Lollywood: stories of the Pakistani film industry

From Punch houses to Parsi Theatre

Though the early years of the East India Company are remembered in history as a time when hundreds of British men came to India and rapidly became very wealthy, life in a small up-country district was tough. Though the British public, to the extent they had time to care, resented the new ‘nabobs’ who returned home to England full of ill-gotten wealth and social swagger, relatively few servants of the company actually made fortunes. Many stayed on in India after their tours setting themselves up as indigo planters or scrounging for work in the big cities. For those not part of the elite ‘Covenanted Officer’ class which included most non-Indians, the Englishman’s daily round involved three essential things: work, avoiding illness and drink, with the last usually combined with the first two. Alcohol consumption was both a way to stay alive–especially since local water supplies were contaminated—and a way to pass the time. The highest rungs of British society had access to a variety of European wines, porters and spirits. The sailors, soldiers and planters, on the other hand, could mostly only afford locally brewed (and occasionally, deadly) concoctions that mixed ingredients like coconut spirits, chillis and opium.

Though the origin of its name is contended (does it refer to the 500 litre wooden barrel that held it, known as a ‘puncheon’ or to the Hindustani word, panch, for the number 5, the number of ingredients) punch was an alcoholic innovation invented in India by early European residents who wanted a lighter, sweeter drink than the local spirits or fiery rum. Experimentation found that by mixing rum or arrack, sugar, lemon/citrus juice, rosewater and spices in water a very tasty and potent beverage emerged. As early as the 1630s, Englishmen were writing home about this new drink they called ‘punch’. When the Company’s ships returned from India loaded with exotic luxuries, the ships’ crew and locals enjoyed evenings together drinking Punch on the docks. Though the many of the individual ingredients (lemons, nutmeg) were expensive in Britain, punch became ‘the tipple of choice for English aristocrats’ for the next hundred years and since then has become a regular offering at parties, weddings and even church potlucks across the English-speaking world.

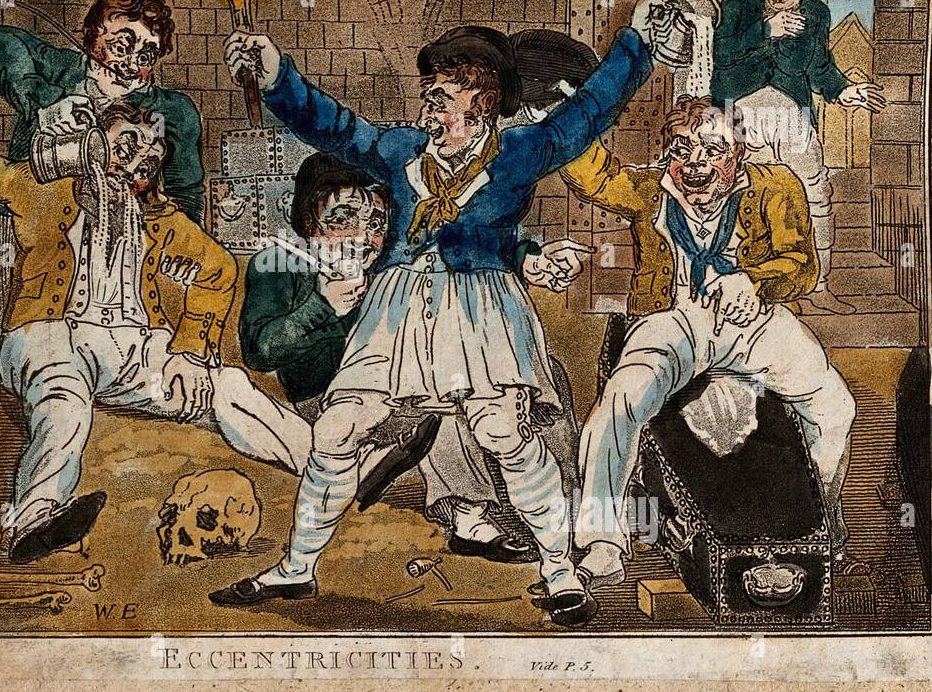

In India, however, the grimy taverns where such alcoholic drinks were sold became known as punch houses. Not dissimilar to the famous jook joints in the southern United States, famous for their cheap booze and violence, punch houses were perfect venues for drinking binges, rowdy roughhousing, fisticuffs and whoring by bored sailors, down on their luck Europeans and soldiers. Indeed, one Englishman summarised the entertainment available for the British lower classes in India as amounting to “drinking hells, gambling hells or other hells.” For the upper-class elite, punch houses were a definite ‘no go’.

By the early decades of the 19th century this public drunkenness and violence was so pervasive in the three colonial cities as well as smaller outposts across the country that the authorities grew increasingly alarmed at the damage such behaviour was doing to the image of European and Christian superiority. Serial campaigns were launched. Multiple strategies tested. Workhouses were built, as were insane asylums. Forced religious conversion was tried out, so too was jail time. None was very successful and the problem of European drunkenness remained forever an embarrassing black spot on the rulers publicly promoted sense of moral superiority.

Though alcohol abuse remained a problem among the British, over time the raw violence of the punch house gave way to other forms of entertainment. Musical evenings, card games and regularly scheduled visits to other European homes were popular among the ‘better’ classes. The rowdier types (i.e. drunken sailors high on Punch) were drawn to disrupting dramas and causing havoc at dramatic performance at a number of theatres that began to pop up across Bombay.

Bombay’s first theatre opened in 1776, situated on a space known as ‘The Green’ surrounded by other official buildings. The Bombay Theatre, as it was christened, catered to officials and their families and staged performances by amateur drama enthusiasts from among the European community. It experienced a difficult life through the early years of its existence and ultimately stood shuttered and unused for many. It was eventually bought by the city’s post prominent businessman, Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, a Parsi opium and shipping magnate, who never bothered to reopen it.

By the mid 1840s, the city was wealthy and large enough (thanks in large part to the illegal trade of opium smuggling) to demand better entertainment. Wealthy Indians, again mostly Parsis, championed theatre building as an important part of their civic duty which grew to include funding public charities, colleges and museums. The Grant Road Theatre opened on the northern edge of the city in 1846, at the time, quite a distance from the Fort area inhabited by the elites of the Company. Though opened with an eye on that market few English found the prospect of travelling into underdeveloped outer suburbs, where hygiene and other surprises lay in wait, attractive. Very quickly the financiers opened the halls to local artists who staged plays in Bombay’s most widely spoken languages, Gujarati, Urdu and Hindi.

Somnath Gupt, who wrote a history of Parsi theatre summed up the transition this way. “As long as it was patronized by the governor and high-level officials, the theatre was frequented by people of good family. Because of the location on Grant Road, however, their attendance decreased. Some Christian preachers also opposed the theatre as depraved and immoral. The Oriental Christian Spectator was chief among those newspapers that wrote in opposition to Hindu drama. In consequence, the theatre was attended by sailors from trading ships, soldiers and traders. A low class public came and made the theatre foul-smelling with their smoking. The performances began to start late, and etiquette deteriorated. Drunken sailors and soldiers behaved rudely with the women. It began to be necessary to bring in the police to keep order. This audience was…inherited by the Parsi theatre.”[1]

The Grant Road Theatre hosted international troupes enroute to and from Australia when they showed up but the 1850s saw Parsi-owned theatrical troupes mushroom to fill the supply of plays, actors and audiences. Based on the European proscenium-style theatre that featured a huge arch over the stage as a frame for the action, the Parsis saw the theatre as a way to both entertain and educate Bombay’s growing middle class.

What quickly became known as Parsi theatre was an instant hit. The plays set the imagination of Bombay-ites on fire. Many of the plays were wildly popular, running to packed houses night after night for years on end. A whole new class of Parsi actors, playwrights, directors, composers and producers grew up, many of whom moved seamlessly into the film world in the early 20th century. Many companies toured the countryside, not just around Bombay but to far flung parts of the interior and even to places as far away as Sumatra, Malaya, Burma and Ceylon. Drawing on local talent and tales from Hindu, Islamic and Persian epics, Parsi theatre became a uniquely Indian and lively form of entertainment many aspects of which—song, dance, bawdy humor, melodrama—were directly absorbed by the subcontinent’s early film makers.

Along with the companies and cohort of professional players, more theatres were built with names like the Elphinstone, Gaiety, Novelty and Tivoli. The staging of dramas was by the 1870s and 80s a huge part of Bombay’s entertainment scene. Jamshedji Framji Madan “the Parsi actor-turned-wine merchant-turned owner of the largest chain of theatres and cinemas in India in the first three decades of the 20th century”[2] exemplifies the central role the Parsi community played not just in whetting the Indian appetite for staged comedic and dramatic entertainment in purpose built buildings, but of leading the transition from Parsi Theatre to what would become one of the most consequential film industries the world has ever seen.

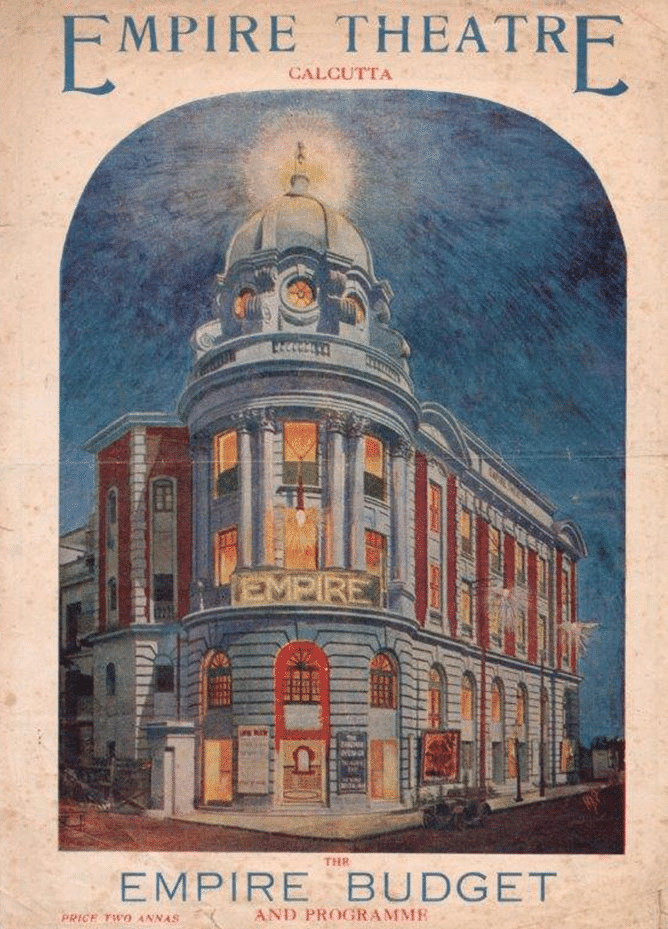

Madan started his career in the theatre first as an actor but he made a considerable fortune in y securing large contracts to provision British troops with the wine that the governing classes so condemned for corrupting Her Majesty’s troops. Sensing greater opportunities in the capital of British India, Calcutta, and loaded with money from his wine-provisioning business, Madan in 1902 set up a diversified business group, J.F Madan & Co., with interests in everything from insurance to film equipment and real estate. He also began buying up Calcutta theatres (the Alfred and the Corinthian) where playwrights including Agha Hashr Kashmiri, aka India’s Shakespeare, plied their trade. Kashmiri, though from Banaras, moved to Lahore in his later years where he also wrote for films, an early example of the cross fertilisation of cinematic talent between India and what would soon become Pakistan.

Immediately after arriving in Calcutta, he set up the “Elphinstone Bioscope Company and began showing films in tents on the Maidan before opening the first dedicated movie house in Calcutta, the Elphinstone Picture Palace.”[3] The venue not only was Calcutta’s and India’s first dedicated movie hall but marked the beginning of India’s first cinema hall chain. In 1917 his company, Far Eastern Films, partnered with Maurice Bandman, an American entertainment magnate based in Calcutta to distribute foreign films in India. “In 1917 his company Madan’s Far Eastern Films joined forces with Bandmann to form the Excelsior Cinematograph Syndicate dedicated to distributing films as well as owning and managing a chain of cinemas. In 1919 Madan, like Bandmann, floated a public company, Madan Theatres Ltd, which incorporated the other companies. It was this company that formed the basis of the remarkable growth of the Madan empire.” Madan’s multiple interests in theatre and commerce led him to producing his own films, including the first commercial length feature in Bengali, Bilwamangal (1918).

Madan’s strong commercial eye recognized that the medium would need its own venues and screening halls, rather than relying on established theatres. By 1919 the Madan Theatres Limited was in business and set to become India’s largest integrated film production-distribution-exhibition company with assets located not just across India but in Ceylon and Burma as well. Madan issued shares that generated Rs. 10 million and through effective management practices was able to procure a huge number of theatres across South and SE Asia. Though film making was picking up steam in India, the vast majority of films shown were foreign. In 1926 only 15% of films were Indian. 85% were foreign, mostly American, movies. By partnering with the French company Pathé Madan’s theatres were to a significant degree responsible for creating an audience for American and European films in India by importing and screening Hollywood films, such as the Perils of Pauline, The Mark of Zorro and Quo Vadis.

By the mid-1920s Madan controlled half of all revenues from the Indian box office and owned 127 movie houses. His hiring of foreign directors such as the Italian, Eugenio De Liguoro who directed 6 films for Madan Theatres, gave many of his films a sheen of expertise and craft that was not yet visible within local ranks. In essence, Madan had monopolised India’s nascent film industry.

**

The Lumiere brothers may not have understood the commercial viability of their inventions but it seemed that many Indians did. The great colonial cities of Bombay and Calcutta both quadrupled in size between 1850 and 1900 to be home for nearly 1 million people. Bombay and Calcutta were now world cities. It was not surprising that this most modern and hypnotic of new technologies would catch on in places like this. But Bombay, Calcutta and Madras were not alone. Far to the West, on the far frontier of British India another city was starting to make waves in the movie world too.

[1] Hansen, Kathryn. (Translator) 2001, “The Parsi Theatre: Its Origins and Development (Pt 2).Pdf.”

[2] Balme, Christopher. 2015. “Managing Theatre and Cinema in Colonial India: Maurice E. Bandmann, J.F. Madan and the War Films’ Controversy.” Popular Entertainment Studies 6: 6–21.

[3] Ibid.