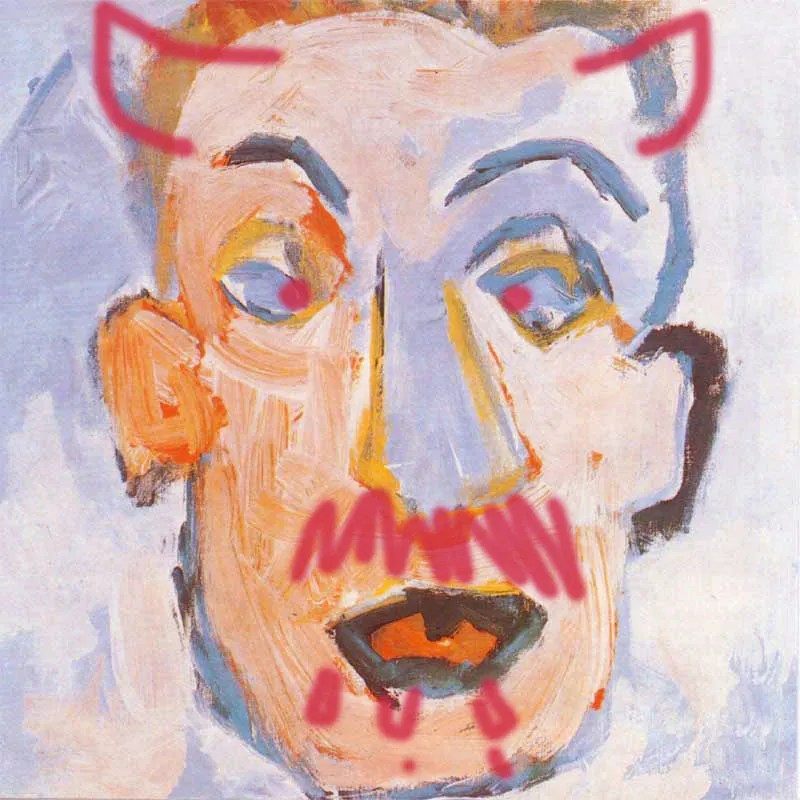

Bob Dylan: King of Country Music

Taking the voice of both subject and object, in 1964, Bob Dylan put out one of his defining public statements in the song, All I Really Want to Do.

He assures his lover that he has no interest in classifying, categorising, advertising, finalising, defining or confining her. The same lyrics can be read as well, as a plea to his fans for a reciprocal respect.

And yet, here I go.

Alongside the many ‘Hello! My name is…’ stickers we’ve slapped on his lapel—voice of a generation, Nobel Laureate, fundamentalist whack job, protest singer—I would like to suggest the following: Bob Dylan, King of Country Music.

I’ve sensed this forever, but as I listened to a mixtape I posted recently, it has become clear as day.

Dylan was not just inspired by Hank Williams, Cash and Woody Guthrie, he has throughout his career, drawn deeper on the well water of country music than any other so-called genre. It wouldn’t be too hard to argue that very few albums in his vast catalogue are NOT country or country-rock albums. Bringing it All Home; Highway 61 Revisited; Street Legal jump to mind immediately. Of course there are some others too, but generally the sonic atmosphere of country music and his approach to his art is heavy and sticky with Mississippi mud.

I will go further.

Dylan is a better country singer than a rock ‘n’ roll singer. His voice tends to divide the public. A lot of people can’t stand it. Croaky, wheezy, shallow, awful, they saw. I am obviously not in that camp though it’s hard to deny that of late it is pretty tuneless and frail. I prefer the adjective, quirky. Country music loves quirky; Bob’s nasally and rough delivery fits perfectly alongside that of others like Kris Kristofferson, Jimmie Dale Gilmore or even Willie Nelson. So too his quirky pronunciation and phrasing. Very country.

It works another way too. Some of his quirkiest songs, like Dogs Run Free, a wired and weird folk-jazz oddity on New Morning (1970), is transformed into a perfect country ballad on Another Self Portrait (1969–1971): The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10. Nothing weird or wired. A curly song like this works much better as straight-ahead country. As I’ve mentioned before Dylan’s Bootleg Series are chocker block with alt.country versions of almost every song he’s ever sung. And often these studio scraps are better than his more famous rock and folk stuff. Honestly.

My I admit as evidence, One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later) a sparkling, sneering gem from Blonde on Blonde (1966 and recorded in Nashville with country session players). An all time personal favorite. But he also released an instrumental version on The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12: 1965–1966, The Cutting Edge. The song works in both idioms and as a western canter, outshines, for its short duration of 4 minutes 57 seconds, any Chet Atkins instrumental.

At the height of his artistic powers he could release two outstanding albums in the same year, 1975. Blood on the Tracks, his mid-period masterpiece and The Basement Tapes, a double LP of random musical experiments and frolics that qualifies as the first perfectly formed album of ‘Americana’ music. Both albums are perennial near-the-top finalists in every ‘Best Albums of Dylan’ list ever published.

What followed in TBT’s wake (recorded 1967-68 but released in 1975) were John Wesley Harding (1967) a proto-Outlaw country album, and Nashville Skyline (1969) pure country pop in which Dylan channels Jim Reeves.

Even during his ‘lost 80’s’ period, some of his most memorable songs were his country ones: You Wanna Ramble & Brownsville Girl (Knocked Down Loaded/1986); Silvio & Shenandoah (Down in the Groove/1988); The Ballad of Judas Priest (Dylan & The Dead/1989). The last is really a Grateful Dead track. Dylan’s singing is pushed along by the band’s amazing rhythm section and Jerry Garcia’s delicious guitar, but it demonstrates that other masters recognised the country potential of his words and tunes.

Let me wrap this up by asking you to listen to this version of I Shall Be Released, recorded live with Joan Baez on the Rolling Thunder tour. Dylan’s voice is absolutely beautiful here. And Joan’s subtle but essential supporting vocals makes a fucking good song, a fucking masterpiece. It is such a spiritual, earthy rendition, with no artifice whatsoever.

Bob never is so relaxed as when he sings his country stuff. His unique timbre and phrasing don’t grate or stand out as weird. Sure, he was only 34 when he recorded this, but his voice is not just physically strong, his performance is one of complete commitment. Whereas his mid 60s stuff sometimes comes off as angry and performative, in this and most of his other country-flavored repertoire, he is nothing but authentic and true.