The political weather had been getting rough for a while. It seemed as if everybody had a knife sharpened for the bijou General with the face of a hawk. Gorby warned the Americans they were going to do a hit job on him. India always hated the guy. Najibullah, the barrel-chested leader of communist Afghanistan had thousands of agents in Pakistan looking for the opportunity. Even the Yanks were sick of his repeated moving off script. Oh, and don’t forget all the generals he had jumped ahead of when he was appointed Chief of Army Staff by the PM, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who he then turned around and deposed and had hung in his first spurt of manly Islamic machismo. The entire political class, civil society and media resented him. He had spent the last three months hunkered down inside his heavily protected residence, some say humming the blues lament, ‘Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jiving too.’

Dark clouds indeed.

But the 17th day of August 1988 showed not a cloud in the sky. Today, the “ill man with ill intentions”—the summation of his military commanding officer several years previous—was flying down to the deserts of southern Punjab to witness a field test of General Dynamics’ Abrams M1 tank. His American sponsors had been twisting his arm to buy a bunch of them. The American Ambassador, Arnold Raphel, and his military attaché would meet the President in the desert. Zia, as per his usual practice, would be accompanied by several of his top generals including his presumptive successor, Gen. Akhtar Abdur Rahman.

The Abram tank proved to be a dud. The Americans were embarrassed that it missed its targets and repeatedly sputtered to a halt, unable to handle the clay-laden dust of the Thar desert. Zia and his men were openly relieved. What they really wanted were AWACS. Still, the party was surprisingly cordial given the deflating exhibit of American tech and general ill-will swirling around the figure of the President.

After a nice lunch, the President invited the Ambassador and his attaché to join him in Pak-1, Zia’s Hercules C-130 transport plane with its specially fitted airconditioned VIP capsule for the hour-long flight back to Rawalpindi. No hard feelings, Mr. Ambassador. Now about those AWACS.

As everyone settled into their seats a couple crates of local mangoes of the best variety were stuffed on board. At 3:40 pm the giant aircraft lifted off. Eleven minutes later it nose-dived into the desert killing everyone on board bringing Zia’s unpopular eleven-year reign to an emphatic conclusion.

Strange things began to happen pretty quick smart. An order was given (probably by both countries) to do no autopsies. Why not? The FBI, who had just a year or two earlier been mandated by Congress to investigate every terrorist attack in which an American was killed was denied entry to Pakistan for a year. And when they did arrive, they seemed less interested in the crash then in sightseeing. Ohkaay. The Pakistanis settled on sabotage. The Americans on mechanical failure. After the tank debacle you’d think they were probably right but then again, no evidence has ever been produced along those lines. So, the Pakistanis were probably right. Right.

But what kind of sabotage and by whom? The latter was too hard to answer. Everyone wanted this prick out of the picture. How, was somewhat easier to answer. Eyewitnesses on the ground claimed they saw no smoke, no explosions, no missles hitting the plane. Remember it was a clear hot summer day. Just the damn plane genuflecting up and down and then smash.

Elaborate proposals involving military men and fast acting, time and altitude activated nerve gas were put forward. Ultimately, too much was at stake for the truth to be ever told and within a few months the drama and official curiosity was over. Pakistan had a woman PM, Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of the man Zia had murdered. To her the crash had been “an act of God”. The Soviets had been routed and the Yanks were heading home. Good riddance all round.

But what about those mangoes? No one denied they were put on board in the desert. Some claim every single piece (around 60) were checked by security. Highly unbelievable. Others claim they were shoved on at the last minute with no scrutiny. Much more credible.

Early reports appeared that traces of chemicals were found on the skin of some of the mangoes recovered from the wreckage. Had the nerve gas been hidden inside the fruit? The public loved this idea. And it remains the most popular explanation until today. A novel, The Case of the Exploding Mangoes got quite a bit of press in the late aughts.

Hmmm. No one can say for sure what actually led to the death of a dictator, his general staff and an American Ambassador. Leastwise, no one’s talking. But isn’t it interesting that those crates of luscious juicy mangoes were a late inclusion on the plane?

On another August day, twenty years before, another case of Pakistani mangoes, from the same region as those hitching a ride on Zia’s plane, did a star turn that has to be remembered as one of weirdest sidebars in modern political history.

Pakistan and China have been best friends forever. But their friendship was especially strong in the 1960s when Pakistan was still young and China was caught up in the whirlwind of an endless series of self-induced crises with Cinemascope names. The Great Leap Forward. The Great Famine. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. China didn’t have a lot of friends; the Pakistanis needed a big power to balance the friendship of India with the USSR.

In August 1968, the Pakistani Foreign Minister on an official visit to Beijing, gifted Mao Ze Dong (The Great Helmsman) a case of Sindhri mangoes, considered by many as the King of all mango varieties. Mao didn’t like the look of them. In fact, the fruit was pretty much unknown in China at the time, so the following day, as a token of his personal gratitude he re-gifted the funny fruit to a group of ‘workers’ who earlier in the week had subdued some angry students at Qinghua University.

Things were messy in China. In fact, the place was a real shitshow. Two years previous with the slogan, ‘Sweep Away All Monsters and Demons!’ the People’s Daily announced The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. With the stated aim of ridding society of all remaining bourgeoisie elements, the CR seemed to be more about Mao remaining the unchallenged leader of China, a position he feared was on somewhat shaky ground.

What ensued was a period of chaos in which students, with direct and active support from the Communist Party, formed themselves into bands of Red Guards denouncing, killing, destroying buildings and otherwise wreaking havoc against officials and political foes of Mao. The main cities across China turned into battlegrounds. Factions of Red Guards each claiming to be the true executors of the Chairman’s will, battled other factions of Red Guards. Public executions and torture sessions, wanton destruction of public property and street battles became the order of the day. Mao and the Cultural Revolution Group of senior Mao loyalists watched quietly; some in horror, others with glee.

But by the time the Pakistani Foreign Minister stopped by for a visit, even Mao realised he had unleashed a red wave of terror that even he could no longer control. A fresh slogan, ‘The Working Class Must Exercise Leadership In Everything’ was promoted and Mao invited workers to oppose the wild students.

After their victory at Qinghua University, Mao sent the Pakistani mangoes to various work sites as a gift. In a way that only those who live in such mad situations can make out, this was seen as a signal that power was shifting and the Red Terror of the students was over. Things were bound to better from here on in. And this strange fruit from friendly Pakistan was to symbolise that (unwarranted, as it turned out) faith.

Not sure whether they should eat it, one factory sunk their mango into a jar of formaldehyde to preserve it for posterity. In other factories people crowded around to sniff the fruit and stroke its smooth skin. Some boiled the rotting pulp—I mean mangoes are great but they don’t last more than a day or two or three—in water which they claimed became holy. If you took a sip, you were in direct touch with the Great Helmsman. A cottage industry popped up to produce wax replica mangoes encased in glass which were given pride of place in factories and workplaces. These wax mangoes became relics. Like the hair of the Prophet for Muslims or a Piece of the Cross for Catholics. Mao was amused but didn’t intervene. In fact, the Mango became a stand-in for the Great Man himself.

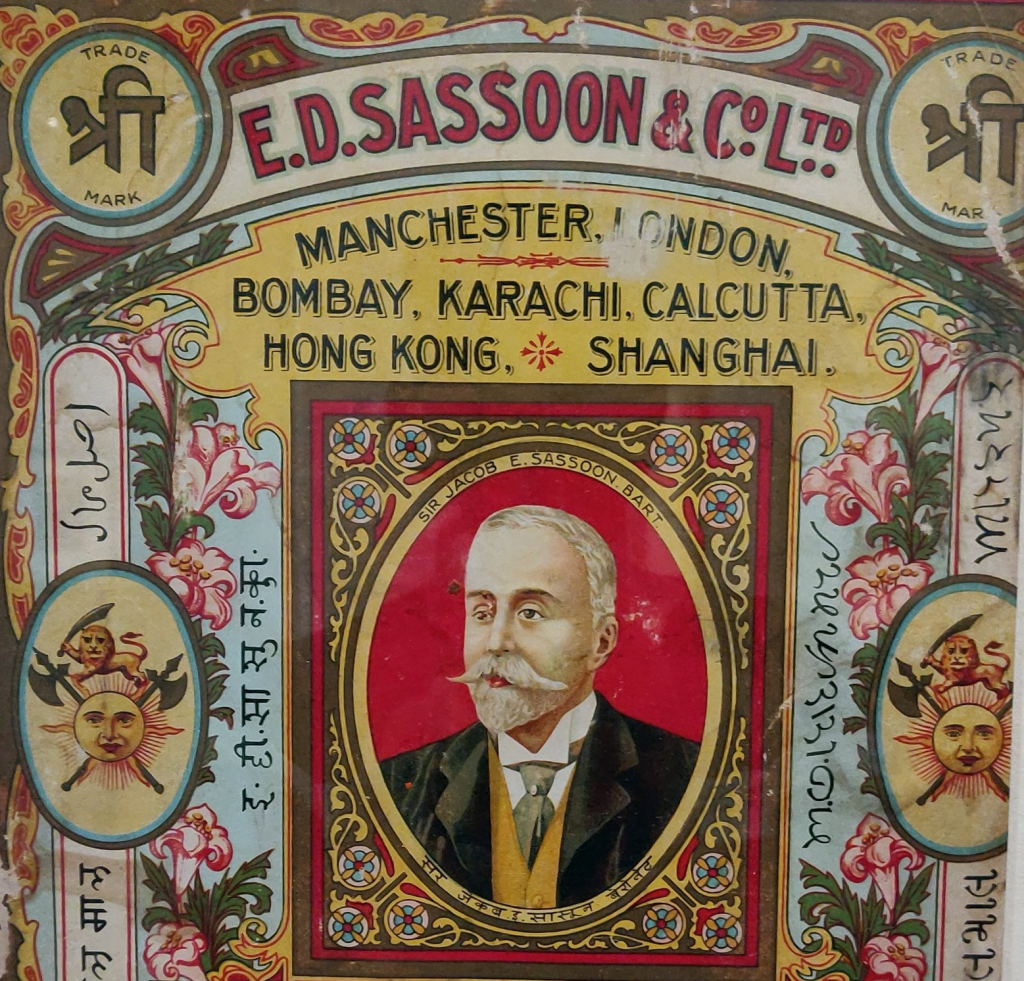

Mangoes were carried ceremoniously in parades on national holidays, flanked by portraits of the Chairman. The mangoes were toured around the country. In one case a plane was chartered to deliver a single mango to Shanghai. At a time when Mao had felt his personal following to be waning, the mango re-invigorated the Chairman’s personality cult. Mango posters, tea cups and plates appeared in the shops. There were reports of workers bowing in front the wax mangoes each morning as if it were an ancestor shrine from pre-Communist days.

From ‘68-’71, now feeling a bit more in control, Mao shifted his focus to the countryside. Millions of students and other bad characters were sent into the fields of China to learn from the peasants. Millions died. Others were not permitted to return to the cities ever again. Life across China was yet again completely disrupted. The economy severely damaged yet again.

The mangoes inevitably were forgotten as people struggled to survive, working the land with few tools, no wages and in inhuman conditions. All that remains, like the mango skins in the wreckage of Pak-1, is the story.