well would soon receive a positive lift.

With his fingers shaking, Abdul Rahman traced his relation’s family tree and gazed at the photos he had collected. These were the lines of blood which connected them. The new Prime Minister’s mother-in-law was a distant cousin of Abdul Rahman’s mother. Both women traced their families through a wealthy landowner, Tofik al Misri, ‘The Egyptian’, famous in the area since the last century. Before achieving the post of Industry Minister, from which the President had plucked him to be Prime Minister, Abdul Rahman’s distant cousin had been a humble small-trader of steel pipes in Kirkuk. By 1968 and the final victory of the Ba’ath Revolution his interest in business was overtaken by a mad enthusiasm for politics. Haider was one of the earliest and strongest supporters of the Party after the revolution, and his goal became to attain a visible government post. In 1975, as a result of his unflagging political activity, Abdul Rahman’s relative was at last appointed as junior Deputy Minister of Industry.

Four years later, Haider Younus’s career entered its most impressive phase. His ascendancy from junior Deputy Minister, without access even to an official vehicle, to one of the most important ministries in a country flooded with oil money, coincided with the public exposure of the Muhyi-Ayash conspiracy. That same event, the plot against feeble President al Bakr, catapulted not only Haider Younus to the pinnacle of his dreams but enhanced the status of his unknown, admiring, lowly relative, Abdul Rahman al Fazul.

That day, after reading the surprising news of the promotion of his relative, Abdul Rahman closed the ledger, then shut each eye as if he were pulling down first one window shade then the other. He settled back and before long was flying through the firmament. As he flew, a voice like that of a narrator of a newsreel filled the bedroom.

*

In those days before Comrade Saddam Hussein became the Arab Nation’s proud head, President al Bakr made a State visit to Europe. During the President’s absence some few misguided members of the Revolutionary Command Council led by the Secretary, Muhyi Rashid, plotted together with the Syrians to pressure the President to resign. President al Bakr was an old and ill man. Muhyi and his friends were sure that the President would be unable to withstand their threats, and like gamblers they had convinced themselves of their good fortune before the roll of the dice. Muhyi planned to be appointed President. The Minister of Industry and the plotters’ main channel to Syria, Mohammad Ayash, was waiting to be declared Prime Minister.

However, through the vigilance of the strong Ba’athist organs the plotters’ conspiracy was decisively foiled. When the President returned to Iraq he called an urgent meeting of the Revolutionary Command Council. The conspirators, headed by Muhyi, were stunned when President al Bakr himself announced his own resignation. ‘I am ill and too weak to continue in this important role,’ he told his colleagues. Although his was a grievously difficult decision to take, the President knew that the appropriate moment had arrived when the man chosen by history to lead the Iraqi State forward should be charged with his noble responsibility. Right then and there he handed all powers and offices to the Vice President, Saddam Hussein. Muhyi’s men’s hatred of Senior Comrade Saddam Hussein was well known and they were aghast that the President had made his own move before they had managed to issue even one threat.

‘How can this be?’ the traitor Muhyi jumped up, nearly in tears, when al Bakr made his announcement. ‘This is inconceivable. If you are ill why not take a rest?’

Other plotters, gathered around the table, wore bloodless expressions; their hands twitched with nervousness. Of course, Comrade Saddam understood the plotters anxiety for what it was, and over the next week, under head of Ba’ath Party Intelligence, General Petros Zalil’s personal interrogation, Muhyi implicated twenty-two others, including Mohammad Ayash and a deputy Prime Minister. One by one they were arrested.

Assisting General Zalil in his momentous task was a loyal and humble servant of the State, Abdul Rahman al Fazul. Through years of patient observation and intricate, nay, delicate prodding, this great man had uncovered the treachery of Muhyi and his lackey Ayash. Such a tale deserves to be told and retold to the young men and women of Iraq and held forth as a revolutionary beacon of vigilance and patriotic endeavour.

Abdul Rahman al Fazul of al Khazamiyah village uncovered the evil intentions of the plotters when he noted that a junior official in the Ministry of Industry had been delegated to participate in an overseas ministerial mission in the place of Minister Mohammad Ayash. He further discovered that Minister Ayash was meeting secretly with Muhyi Rashid at the latter’s personal residence in Karbala. Due to information collected by Inspector Abdul Rahman, over many years in a special volume, the smoke of suspicion was transformed into the flames of conspiracy. As a loyal obedient servant of the powerful Iraqi Ba’ath Arab State, Abdul Rahman al Fazul forwarded the information he had gathered to the Director General of Jihaz Haneen, General Petros Zalil, who in turn passed it to the President, Comrade Saddam Hussein al Tikriti.

On the day Muhyi was presented with the evidence of his exposed and useless plot at a special meeting of the RCC, President Saddam invited Abdul Rahman al Fazul to accompany the head of Party Intelligence to the meeting.

Abdul Rahman is saluting Supreme Comrade President Saddam. He takes his seat next to General Petros Zalil against the wall behind the long wooden table around which the nervous members of the RCC sit. President Saddam speaks. ‘General Petros Zalil of Party Intelligence will now provide details of the investigation to this point.’ The President is smiling directly at Inspector Abdul Rahman.

As General Zalil speaks, the President continues his observation of Abdul Rahman al Fazul and covers him with benevolence and honour. He is reaching forward and grasping Abdul Rahman’s hand and bringing him close like a brother or son. His voice is strong and clear like mountain water. ‘Thank you Abdul Rahman. You have done a high service to your country and the State. Such men as you are what Iraq requires.’ Abdul Rahman dares not open his mouth in front of the greatest of Arab leaders. The gratitude of the Iraqi people, nay, the entire brotherhood of the Arab Nation, will forever be extended to Abdul Rahman al Fazul for his role in exposing the conspiracy.

After the meeting of the RCC, the new Iraqi Presiden,t Saddam himself, ordered prominent Party members from every region of the country to come to Baghdad with a rifle. On August 8, 1979, the traitors are executed by the hands of their fellow Ba’ath Party colleagues. Displaying such firmness President Saddam Hussein demonstrates his suitability to lead the Republic by firing the first shot and putting an end to the dirty life of the conspirator Muhyi Rashid.

Within days Abdul Rahman’s relative, Haider al Haji Younus, is appointed Minister of Industry to replace the plotter, Mohammad Ayash. And in December, Abdul Rahman is granted, for his role in exposing the conspiracy, the rank of Major.

*

‘Do you see, Abida, the practical benefit of this ledger?’ he asked his wife the day Haider received his promotion. ‘I am not mad. I have not followed this religion because my mind is idle. Rather, events of great significance arise mysteriously from my practice. A boost to my own destiny will be the result of the lift Haider’s career has received.’

But Abida did not see. She persisted in her refusal to believe in her husband’s religion.

That afternoon, after reading the President’s declaration promoting his distant cousin to be head of the Iraqi State, Abdul Rahman was touched again by the heat of approaching advantage. But how quickly good things can fade! Abdul Rahman could not have imagined the shock he was to receive when, just a few weeks after he had been elevated to his new height, Mr Haider Younus, the Prime Minister, praised by Saddam Hussein himself, was arrested!

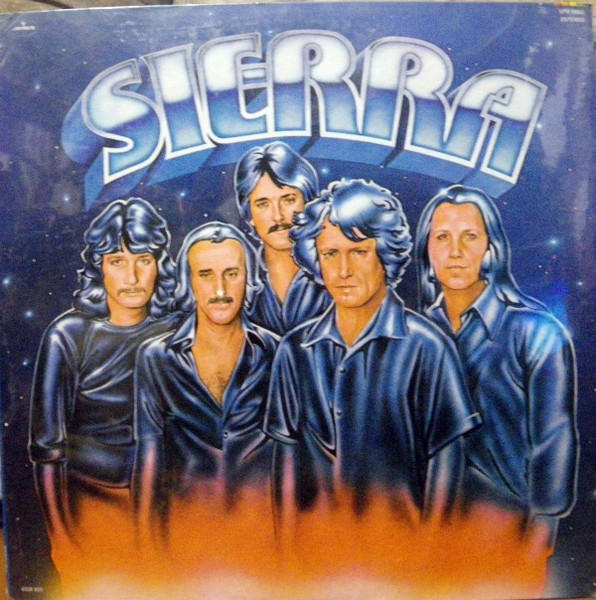

One of those albums that sunk like a stone. Released and then gone. Mores the pity, because this collection of 11 songs by Sierra is more than just alright.

Sierra was a single-album band of refugees from a bunch of country-rock and rock bands of the late 60s. By 1977, when their only and self-titled record was unleashed upon the buying public by Mercury, the individual players were in the sort of professional limbo that comes about regularly but is usually swept under the carpet in the biography. Which is too bad and a bit unfair, because Sierra was made up of some formidable names with very respectable curricula vitae.

Gib Guilbeau, on rhythm guitar, had played in a whole series of country-rock and proto-Americana bands like The Flying Burrito Brothers, Swampwater and the legendary Nashville West. On drums, Mickey McGee had credits as the drummer for Jackson Browne (Take it Easy), JD Souther, Linda Ronstadt, Chris Darrow, and Lee Clayton (Ladies Love Outlaws), not to mention an early country-rock outfit Goosecreek Symphony. Oh, and late Flying Burrito Brothers! Eddie’s nephew Bobby Cochran contributes blistering lead guitar and lead vocals. ‘Sneaky’ Pete Kleinow’s steel has graced hundreds of rock and country rock albums and was first brought to wide attention as a founding member of The Burrito Bros and New Riders of the Purple Sage. On bass, Thad Maxwell, another vet of the 68-75 scene, and band fellow of Gib in Swampwater. Felix Pappalardo Jr. produced and contributed piano parts. A storied figure, throughout out his life Pappalardi supported or produced everyone from Tom Paxton to Cream, not to mention his own weighty Mountain.

So, no slouches these guys. They were not suburban lads looking for a break. Their combined talent and credits were formidable. In the parlance of job advertisements they had a “proven track record” of making excellent music.

But alas, here the sum of the parts didn’t add up. Which is not to say this a shit album. Far from it. Sierra is a very good record of late 70s American pop and deserves to be hauled up from the bottom of the deep lake of forgotten country-rockers.

The art work is a put-off and no doubt played a big part in the record’s stillbirth. A perfect example of a cover designed by some free lance artist with no idea about the sort of band Sierra was. Many styles did they play, but spacey country-disco was not one of them. You could be forgiven however for thinking this was in fact, their speciality, if you had access only to the dumb, lifeless cover art.

On the black wax we are treated to high quality examples of soft rock (Gina; If I Could Only Get to You), So Cal country-rock (Farmer’s Daughter; She’s the Tall One), British blues (I Found Love), top 40 slick pop (Honey Dew), boogie, rock ‘n’ roll (Strange Here in the Night; I’d Rather be With You) all sauted in the spicey warmth of the Tower of Power horns. (In this era if you were good enough to entice the ToP to record with you, you were ensured at least one extra star from the reviewer.)

But it didn’t work. The album suffered not from a dearth of talent or poor production. It sank because it had no focus. Spaghetti was all over the wall, perfectly al -dente no doubt, but spread across too wide a plane. For country-rockers in search of Gilded Palace of Sin or even One of These Nights, this was bland stuff. Waaay too poppy, man!

But for this old guy living 50 years in the future, and slightly anxious about the coming extinction of human made music, Sierra deserves 7 stars out of ten, for capturing several trends of America popular music current in 1977. Especially the eternal wrestle between Country and Rawk.

There are some blatant and pointless rip-offs like You Give Me Lovin, which is essentially a copy of the Eagles, Already Gone, but what did more than the front cover to kill this album, is its refusal to rise above the very good level. The album should really have been titled, Bob Cochran and Sierra, as he is the real star. It is Bob (the only non ex-Burrito), who shows the most excitement here. His guitar is sharp and always stands out. His high-tenor voice fits perfectly in both soft rock and pop—audiences the record label was clearly trying to attract. Sadly, the band of sages behind him seem content to play perfectly, expertly, confidently but, alas, with very little real energy or pizzaz.

Ratings:

Musicianship-8/10

Listenability-8/10

Energy: 6/10

Songwriting: 5/10

Cover: 3/10

Historic Value*: 7.5/10

*a subjective ranking of combined significance & interest to the history of North American (mainly) popular music of the 1970s. Judged by myself on a particular day. Significance could include the musicians, the cover art, the producer, production quality, songwriting, influence, innovation, listen ability etc.