Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

Of the many Parsi clans who leveraged their interaction with the British in Bombay to establish themselves as economic powerhouses, even to this day, the shipbuilding Wadia family is worth a closer look.

Even before the community fled Persia to seek refuge along India’s western coast, the Zoroastrians were renowned ship builders and sailors. During the reign of King Darius (522-486 BCE) the Persians had learned well from the Phoenicians (1200-800 BCE) and become the acknowledged shipbuilding and maritime empire of the epoch. Though their numbers were tiny in their new home in India, (never more than 100,000) the community kept these ancient skills alive.

Settled and working out of Surat, the Wadia (Gujarati for ‘ship builder’) clan, interacted with the various European trading nations—Portugal, Netherlands, France—that sought trade with the Mughal empire and its wealthy business communities of Gujarat. When the rather slow-starting English received the islands of Bombay from the Portuguese, Parsis began to migrate from the hinterland south. One of Surat’s most prominent shipbuilders, a Parsi named Lovji Nusserwanji Wadia who had built ships for a number of European trading firms in Surat, was invited by the English to establish a branch of the family business in Bombay. And so, beginning in 1736, Lovji along with his brother Sorabji set to work building Asia’s first dry docking facility where EIC ships could be drawn entirely out of the water to be repaired and refurbished. This single bit of infrastructure increased the economic and strategic value of Bombay immensely. It brought to the foreground Bombay’s exceptional qualities as one of the best deep water harbours (the city’s name derives from the Portuguese words Bom (good) and Bahia (harbour)) from which the British, with their new infrastructure and world-class Parsi shipbuilders, were able to not only vanquish the Portuguese, Dutch and regional Indian naval powers but also clear the Arabian Sea of pirates which led to a steady increase in traffic and trade. By the mid-19th century Bombay had become a major international commercial and naval port and the most important city in British India.

By 1759 the dry dock was operational. At the same time the brothers Wadia were providing many of the ships that carried cotton and spices and eventually that fateful black gold, opium, from India to China and other Asian ports. Given the EIC’s monopoly on the Indian trade and the massive growth in the economy opium facilitated, particularly in the first part of the 19th century, the Wadia’s became immensely wealthy. Theirs was a full-service enterprise, building single-sailed sloops, water boats that managed trade up and down the west coast, beautifully sleek, fast-moving clippers, well armed frigates and man-o-wars for the military as well as cutters, schooners, and eventually steamships for the Asian/Chinese trade. Using teak, rather than English oak for the hulls, the Wadia’s ships were lighter and more resilient than ships made in Britain. Over the years, the family built over 400 ships for the EIC’s Maritime Service and others including their fellow Parsi sethias.

Lovji’s grandson, Nusserwanji Maneckji continued the family business and in addition to servicing the British became a much sought after local agent for early American traders building up the trade between India and New England. Maneckji Wadia was so well regarded by the Americans that he and his relatives enjoyed a virtual monopoly on the Yankee business with many American traders exchanging effusive letters with him in which his ’impeccable character’ is praised and his family compared to ‘satraps’. Both sides profited handsomely. In the words of one Yankee businessman, they profited ‘monstrously’, recovering up to 300% on the Indian textiles and other goods sourced by the Wadias.

One of Nusserwanji’s sons, Jamshetji Bombanji, was appointed Bombay’s Master Builder[1], a role usually held by an Englishman, but which the Wadia family was to hold for 150 years running. Several of Bomanji’s ships found their way into the larger events of the time, including the first man-o-war built in India—a huge warship with three masts and loaded with 74 large cannons—the HMS Minden. When it set sail in 1810 a Bombay newspaper, the Chronicle, praised “the skill of its architects” and went on to note that with “the superiority of its timber, and for the excellence of its docks, Bombay may now claim a distinguished place among naval arsenals”. Several years later, on the night of 13 September 1814, the HMS Minden was tied to a British ship in Chesapeake Bay, along the east coast of the United States, after a local lawyer, Francis Scott Key, had helped to secure the release of an American prisoner-of-war held by the British. Fighting between the Americans and British was intense with the night sky flashing red and yellow. The frightening spectacle inspired Key to write a poem, The Star Spangled Banner, which was eventually adopted as America’s national anthem.

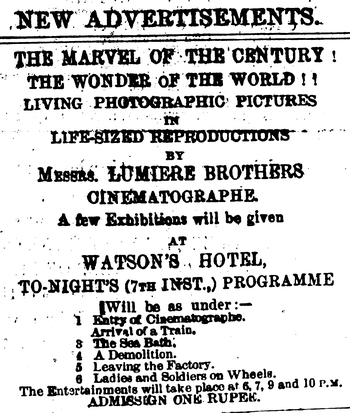

Steel eventually replaced teak in the building of ships and steam took over from wind. The Wadias, like many Parsis diversified initially into textile production where steam-derived technologies helped to propel the Wadia’s Bombay Dyeing mill into one of the most successful and iconic of India’s modern businesses. And when the movies came to India, two great-great grandsons of Lovji Nusserwanji took the daring decision to turn their back on textiles and ships altogether and embrace the world of moving pictures.

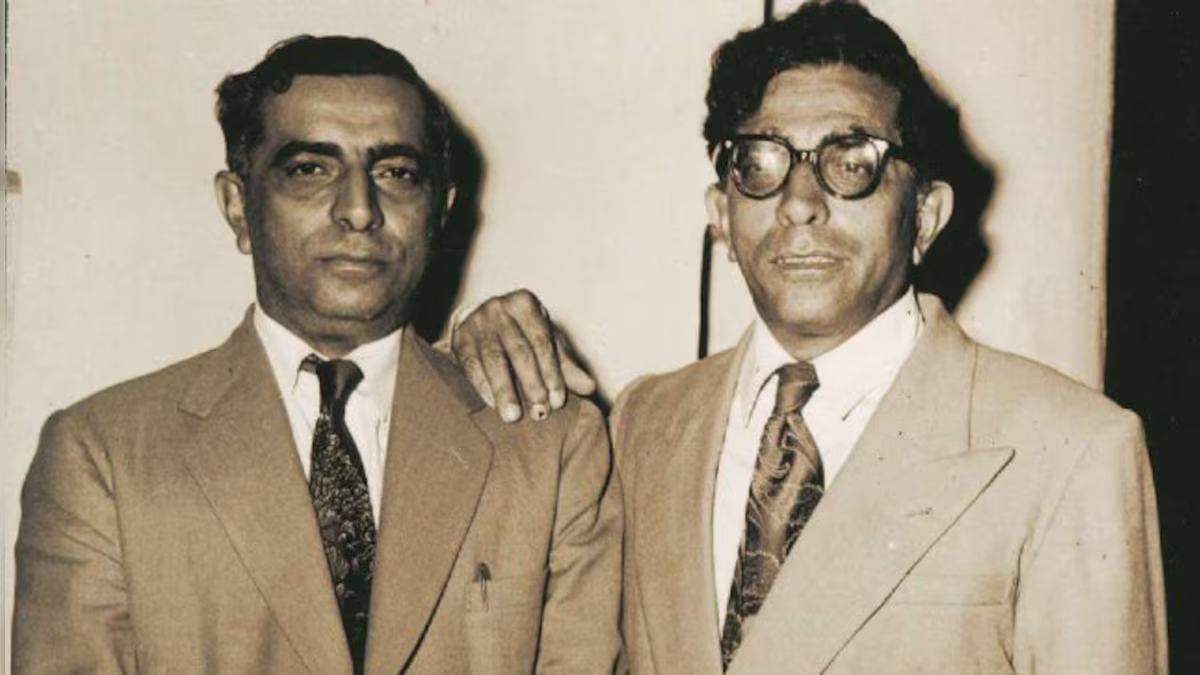

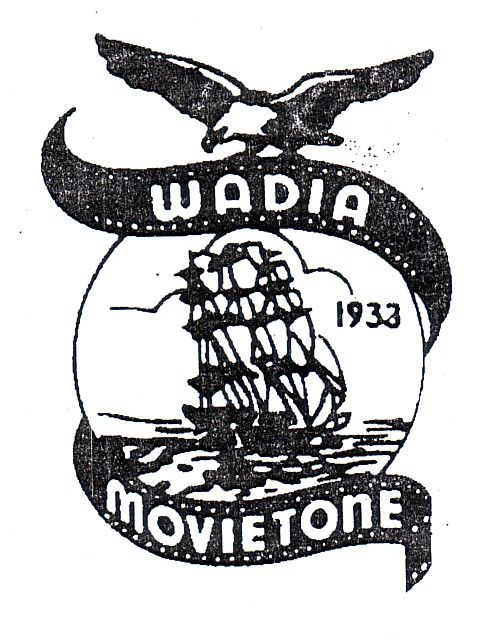

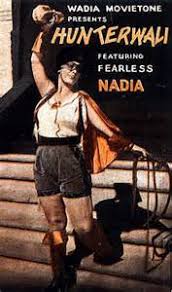

Jamshed Boman Homi Wadia, known as JBH, was only 12 when Dadasaheb Phalke exhibited Raja Harishchandra, but spent his youth captivated by the Hollywood films that were becoming an increasingly common form of entertainment in Bombay. Though well-educated as a lawyer JBH horrified his family with his announcement that he intended to make films for a living. He quickly found work with the then prominent Kohinoor Studios producing a dozen films for the studio, some of which saw moderate success. But being an entrepreneur JBH didn’t want to work for anyone else, so, joined by his younger brother Homi, launched his own studio, Wadia Movietone in 1933, retaining the family’s shipbuilding past as part of the studio’s logo.

The brothers became icons of the early Indian film history and throughout the 30s and 40s Wadia Movietone was the most profitable of all Indian filmmaking enterprises.

Wadia Movietone studios was financially backed by several other Bombay Parsi families-including the famous Tatas-and grew into one of the most successful and consistently profitable studios of the 1930s. The brothers were basically in love with stunts and action. They especially adored derring-do characters like Zorro and Robin Hood played by Douglas Fairbanks Jr, and blatantly copied many of Fairbanks’ movies for Wadia Movietone. When Fairbanks visited Bombay, JBH made sure the actor visited his own studio; so impressed was his American idol that Fairbanks agreed to sell the Indian rights of his mega hit Mark of Zorro to Wadia Movietone.

The brothers proudly low-brow fare of fistfights, speeding trains and masked heroines dominated India’s box offices throughout the 30s and became the most popular genre in India at the time. Sadly, as film historian Rosie Thomas states, Indian “film history was rewritten”, by starchy Hindu nationalists who objected that stunt films did not inspire sufficient pride in India’s Hindu classical past. The whole stunt movie genre was effectively eliminated from most histories of Indian film giving virtually all attention on the more staid and far less fun, middle-class targeted ‘social’ melodramas focusing on family and relationships.

At their height, however, the Wadia brothers’ studio was the rage of the box office. Their greatest success was without a doubt a series of action films which in today’s parlance might be called a franchise, starring a stunning white woman they billed as Fearless Nadia.

Mary Evans, a West Australian girl of Scottish-Greek extraction, moved in 1911, at the age of three, to India where her father served with the British army. Settled and schooled for several of her early years in Bombay, Evans father was killed in 1915 while fighting in France and eventually moved to Peshawar to live with an ‘uncle’ who in fact was a friend of her deceased father. It was the wilds of the NW frontier of India that stimulated Mary’s tomboy personality to blossom. She discovered a love for the outdoors, sports and horse riding and with a mother who had once been a belly dancer, found herself singing (often bawdy songs) and dancing on stages across the NW and Punjab. Between 1927 and 1934, Mary performed as a dancer and singer in various troupes and circuses as well as a solo performer, travelling across the Indian subcontinent performing for wealthy maharajas as well as illiterate labourers. It was a risky job for a slightly big boned, well-built blonde-haired woman, travelling (often) alone across India, speaking only English and Greek, working at night in (often) seedy venues but it was one that seemed to suit her. When an Armenian fortune teller predicted a bright career for Mary, they used tarot cards to select a stage name, eventually settling on Nadia.

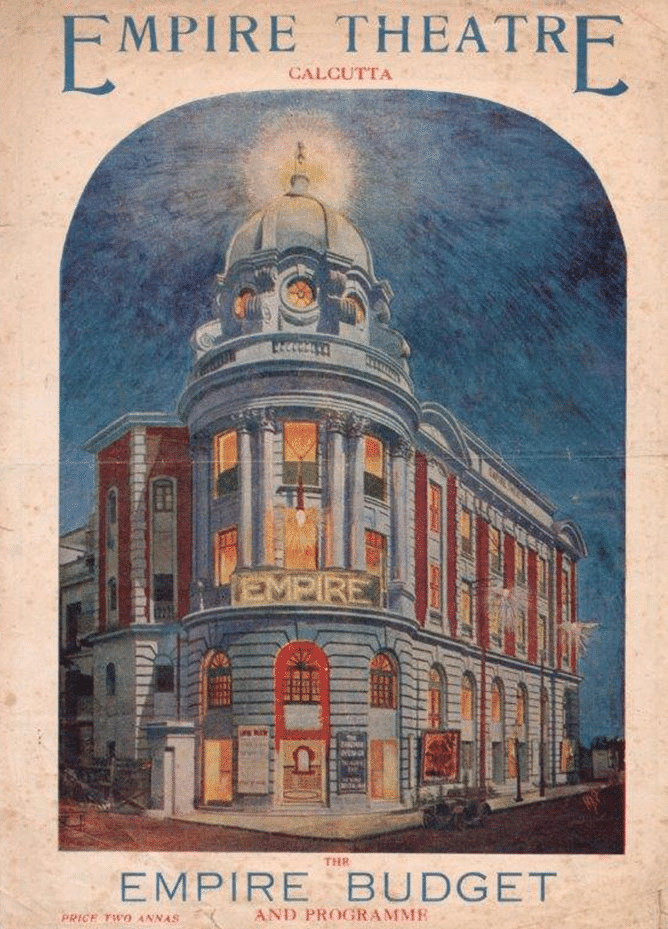

Sometime in the early 1930s, a Mr. Langa, the owner of Lahore’s Regent Cinema, saw one of Mary’s stage shows. Given that cinemas in those days regularly booked dance troupes to complement the movie, it is possible Langa hosted Mary at the Regent itself. Whatever the circumstances, Langa was taken by her presence and striking looks. He offered to introduce Evans to a friend of his, someone named JBH Wadia, who ran a movie studio in Bombay. Was she interested? With sparkling blue eyes and blonde hair, Nadia hardly fit the bill as the ideal Indian woman but she was not alone. Throughout the silent era and even into the age of Talkies, many of India’s initial generation of female starlets were in fact Anglo-Indian (mixed European and Indian heritage), European and Jewish women. At a time when acting was considered a dishonourable career by most Indians, non-Indian women felt less inhibited socially to take to the stage. Most adopted Indian stage names and worked hard to improve their unmistakably foreign accents. Still, the basic assumption was that actress was a synonym for prostitute. German film historian, Dorothee Wenner, whose biography of Evans, Fearless Nadia, sums up the situation as follows:

The connections between theatre, dance, music and prostitution remained so closely entwined well into the twentieth century that any official attempt to limit prostitution simultaneously represented a threat to the dramatic arts. The consequences for cinema were first felt by the father of Indian cinema, D.G. Phalke. He knew that filming made different demands on the realism of scenes than the stage did and therefore he wanted a woman to play the female lead in his first film Raja Harischandra. It was 1912 when he went looking around the red-light district of Bombay for a suitable performer. Although the impoverished director offered the few interested parties more money than they would normally earn, all the prostitutes turned the film work down…it was below their dignity!”[2]

When they met, Wadia immediately understood Evans’ appeal and potential. He suggested that the Australian change her name to Nanda Devi and wear a plaited dark wig. But Mary refused. “Look here Mr Wadia,” she said, undeterred of her future employer’s power or status, “I’m a white woman and I’ll look foolish with long black hair.” As for the name change, she scoffed. “That’s not in my contract and I’m no Devi! (goddess)” She pointed out that her chosen stage name, Nadia, resonated with both Indian and European audiences, and also just happened to rhyme with his own name, Wadia. JBH, not used to be spoken to so boldly by an employee, let alone a woman, figured she just might have what it takes to make it in the movies. He hired her on the spot.

An agreement was reached and in 1935 the brothers tested her in a couple of small roles in two films. Her charisma, not to mention her stunning and exotic looks, were obvious. She stood out like a ghost at midnight. Immediately, she was offered the lead in a Zorro-like picture called Hunterwali (Lady Hunter) which became a smash hit and is now considered one of the most significant milestones in South Asian film. The Wadia brothers had been unable to find a distributor for their extravagant production. Most considered it too radical and unsuitable for local tastes. A white masked woman, cracking a whip, smashing up villainous men, riding a horse and sporting hot pants that revealed her very white fleshy thighs? Absolutely not!

Unbowed, the brothers pooled their resources and sponsored the film’s premier at the Super Cinema on Grant Road, on a wet June evening in 1935. This was make or break. The Wadias believed in Nadia even though everyone else did not. Not without a little trepidation rippling through the cinema the lights dimmed and the show began. Fifteen minutes in, as Nadia pronounced that ‘From now on, I will be known as Hunterwali!’, the working class male audience stood up, cheered and clapped and in their own way pronounced the coronation of the Queen of the Box Office, a title she would hold for more than a decade.

The Wadia’s, as indeed most of their countrymen and women, were politically active (supporting Independence from Britain) and socially progressive. They championed women’s rights, Hindu-Muslim solidarity and anti-casteism. Though official censorship prohibited open discussion of these themes the Wadias made sure their superstar made casual references to them. As Nadia herself said, “In all the pictures there was a propaganda message, something to fight for.”[3]

The girl from Perth via Peshawar and Lahore, was now a superstar of action and stunt film with millions of fans. Known and billed as Fearless Nadia she insisted on doing all her own stunts be it fistfights on the top of a fast-moving train, throwing men from roofs or being cuddled by lions. She starred in nearly 40 pictures most made by the Wadia brothers (she married Homi in 1961) with such fantastical titles as Lady Robinhood, Miss Punjab Mail, Tigress, Jungle Princess and Stunt Queen.

In 1988 a version of Hunterwali, perhaps the most famous of all of Nadia’s films was released in Pakistan, starring Punjabi movie icons, Sultan Rahi and Anjuman.

[1] A highly critical and strategic role that oversaw ship design and construction but innovation, compliance with international shipping regulations and development of the shipbuilding industry.

[2] Wenner, Dorothee. 2005. Fearless Nadia: The True Story of Bollywood’s Original Stunt Queen. Penguin. Pg. 79.

[3] Thomas, Rosie, “Not Quite (Pearl) White: Fearless Nadia, Queen of the Stunts”, in Bollyword: Popular Indian Cinema through a Transnational Lens, ed. Raminder Kaur & Ajay J Sinha (New Delhi: Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd, 2005) 35-69.