Chapter One: An Invention With No Future

Fifty one years to the day before India won its Independence, on 15th August 1896, the well heeled citizens of Bombay enjoyed a final evening of the most ‘marvellous’ spectacle the city had ever experienced. For several weeks, first at Watson’s Hotel in Kalaghoda and then at the Novelty Theatre on Grant Road, a Frenchman en route to Australia, had been delighting audiences with the latest hi-tech entertainment. Called the ‘cinematographe’ his contraption, which looked like an ordinary wooden box with a hand crank on one side and a small brass-encased lens on the other, was the closest thing to magic audiences could imagine. As the Frenchman rotated the crank a spool of thin grey film through which light flowed from a second box attached to the top, the most unbelievable photographic images danced against a white screen. In the darkened hall the rapt viewers wondered if they had not been transported to a new dimension.

The projection of moving pictures was the most exciting development yet in the short life of the revolutionary new science of photography. Two French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumiere had been experimenting with colour photography for a number of years and as a sort of intellectual side-project had attacked the problem of combining animation with projection of light. Just nine months earlier, in December 1895, at Paris’ Grand Cafe, the brothers had stunned audiences with the first commercial showing of a film, which over a span of 49 seconds, depicted a train pulling into a station and passengers jumping on and off.

The Lumiere brothers’ version of the movie camera-cum-projector was small and light enough to be carried about outdoors. At first, the inventor brothers didn’t know what to make of their apparatus. In fact, they saw it not so much as an idea whose time had come but, as Louis Lumiere said, as ‘an invention without a future.’ His brother put it even more emphatically: ‘our invention…has no commercial future whatsoever.’

But in direct contradiction of their conviction, the siblings launched a campaign to take the Cinematographe experience to audiences around the world. To assist them they contracted a fellow Frenchman, a pharmacist by trade, named Marius Sestier to be this new technology’s evangelist in the furthest end of the world, Australia. So dubious of their invention’s prospects were the brothers that a year or two later they put together a travelling road show complete with 40 magicians to tour Asia, the Far East and the Fiji Islands. If the moving pictures didn’t draw the crowds perhaps the wonder workers would be a profitable Plan B.

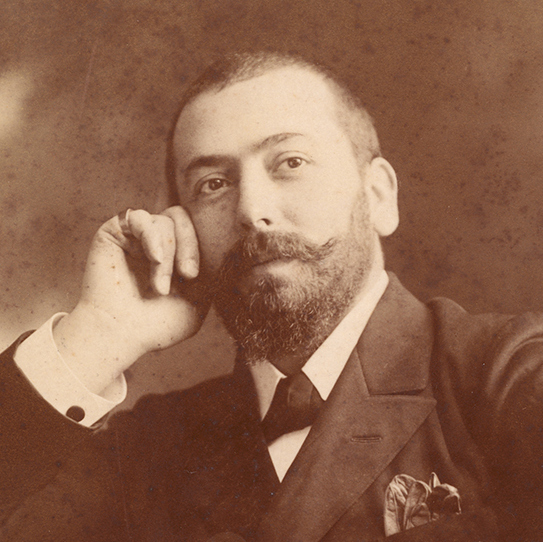

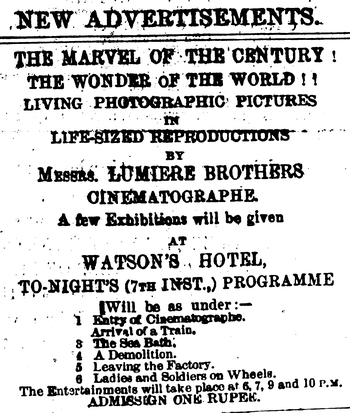

Sestier, who sported a trim beard and moustache with ends that curled confidently upwards in the style of an upperclass gentleman, set sail, with this wife, from Marseilles on 11 June 1896 with a passage to India. They docked in Bombay nineteen days later and though it seems Sestier knew little English, he immediately set out making arrangements for the showing of several films. Over a period of four nights people crammed into a small room in Watsons Hotel to watch six short films[1], including the much bally-hooed Arrival of a Train, all produced by the Lumiere brothers. The local papers proclaimed this new thing, ‘The Wonder of the World!’

The impact was tremendous and immediate. More showings were added (though one was cancelled due to an early case of load shedding) and additional, larger venues were secured. The local press gushed enthusiastically about this amazing Marvel of the Century but found Mr Watson’s hotel to be somewhat unsuitable. The Bombay Gazette’s reporter complained that because of “the smallness of the room, the operator is unable to have the instrument sufficiently removed from the canvas to make the figures life-size, and this has the further disadvantage that it makes the actors in each of the scenes move about rather too quickly.”

Sestier responded to the criticism by securing the premises of the Novelty Theatre as a corrective measure. Built in 1878, the Novelty was one of Bombay’s glittering new theatres along Grant Road, the city’s answer to Broadway. It boasted a large 90 x 65 ft. stage and accommodated 1400 people. The Lumieres were in business! At Rs. 1 a seat, Sestier grossed close to Rs. 100,000 (close to one million in contemporary terms) over more than 60 sold-out shows, which proved beyond any argument, that inventors should not be relied upon for their business acumen.

By the time Sestier boarded the French steamship Caledonien for Colombo and Sydney on 26th August, he had changed India forever. The movie bug had found a new host. Many Indians had attended the shows at the Novelty Theatre and one in particular, a photographer, Harishchandra Sakharam Bhatwadekar (aka ‘Save Dada’) was so enraptured he immediately placed an order for a Lumiere Cinematographe with the London firm Riley Brothers. The investment set him back a pretty penny but within three years Bhatwadekar had made and shown India’s first documentary film, The Wrestlers, which depicted a match at Bombay’s Hanging Gardens between a couple of popular local wrestlers, Pundalik Dada and Krishna Navi. Over the next several years Save Dada made a number of other films, all of mundane everyday subjects and reached his cinematic zenith by documenting the grand Delhi Durbar, a celebration of King Edward VII’s accession to the Imperial throne in 1903.

Save Dada was not alone. In Calcutta and Madras, other men (yes, they were all men) were just as excited about this stunning new invention. With a buzz that can only compare to the one we experienced when we received our first email or spent our first hours surfing the web, dreamers and entrepreneurs in every corner of British India sensed the magic of films and moved quickly to grab hold of it.

In Bengal, a rakishly thin lawyer, Hiralal Sen, scion of one of Bengal’s prominent Bhadralok families moved to Calcutta from Dhaka in 1887 to indulge his fascination with photography and cameras. Some years after his arrival in Calcutta, the legendary studio of Bourne and Shepherd sponsored a photographic competition which Sen, eager, like all budding photographers for some recognition, entered. When he won a prize, the young lawyer was so encouraged he abandoned the Bar and rather rashly established his own photo business.

Though photography had been around for nearly half a century by this time, it was still so new. Its possibilities intrigued practitioners who experimented with all manner of materials and processes. Everything had to be tested and tried. In between taking portraits of Calcutta’s citizenry Sen began experimenting with light by projecting shadowy images against the wall using a lantern and black cloth. But as far as we know, by 1896 Sen had not yet seen a motion picture.

This happy event happened in 1898, two years after Sestier’s shows on the other side of the country. A certain Mr Stevenson, one of those minor characters that wanders across the stage of history but about whom next to nothing is known, hired a swank venue on Beadon Street, the Star Theatre, where he exhibited a ‘Bioscope’ film that ran on the same bill as a popular stage play, The Flower of Persia.

Charles Urban, an American book and office supplies salesman with a fetish for silk hats, fell in love with movies from the first moment he put his eye to the peephole of a Kinetoscope, the early American film projector invented by Thomas Edison. Ever the salesman, Urban immediately cottoned to the commercial potential of moving pictures (even if Edison, like the Lumieres, did not) and arranged to be Edison’s agent for the state of Michigan. By 1896, as Sestier was wowing Bombay’s citizens at the Novelty Theatre, Urban was trying to sell Edison’s updated projector, the Vitascope from his shop in Detroit. A year later, after asking an engineer friend to come up with a better projector that didn’t ‘flicker’ as each frame passed through the light, Urban was marketing his very own Bioscope, a single wooden box more tall and narrow than Lumiere’s but like theirs with a hand crank. His projector had the added advantage of not requiring electricity to operate. The Bioscope was so successful that an English firm, Warwick Trading Company, invited Urban to move to London and head up the company with his Bioscope as its flagship product.

Given his family’s wealth it appears not to have been a big deal for Sen to fork out Rs. 5000 for one of Urban’s spiffy new inventions. Upon its arrival in India though the equipment was slightly damaged. And to complicate matters it came with no instruction manual. But Sen was not easily deterred. He sought out a European friend, a Jesuit priest named Father Lafouis, who assisted Sen in repairing the Bioscope as well as figuring out how the contraption functioned. Within a short time Sen had so mastered the Bioscope that with the financial help of his brother Motilal and two other investors, he established the Royal Bioscope Company in 1899. Sen quickly became an importer of European films and within a year had shot his own footage. Taking a cue from the mysterious Mr Stevenson, who appears to have moved on to greener pastures, Sen cut a deal with the Classic Theatre, to exhibit his films between acts of a stage play, as a sort of bonus entertainment. The first Sen film to gather notices was Dancing Scenes from the Flower of Persia, which was a popular stage production at the time. Encouraged by the public’s response Sen filmed scenes from other stage productions including Ali Baba, Sitaram and Life of Buddha which were then shown at other city theatres including the Star and Minerva. As in Bombay, the shows stunned the local press. “This is a thousand times better than the live circuses performed by real persons. Moreover, it is not very costly … Everybody should view this strange phenomenon,” gushed one local daily.

And it wasn’t just the residents of India’s most populous city that got to partake of this strange phenomenon. Royal Bioscope took their films to the countryside, setting up impromptu open-air cinemas in small towns across Bengal and Orissa, starting a practice of travelling movies that continues up to the present. Hiralal turned out to be an artiste of amazing inquisitiveness and is credited with making India’s first political film (fiery nationalist speeches denouncing the British Raj by Surendranath Bannerjee, a founder of the Indian National Congress) as well the first commercials for a certain Edwards Tonic and Jabaskum Hair Oil. He continued to film stage shows as well as produce short films of everyday life for a decade and a half but sadly his entire ouvre went up in smoke. Literally. In 1917 the Royal Bioscope Company warehouse caught fire and destroyed all his work and some of South Asia’s earliest and most important films.

Sen’s success ignited the imaginations of others and movies began their journey from novelty toward industry. Back in Bombay, in 1911, Dhundiraj Govind ‘Dadasaheb’ Phalke, another photographer cum magician cum printmaker was completely smitten after catching a film called Amazing Animals, a sort of early David Attenborough nature film, at the America India Picture Palace. He returned for more, this time buying a ticket to an Easter time showing of a French film called The Life of Jesus. ‘Why,’ he whispered quietly to his to his sceptical wife as they sat in the dark, ‘couldn’t I tell the story of our Hindu gods and deities on film, as well?’

How his wife answered we don’t know. But Phalke who had struggled up this point to find anything that could capture his interest for more than a few years at a time, and who’s several business partnerships had ended acrimoniously, spent the better part of a year buying up equipment and learning as much as he could about film making before travelling to England in February 1912 to meet with moviemakers and technicians. During this time one of Phalke’s correspondents was an American magician named Carl Hertz. Hertz had spent time in India tracking down fakirs who could reveal to him the secret of the Indian Rope Trick and meeting with the painter Raja Ravi Varma. Given subsequent events, in which he tours the South Pacific as part of the Lumiere brothers troupe of 40 magicians/ projectionists it seems likely that he may have met Sestier himself at one his Bombay movie exhibitions.

In any case, both men, Phalke and Hertz, were in Bombay around the same time and shared a passion for moving pictures and magic. In the years proceeding his cinematic career, Phalke for a time had billed himself as a magic man named Professor Kelpha, an anagram of his family name. In another intriguing twist Phalke had done business with Raja Ravi Varma through one of his other commercial ventures the Phalke Engraving and Printing Works. So it is possible that Hertz had met Phalke as well. After leaving India, Hertz integrated moving images into his magic show as a regular feature and went on to achieve a minor notoriety as the first man to show a film on a ship and in South Africa.

Phalke’s London sojourn was a lightening trip. He was back on Indian soil three months later, and on 1 April 1912, the very day he landed in Bombay, he registered the Phalke Films Company, and began putting together this first film, Raja Harischandra, based upon a legendary ruler of ancient India described in the epic Mahabharata and other literary works.

Released in 1913, Raja Harishchandra holds the official title as India’s first feature film. But in fact, a year earlier, in 1912, another enterprising Maharashtrian exhibited a movie titled, Shree Pundalik, at the Coronation Cinematograph at Girgaum. Most film historians reject the idea that it was in fact, ‘Dadasaheb’ Tornay, the maker of Shree Pundalik, who deserves the accolade as India’s earliest feature film maker, on the rather lame grounds that the camera was operated by a European named Johnson. And that the film was sent to London for processing. Had these criteria been sufficient to disqualify a film from being judged Indian, many films including some of the most loved such as the classic Pakeezah (1972) which was shot by German Josef Wirsching would also need to be removed from the canon.

But whereas Tornay failed–Shree Pundalik was a commercial flop–Phalke went on to make more than a hundred silent films many of which included his wizardry with special effects like the Hindu god Hanuman flying through the sky. After a falling out with his business partners Phalke, who rightly, is credited as the father of Indo-Pakistani cinema, retired to the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi, a somewhat disillusioned and lonely man. For years he resisted making more films but eventually agreed to accept an offer from the maharaja of Kholapur to produce one final film, a talkie called Gangavatran. Like many others Phalke struggled to cope with the transition from silent to sound films and was unable to repeat his early silent film success. He passed away in 1944 a forlorn and rather forgotten figure.

In the southern city of Madras, a dealer of imported American cars, Nataraja Mudaliar, was a fan of Phalke’s films, and like Sen, Bhatwadekar and Phalke just had to try his hand at the new craze. Mudaliar requested an Englishman by the name of Stewart Smith who was in town filming a documentary on Lord Curzon ( Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905), to give him several lessons on the finer points of using a camera. With a confidence that only the amateur can muster, Mudaliar, established India’s first film studio, the India Film Company in Puruswalkam. The year was 1917. Within a year, he had produced a series a well-received historical pictures including South India’s first feature film Keechaka Vatham, an episode from the Mahabharata, exhibited at the Elphinstone Theatre. The film was a smash hit by any standards thrilling audiences and netting Mudaliar Rs. 50,000. Excited by the money making potential of his film, Mudaliar arranged for it to be shown in cities outside of India with large Tamil populations including Rangoon, Singapore and Colombo. These venues further netted him a handsome Rs. 15,000. So infectious was this new art form that even the Father of Independent India, Mahatma Gandhi’s family was caught up. His son Devdas Gandhi, then a journalist, was hired by Mudaliar to write the script cards for Keechaka Vatham in Hindi, in order that the film could be shown in the north.

[1] During his stay in Bombay, Sestier screened between 35-40 films, all presumably shot by his sibling sponsors in France. They included such delights as Rejoicing in the Marketplace, Foggy Day in London and Babies Quarrels.