Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

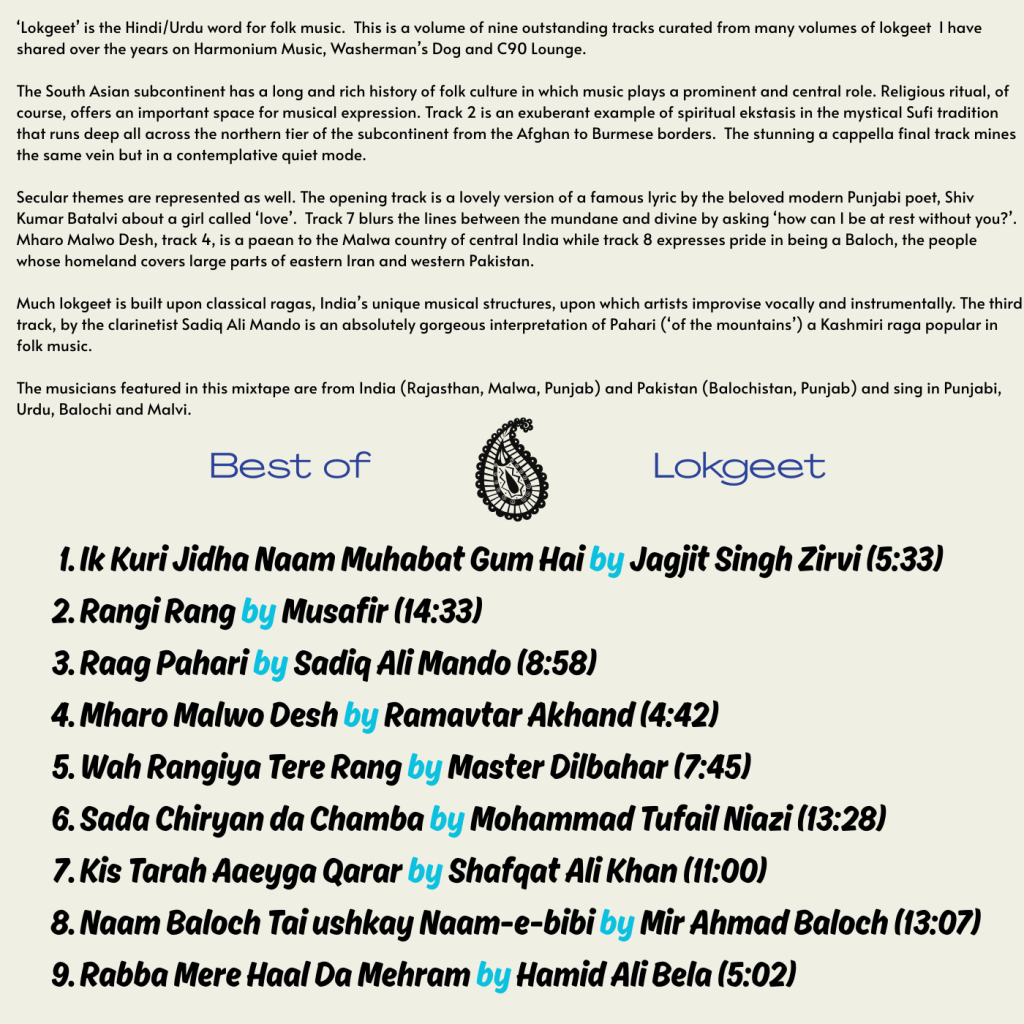

Mughal Stories

From day to day, experts present books to the emperor who hears every book from beginning to end. Every day he marks the spot where they have reached with his pearl-strewing pen. He does not tire of hearing a book again and again, but listens with great interest. The Akhlaq-i-Nasiri by Tusi, the Kimiya-yi-sa’adat by Ghazzali, the Gulistan by Sa’di, the Masnavi-i-ma’navi by Rumi, the Shahnama by Firdausi, the khamsa of Shaikh Nizami, the kulliyats of Amir Khusrau and Maula Jami, the divans of Khaqani, Anvari and other history books are read out to him. He rewards the readers with gold and silver according to the number of pages read.

It was between the 9th and 19th centuries when north India was ruled by a series of Muslim sultans that Lahore reached its cultural apogee. And especially under the Mughals who built India into the medieval world’s grandest empire. Akbar, the greatest of all the Mughal emperors of India loved books and stories. The snippet above, from his biographer Abul Fazl, is a fascinating glimpse into the cultured atmosphere that permeated the courts of the ruling elite of northern India. The royal library, Abul Fazl proudly noted, included books written in Hindavi (early Hindustani), Greek, Persian, Arabic and Kashmiri. Akbar’s sons and grandsons and many of his senior nobles continued to add to the library, composing their own works but also drawing to the great darbar (court) of Lahore the greatest talents from all across India, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and even as far away as Iraq.

The Mughals looked to Persia for their notions of culture and gave pride of place not just to the Persian language but to the great poets and thinkers of Iran. And it was from Persia that many of the grand stories they loved so much and which they adopted and were absorbed into Indian culture first came. The elites of northern Indian during this period adopted a number of Persian poetic and literary forms in which they preserved their histories, but also stories, poems and philosophies.

Several of these forms, especially the qasida, which was a poem in praise of the monarch, remained a novelty of the darbar and did not influence broader society, but several others did. Chief among these was the qissa, an extended poem that combined elements of moral and linguistic instruction as well as entertainment. The subject matter were stories of military valour, spiritual attainment, love and romance. The Mughals, especially Akbar and his son Jahangir enjoyed the qissa Dastan-i-Amir Hamza which relates at great length and with vivid imagination the fantastic adventures of the Prophet Mohammad’s uncle Hamza. So much did Akbar appreciate this work that he commissioned a massive project to illustrate the entire epic. Completed over a period of 14 years (1562-77) the final product included 1400 full page miniature paintings and was housed in 14 volumes.

Qissas were not just stories but in the control of a good narrator, complete one-man performances/ shows. Some of the royal qissa-khawans (story tellers) are recorded as demonstrating all manner of expressions, body movements and vocal tones in their telling, sometimes even transforming themselves, in the words of one critic of Lucknow, into tasvirs (pictures). Thus, introducing for the first time into Lahore the concept of moving pictures! Akbar so loved the story that several times he is described as telling and acting out the qissa himself in front of courtiers and guests. When Delhi was sacked by the Afghan Nadir Shah in 1739 the reigning emperor Muhammad Shah pleaded that after the peacock throne what he most desired to be returned to him was Akbar’s Hamzanama which had illustrations ‘beyond imagination’.

The critics of the day stressed both telling and listening to stories were beneficial to the soul with some claiming that in the cosmic order of beings, poets and storytellers were ranked second, right behind Prophets and before Emperors! Though this is undoubtedly a minority view, the best qissa-khawans were indeed highly esteemed.

In 1617, Emperor Jahangir, son of Akbar the Great, recorded the following event:

Mulla Asad the storyteller, one of the servants of Mirza Ghazi, came in those same days from Thatta and waited on me. Since he was skilled in transmitted accounts and sweet tales, and was good in his expression, I was struck with his company, and made him happy with the title of Mahzuz Khan. I gave him 1000 rupees, a robe of honor, a horse, an elephant in chains, and a palanquin. After a few days I gave the order for him to be weighed against rupees, and his weight came up to 4,400 rupees. He was honored with a mansab of 200 persons, and 20 horse. I ordered that he should always be present at the gatherings for a chat [gap].

It was under the reign, and patronage of Jahangir that Lahore became the favoured city of the Mughals. The emperor is remembered for ruling over a stable and prosperous Empire and for patronizing painting, poetry and architecture. A man of artistic inclinations it was during this time that story forms like masnavi which told of current events and wonderful victories and ghazal a short romantic-mystical form of poetry superseded other forms of literature. The ghazal in particular was championed by Jahangir and his son and successor, Shahjahan.

The ghazal both facilitated a large appreciation of poetry outside the circles of the aristocracy, among people of all walks of life, and began to be composed and recited in all sorts of settings including by women, in private homes, in public houses and in competitions. The masnavi quickly declined because compared to the ghazal it was a bit lengthy and rather tedious. The ghazal on the other hand, was snappy, called for clever word play and rarely ran more than a few verses. Mushaira, poetry recitations that centred around the ghazal, became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Lahore during this period.

Many tales are told of courtly mushaira presided over by the Emperor who believed that when expertly delivered, a ghazal was full of magical power.

One night a singer by the name of Sayyid Shah was performing for the Emperor and impersonated an ecstatic state (sama). Jahangir questioned the meaning of one line from the ghazal

Every community has its right way, creed and prayer

I turn to pray towards him with his cap awry

From the audience the royal seal engraver, one Mulla Ali gave an explanation of the line which was written by Amir Khusrau and which his father had taught him. As soon as he finished telling the story, Mulla Ali collapsed and despite the best efforts of the royal physicians to revive him, passed away.

Of course, this literary world of elaborate illustrated tomes, royal qisse and the like was not uniquely Punjabi. Rather it was the literary province of the elite and as such, familiar to most urban literate North Indians. But the mass of people was not literate and had no access to the libraries, the texts, treatises and poets of the nobility. And yet beyond the forts and palaces and even beyond the urban areas of Mughal India there pulsated a great tradition of storytelling that influenced the emergence of films in the early 20th century.

To name all of the genres of Punjabi storytelling would be nearly impossible. In addition to qissa and ghazal there were afsane (stories), dastan (heroic tales), latifa (jokes), katha (Puranic stories), naat (poetry in praise of the Prophet), kafi (sufi poems), boliyan (musical couplets sung by women), dhadhi, kirtan, bhajan, swang, sangit, nautanki , marsiya, mo’jizat kahanis (miracle stories of Shi’a Muslims), mahavara (proverbs) and so on.

These forms of storytelling were a part of everyday life for the people of Lahore and the Punjab. Though they may never have seen the beautiful courtly books produced by the Emperors, the characters, plotlines and themes were deeply embedded in the consciousness and culture of common folk.

One story in particular, Heer Ranjha, based on the Arabic classic Laila Majnun, was especially beloved by Punjabis. Compiled originally in the time of Akbar by a storyteller named Damodar Gulati, Heer Ranjha tells the story of a beautiful girl, Heer, who is wooed by a flute-playing handsome young man Ranjha. Rejected by Heer’s family because he belongs to a rival Punjabi clan, Ranjha turns toward a spiritual path. He spends time in Tilla Jogian, the premier centre of Hindu ascetism in the medieval period, and becomes a powerful kanpatha (pierced ear) jogi. His identity is uncovered by Heer’s friends who convince her to run away with him which ends badly with the death of both lovers.

The tale is the greatest of the many similar legends known as tragic love stories, the speciality of Punjab. Sohni Mahiwal, Sassi Pannu and Dhola Bhatti are taken from the same tradition and have been told, acted and sung to rapt audiences for centuries. Stories such as these and others, like Anarkali, whether recorded in royal tomes or told under a tree by a wondering minstrel formed the foundational inspiration for Lahore’s movie makers. By 1932, just four years after the Lahore produced its first film, Heer Ranjha had already been made into a movie four times!

Performing Arts

Though the earliest Punjabi stories were written down during the Indus Valley civilization, once Harappa and the other cities were abandoned, India would not use writing again until the rule of the emperor Asoka, more than 1500 years later.

The Vedas were memorised and passed on word for word from generation to generation through a caste of priests, the Brahmins. And though many of the later Buddhist tales and eventually, even the Mahabharata and Ramayana were put into written form, writing, reading and access to these skills were confined to the very thinnest layer of elite society. The stories of Punjab survived because they were remembered, retold, performed on stages, recited in poems, acted out in the streets and reimagined with each generation. This oral and physical transmission, this retelling and telling again, kept the stories fresh and alive, changing, not only depending on who was doing the dancing or singing but whether the context was spiritual, secular, public or private.

As with its oral and written literature, Punjab is likewise blessed with a huge variety of musical styles and musician groups. Broadly referred to by the public as mirasi, the society of hereditary Punjabi musicians is complex, and highly differentiated. Though musicians, singers and dancers were uniformly relegated to the outer limits of the caste and class system they played an important, even essential role in Punjabi society. They were the repositories of significant parts of family, folk, clan culture and history. When the movies arrived, the mirasi provided many of the musicians, dancers, singers and composers of what more than any other single trait exemplifies Pakistani/Indian popular movies, the song.

Certain groups of singers have had a direct and enduring connection with the film industry. The dhadhis, wandering minstrels and balladeers who trace their lineage back to the times of Akbar the Great, were particularly active in Punjab. Accompanying themselves on an hourglass-shaped hand drum (dhadh) and a variety of bowed instruments, dhadis specialised in singing heroic tales (var) of local chieftains, especially Sikh rajas ,as well as the tragic love tales such as Heer Ranjha and Sohni Mahiwal. Qawwals, who are sometimes considered part of the dhadhi tradition, were associated with the Sufi shrines and sing an intense trance (sama) inducing music that is so identified with South Asian Islamic practice. Qawwali was a form that was quickly picked up by film makers who inserted it into scenes as light relief or as a sonic representation of an Islamic character or theme.

Also associated with spiritual singing were a class of Muslim singers known as rubabis (after the Afghan stringed lute, rubab). The Sikh gurus employed rubabis to sing kirtans and shabad, essentially the sayings of the various Sikh gurus sung in their temples (gurdwara) as part of Sikh worship. These musicians had respected musical pedigrees and were expert on the rubab, harmonium, drums and other instruments. Being largely a Muslim group, most moved to Pakistan after 1947 and several played critical, pioneering roles as musical directors in the film world that grew up in Lahore.

The brass wedding bands that became an urban phenomenon in north India in the 19th century drew their members from yet another group of hereditary musicians known variously as Mazhabi (if they were Sikh), Musalli (if they were Muslim) and Valmiki (if they were Hindu). These musicians provided services including acting as town criers and news readers. They would make community announcements while beating their drums and playing their horns and clarinets. During festivals and celebrations they entertained people from their vast repertoire of religious and secular songs. As the forms of entertainment changed in the 20th century and especially when sound and music were incorporated into movies in the 1930s, these skilled players formed the backbone of the studio orchestras that produced the amazing soundtracks of the films.

In addition to singers and musicians a universe of street performers, actors and magicians made up part of the Punjabi landscape as well. There were bazigaars (acrobats and contortionists who also sang and acted), bhands (comics) who interrupted weddings and other events to make fun of prominent members of the family and their guests with quick jokes and bawdy repartee for small sums, madaars (jugglers and magicians) who with their magical powders and wands would make birds, eggs and even people disappear and reappear at will.

These groups performed publicly on the streets, in city squares or open fields and bazaars. At any fair (mela) or ‘urs’ (sufi celebration at a shrine) all of these and more would be part of the entertainment. Indian diplomat, Pran Neville, writes in his memoir of Lahore, “we had but to walk into the streets to be entertained by one or the other professional jugglers, madaris (magicians), baazigars (acrobats), bhands (jesters), animal and bird tamers, snake charmers, singers, not to mention the Chinese performers of gymnastic feats who would be out on their daily rounds.”[1] Like the mirasi, many of these castes of public entertainers found that the new film studios popping up in Lahore could be an unexpected source of livelihood.

If Parsi Theatre inspired the early film makers of Bombay, in Punjab other forms of theatre were just as important: swang, naqqali and nautanki. Each of these theatrical codes were common across the Punjabi countryside where performing troupes travelled and performed a rich variety of dramas.

The most important of the traditional theatres in Punjab was a form of nautanki known locally as swang. In essence swang which takes its name from the Sanskrit word for music (sangit) is informal folk opera. The production incorporates liberal portions of singing and dance and often all the parts are sung rather than spoken.

A performance would generally take place in an open part of a village where a local dignitary had invited the troupe to play. After a day of preparation during which the excitement built as stages were erected and children ran amok amidst the activity. The performers prepared by singing for hours with the heads facing downwards into the village’s wells, a practice that allowed them to improve their range and enhance their projection. The actual performance would finally begin late in the evening and continue till the early hours of the morning. If the plot was a long one this would continue over a number of evenings.

Audience participation–hissing, shouting, calling out requests for songs or jokes to be repeated–was expected and happily accommodated. The performers were masterful singers who had to project their voices over the audience noise and often compete against a rival troupe performing in another part of the village. It was said that some of the best singers could be heard more than a mile away. One only needs to listen to the resounding voice of Noor Jehan, Pakistan’s Queen of Melody, and one of the greatest film singers of the subcontinent, to get a sense of the amazing power of these traditional singers.

Long before Nargis played Radha in Mother India (1957) or Prithviraj Kapoor played Akbar in Mughal-e-Azam (1960) these open-air travelling opera companies were laying the essential template of and sketching out the iconic roles for South Asian popular cinema.

The City as a Story

Lahore, the cultural capital of the greater Punjab region was itself was a city of a million tales. In many ways Lahore, a city so fabled for so long, was the most famous of Punjab’s myriad stories.

The origins of Lahore stretch back to one of the two foundational epics of Hinduism, the Ramayana. In a storyline familiar to all movie lovers in South Asia, we are told that Sita, Rama’s wife and a goddess in her own right, becomes pregnant making her jealous husband, Rama, question her fidelity. Falsely accusing her of adultery, Rama turns Sita out of the house. Deep in a forest Sita gives birth to twin boys, Lav and Kush, whom she raises with great love and devotion. In a dramatic twist of Fate, years later, the boys are reunited with their father whom they have never met. They take him into the forest to meet their mother. Ram is stunned and realises his mistake but despite Rama’s protestations and desperate apologies, Sita is swallowed up by the earth and returned to the Heavens. Rama goes on to rule his kingdom with his two sons by his side in a Golden Era of peace and stability. When the time comes, he sets Lav and Kush up in the far West of his country where they establish themselves in two cities. Kush in Kasur, 52 km southeast of Lahore on the Indian border, and Lav in Lavapuri, modern Lahore, where even today, inside the fort of Lahore, there is still a small temple dedicated to this son of Lord Rama.

Despite its hoary Hindu roots, and being described as early as 300 BCE by the Greek historian Megasthenes as a place ‘of great culture and charm’, Lahore’s greatest glory was experienced when it was the capital of various Muslim sultanates and states. Throughout the medieval period when northern India was ruled by a succession of ethnic Turkish rulers who promoted a heavily Persianised culture, Lahore was a city of prime strategic, commercial and cultural significance. And despite its oppressive summer heat a reputation of luxury, elegance and sophistication attached to the city. Its guilds and craftsmen were heralded throughout the region and beyond; its poets, some of the most beloved, even in Persia. Like a handful of other cities around the world—modern Paris and New York for example—Lahore has developed a special atmosphere which has caused both natives and visitors to fall in love with it. Way back in the 12th century, Masud ibn Said al Salman one of the city’s most popular poets found himself imprisoned far from his home city for pissing off one of the city’s rulers. Pining away in his cell he wrote a lamentation.

Lahore my love… How are you?

Without your radiant sun, oh How are you?

Your darling child was torn away from you

With sighs, laments and cries, woe! How are you?

Each of the four great Mughals (Akbar, Jahangir, Shahjahan and Aurangzeb) did their bit to build, extend and refurbish the city. Along with Agra and Delhi and for a while Fatehpur Sikri, Lahore served for years at a time as the Imperial capital and was heavily fortified as a military hub. As it enjoyed the presence of the Emperor himself, artists, administrators, philosophers and emissaries hailing from all across the world came to Lahore to live, seek patronage and practice their speciality.

Poets such as ‘Urfi’ of Iran made Lahore their home finding the relatively tolerant and inclusive atmosphere a delicious change from the claustrophobic Shi’a Islam of his home country. He and other poets employed by the durbar [court] produced sublime poems which were sometimes reproduced on paper reputed to be as delicate and as thin as butterfly wings. Artisans brought their skills and looms to the royal city which by the 16th century had an international reputation for producing exquisite silken carpets which, in the words of one historian, made “the carpets made at Kirman in the manufactory of the kings of Iran, look like coarse” rugs.

The painters who made Lahore their home—both immigrants from Iran and the hills of Punjab and Kashmir, as well as natives—brought glory and awe to the city and its rulers. Ibrahim Lahori and Kalu Lahori, two painters in the court of Akbar illustrated a book called Darabnama (The Story of Darab) which set out the exploits of the young Akbar, sometimes in fantastic detail, just after he had decided to leave his new purpose-built capital, Fatehpur Sikri, to take up residence in Lahore. Their miniatures brought to life the Persian text which told wild tales of dragons swallowing both horses and their riders in one awesome gulp, as well as radical illustrations of naked humans which according to art historians were never before so accurately depicted by Indian artists. The Darabnama which is recorded as being one of the emperor’s favourite story books also depicts scenes from courtly life such as Akbar being praised and honoured by rulers from other parts of the world and India. Ibrahim Lahori along with miniaturists like Madhu Khurd are credited with bringing a fresh and naturalistic realism to portraiture. It was in Lahore-produced books like the Darabnama that for the first time individuals with all their physical quirks—bulging pot bellies, monobrows, turban styles—could be identified as real historical individuals.

The city’s countless mosques and Sufi dargah (tombs) honouring Lahore’s many saints and pirs are not just revered places of devotion but subjects of and characters in stories filled with miracles and magic that are still told today. The city’s storied inner walled city dominated by the domes of the Jam’a masjid but filled with hundreds of other havelis (mansions), shrines, tombs, pleasure palaces and gardens are themselves characters in the various storylines. How many poems, songs, operas and movies, including made in Hollywood, include the name Shalimar—those famous Mughal-era gardens of Lahore?

Probably the most famous of Lahore’s many stories and one that has been retold in film in both Pakistan and India many times, is that of Anarkali. Like all tales that have been passed down through generations this one has several different tellings but the most famous and popular one is the tragic one.

One day a Persian trader came to Lahore for business and brought with him members of his family. In his caravan was his beautiful pink complexioned daughter Nadira also known as Sharf un-Nissa. Her beauty stunned the bazaars of Lahore and word quickly reached the Emperor himself that there was a woman as splendidly gorgeous as a pomegranate seed in his city. He summoned the merchant to his court and upon seeing the young woman fell immediately in love with her graceful charm. The young woman’s father was only too pleased to accede to the great Mughal’s request for Nadira to be allowed to join the royal harem.

Much to the chagrin of his wives and other concubines Akbar seemed completely fixated upon the beautiful Iranian girl who was rechristened Anarkali (pomegranate seed) by the King himself. The only time she was not by his side was when he was away from Lahore, conquering yet more lands and expanding the glory of his family and empire. And so it happened when Akbar was leading his armies in a campaign in central India, Anarkali and the crown prince, Salim, later to rule as Jahangir, developed an intimate relationship. The gossip hit the bazaars and everyone spoke of how much the two loved each other. Salim it was said was ready even to renounce his right to the throne of India for a life with Anarkali.

When Akbar returned to Lahore he called for Anarkali but immediately sensed something different in the way she approached him. ‘What is the matter,’ he cooed but she resisted his embrace and made an excuse to retire to her chambers as swiftly as possible. Akbar was upset and soon livid when his spies and courtiers informed him of the fool Anarkali had made of him during his absence. ‘The bazaar is echoing with jokes that say Your Highness is too old to water such a lovely tree as Anakali’.

The next day Anarkali was summoned to the Emperor’s chambers. ‘Is what I am told true? That you love Salim more than me?’

Anarkali tried to demur but the wizened old ruler knew a lie when it was uttered no matter how lovely the lips that spoke it.

He sent his favourite concubine back to the harem and then called his chief wazir and instructed him to arrest Anarkali before the night was through. ‘You should bury the witch alive and leave no marking of her cursed tomb’.

In the years that followed Lahore was abuzz with rumours and theories of what happened to Anarkali. Salim was depressed as she was nowhere to be seen. Had she been banished back to Iran?

Eventually the old Mughal died and Salim ascended the jewel encrusted throne of Lahore. One of his first acts was to build a simple tomb on the spot where Anarkali had been so heartlessly murdered. Inscribed upon the tomb is a couplet from the love-lorn Jahangir himself, If I could behold my beloved only once, I would remain thankful to Allah till doomsday

[1] Pran Neville. Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. (New Delhi: HarperCollins, 1997), 60.

Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

Rivers and Stories

His eyes might there command whatever stood

City of old or modern fame, the seat

Of mightiest empire, from the destined walls

Of Cambalu, seat of Cathian Can,

And Samarcand by Oxus, Temir’s throne,

To Paquin of Sinaen Kings, and thence

To Agra and Lahore of Great Mogul….

(Paradise Lost XI 385-91. John Milton)

Fourteen hundred kilometres due north of Bombay and seventeen hundred kilometres to the northwest of Calcutta, sprawled across the flat northwest plains, lay the fabled city of Lahore. The city, erstwhile capital of not just the Mughals but numerous Afghan, Arab, Turk and Hindu kingdoms, had a reputation that extended across oceans, continents and time itself. Lahore was mentioned in Egyptian texts and visited by travellers and adventurers from China and Arabia in the early centuries of the current era, all of whom valorised the river city as a place of incredible wealth, luxury and refined taste. Elizabethan poets and dramatists including Milton and Dryden, fascinated by the contemporary accounts of adventurers from France and Italy imagined Lahore to be one of the grandest cities ever constructed by humans. Even in the late 19th century, the Orientalist opera Le Roi de Lahore (The King of Lahore) by French composer Jules Massanet, ran to full houses and ecstatic reviews all across Europe and North America. It’s bungled-up quasi-historical plot, set in the 11th century, had Lahore ruled by a ‘Hindoo’ raja named Alim (a Muslim name!) who tries to rally his people to stop the Muslim invaders. Almost forgotten today, Le Roi de Lahore was able to succeed simply by playing on the city’s name, which more than any other conjured up the mysterious exotic Orient in the minds of 19th century Europeans.

Compared to Bombay or Calcutta, Lahore was a seeming backwater. It possessed none of the attributes of the sparkling imperial cities. Where Bombay was new and young, Lahore was ancient. Where Calcutta was the modern power centre of India, Lahore was the sometime capital of the recently vanquished House of Babur. The new colonial metropolises looked outward, beyond India, to the future. Lahore and its walled ‘inner city’ seemed to be the perfect symbol of an insular and irrelevant past.

Far from the coasts, a distant outpost of Empire, there was nothing about Lahore that would suggest that movies, this most modern and technologically complex of entertainments, would take root here. In the early days (1900-1935) films were produced in all sorts of town across the subcontinent. Hyderabad, Kholapur, Coimbatore, Salem and even Gaya, reputedly the site of where Siddhartha Gautama meditated under a bodhi tree on his way to becoming, the Buddha. All had film production units, though almost all fell by the wayside after one or two outings.

Movie making was a cottage industry of sorts and anyone with a story and some basic equipment could shoot a short film. But as the audience for movies grew and with it a demand for meaningful and quality content (there were only so many wrestling matches and train arrivals you could stomach), production became concentrated in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. With the possible exception of the Prabhat Film Company, initially based in Kholapur but by 1933 centred in Poona (Pune), and which over a short life of less than 30 years produced only 45 films, Lahore was the only non-colonial city in South Asia to produce films of high quality, significant volume, in multiple languages over an extended period. And which continues to do so.

Why Lahore?

While Bombay, Madras and Calcutta had the location and access to new forms of capital and technology, the one thing they didn’t have much of prior to the arrival of the British was stories, the most ancient and beloved form of human entertainment. At heart, movies are nothing more than the most dramatic way of telling stories humans have yet invented. And prior to the arrival of Europeans, the three Imperial cities of India had little history. It was the British who conceived and built the cities; in essence their histories are inseparable from the history of the British Raj. This is not to suggest that the countryside around what became the three great Presidency cities was some terra nullius, devoid of human settlement and imagination. The islands of Bombay had been part of various kingdoms stretching back to prehistory and even under the Mauryas a regional centre of learning and religion. Various Hindu and Muslim dynasts had controlled the islands and, the settlements along the coast had well established links with far away Egypt. But by the time the English took possession of the islands they had lost any significant political or economic consequence. Prior to the East India Company there no Bombay.

So too with Calcutta and Madras. Though they were located in regions which had been part of ancient civilisations, both were mere villages that the English built into complex urban metropolises. Any stories that were told in these new cities had been brought in from outside. Bombay, Madras and Calcutta were blank canvases upon which was written a modern tale of interaction between Europeans and Indians. History was being created here. The past with its legends, myths and tales belonged to the countryside, the far away ‘interior’ from whence the cities residents had come to seek their fortunes.

Lahore, though, was different. It was not just ancient, it was still a vital, thriving city with a huge catalogue of stories stretching back to the very beginning of the Indian imagination. Like the other cities, Lahore attracted to it people from other parts of India but the stories they brought with them were absorbed into an already deep and luxurious sediment of fables, sagas and epics that remained every bit alive when the British arrived as they were when they were first told.

The Pakistani film industry, that which today some call Lollywood, is built more than anything upon this uniquely rich Punjabi culture. At the heart of which lies the immemorial city of Lahore. It’s worth taking a quick tour of this landscape to help us understand why the emergence of a movie industry here was not so much unlikely, as almost inevitable.

Treasure trove of tales

Punjab is the cradle of Indian civilisation. It was here in the land of five rivers (panj/5; ab/water) beyond which, in the words of Babur, Mughal India’s founding monarch, ‘everything is in the Hindustan way’, that the very story of India began.

Greater Punjab which includes all of the present day Province and State of Punjab in Pakistan and India, as well as parts of Khyber Pakhtunkwa, Rajasthan, Sindh, Haryana and Delhi, is home to one of the world’s richest, most variegated and dynamic of South Asia’s innumerable cultures. Peoples, and with them their stories, poems, music, gods, heroes, languages and ideas, have been flowing into the subcontinent via the Punjab since the earliest days of human settlement on the subcontinent. It is not in the least surprising that when the right historic moment arrived a lively and resilient cinema would be crafted from this treasure trove of material.

And to truly appreciate the deep roots of Pakistani films it is essential to have an understanding of the shared culture of language, song, theatre, poetry, storytelling and visual art that has distinguished this part of South Asia for millennia. It is from this profound tradition that Pakistani films initially took inspiration and upon which they continue to draw. And why, despite the many attempts to legislate against the industry, or even blow cinema halls up, Pakistanis keep making and watching movies.

Spies, scholars and antiquities

The good old man unfolds full many a tale,

That chills and turns his youthful audience pale,

Or full of glorious marvels, topics rich,

Exalts their fancies to intensest pitch.

Charles Masson

In 1832, while carrying out his undercover duties as a ‘news writer’ (spy) in the employ of the British East India Company, a certain Karamat Ali was taken by the recent arrival of a strange European in the bazaars of Kabul. Following from a distance he made mental notes of the character which he included in his next report to his control Mr. Claude Wade, British Political Agent in Ludhiana.

‘I would like to bring to your kind attention’ writes Karamat Ali in an undiscovered report, ‘the presence of an Englishman in the city. He keeps his hair (which is the colour of some of my countrymen who stain their beards with henna) cut close to his head. His eyes I have noted are the colour of a cat, by which I mean, grey and transparent. His beard is red as well. He appears to be a strong man as he has no horse or mule with him. His clothes are dusty from walking across the countryside and on top of his head he wears a cap made of green cloth. You may find it difficult to believe but he wears neither stockings nor shoes on his feet. I have learnt he carries with him some strange books, a compass and a device by which he reads the stars and thus makes his way from one place to the next. He answers to the name of Masson and speaks excellent Persian. I trust you will find this information helpful in your duties as Political Agent. Post Script. He could be mistaken for a faqir.’

Mr. Wade was well pleased with this information which he tucked away in the back of his mind. Over the next several years this mysterious Mr Masson continued to enter and exit official British communications like a phantom. Some reports had him pegged as an American physician from the backwoods of Kentucky. Others spoke of his brilliant command of Italian and that he was in fact a Frenchman. He popped up in Persia then Baluchistan; some reports detailed his convincing tales of journeys across Russia and the Caucasus.

But Afghanistan was where this strange morphing wanderer seemed most at home. He was reported to be interested in the history of some old earthen mounds outside of Kabul and had enlisted a number of the natives to assist him in his digging. Political Agent Wade kept tabs on Masson until finally three years after Karamat Ali’s report he wrote a letter to the wanderer with some shocking news. Over the years Wade had pieced together the mystery man’s history and in his letter he took great pleasure in letting Masson know about it.

‘I know who you are, Masson. And not just me. Calcutta is perfectly informed of your antecedents. The jig is up, old boy. You are not Charles Masson at all, sir. You are an Englishman and a traitor. Your true name is James Lewis born in London the son of a common brewer. You arrived in this ghastly country some dozen years ago as a private soldier in the Bengal European Artillery 1st Brigade, 3rd Troop.’

The letter which clearly made Masson panic went on to detail his history as a deserter from the Company ranks at Agra and the precarious position vis-a-vis his former employer he now occupied: he was due to be shot if apprehended. But Wade being a practical sort of man and a patriot had already received permission from his superiors to throw Masson a lifeline.

‘We’ve noted your excellent knowledge of several languages including Persian, French and Hindoostani. You also appear to be blessed with a natural ease in your interactions with the natives of the regions you have traversed. Your mind clearly, though not pointed in the proper direction, is sharp. In light of this and by way of making amends for your dereliction of duty and in recognition of the reality that the Tsar is intent on extending Russia’s influence into our Asiatic possessions, I offer you the following modest proposal.’

Wade informed Masson that if he would like to escape the firing-squad he would be wise to accept the Company’s offer to return to Kabul as its spy and to use his sharp mind, ears and eyes to keep Wade abreast of events in ‘lower Afghanistan and Kabul with special attention on the comings and goings of the tribesmen in support of Dost Mohammad but even more so the Russians.’

Mr Charles Masson of course agreed to Wade’s proposition and did (unhappily) return to Afghanistan as the Company’s ‘news writer.’ For several years, leading up to the invasion of the country by his compatriots in 1839, Masson filed detailed and insightful reports many of which cautioned against a British invasion. At the same time, he continued his archaeological digs on the outskirts of Kabul and beyond, wrote ponderous historical poems and engraved a couplet that included his name onto the majestic 55 metre high Buddhas of Bamiyan where it remained until the icons were blown up by the Taliban in 2001.

By the time he left the Company’s employ in 1838, Masson had ensured his place in history. Not so much as a spy or soldier but as a scholar. His archaeological digs around Kabul are now acknowledged as advancing the world’s understanding of ancient Afghanistan as well as its archaeological history. His work is still hailed as absolutely fundamental, especially his identification of Bagram as the ancient city of Alexandria Caucasum. Alexandria in the Caucasus while geographically inaccurate was indeed a city established by the Macedonian conqueror, Alexander, but one that history seemed to have assigned to legend. No one knew where exactly it was located which perhaps accounts for the faulty identification of the mountains where it was thought to have been located. Did it even exist?

By digging up tens of thousands of coins many with Greek script on one side and the Kharosthi script on the other, around the town of Bagram, north of Kabul, famous in more recent times as the site of the US Air Force’s major military post in Afghanistan, Masson identified the city as not only as one of the many ancient Alexandrias but shed new light on the Greco-Buddhist culture that dominated the area until the arrival of Islam. Indeed, Masson was instrumental in uncovering evidence of the spread of Buddhism into Central Asia from its Indian birthplace, as well as unearthing the names of several hitherto unknown monarchs of the region.

Masson returned to England in 1842 where he faded away, the only trace being the thousands of artefacts he dug from the Afghan dirt and transported back home and which are now on display in collections across the country. And though he is regarded as a pioneer of Afghan archaeology this rough and tumble shape shifting scholar-spy-poet is also credited with another landmark historical discovery.

Reflecting in 1842 on his initial desertion from the Company’s army in Agra and escape through the Punjab plains sixteen years earlier, Masson wrote,

A long march preceded our arrival at Hairpah (Harappa) through jangal of the closest description…Behind us was a large circular mound or eminence, and to the west was an irregular rocky height, crowned with remains of buildings, in fragments of walls, with niches, after the eastern manner…I examined the remains on the height, and found two circular perforated stones, affirmed to have been used as bangles, or arm rings, by a faqir of renown. He has also credit for having subsisted on earth and other unusual substances…The walls and towers of the castle are remarkably high, though, from having been deserted, they exhibit in some parts the ravages of time and decay.’ (Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan, and the Punjab 1842, pg 452-54)

Thus, within a few lines from an adventurer’s memoir the Western world hears the name Harappa for the first time. Harappa, of course, is the small town just 24 km west of the modern Pakistani city of Sahiwal where 95 years after Masson’s overnight camp, excavations lead to the uncovering of a large buried city, and ultimately one of the world’s oldest, most sophisticated and enigmatic urban societies.

Thirty years after Masson’s visit, British engineers engaged in building the rail line between Multan and Lahore discovered a trove of wonderfully hard but thin kiln-fired bricks lying just beneath the surface of the earth. The bricks, much to the engineers’ delight made the perfect beds upon which to lay the rails and tens of thousands of them were used and in fact remain in place even today. The bricks formed the ‘castle’ Masson described in his book. Scattered in and amongst the bricks, railway workers discovered a number of small soapstone seals, no larger than a large modern postage stamp, but exquisitely crafted. They were quaint, mysterious objects whose beauty and workmanship were beyond question but whose history and significance baffled the archaeologists. A few made their way into the British Museum where bearded antiquarians speculated they dated to a Buddhist past around the turn of the millennium. In 1921, a young Punjabi archaeologist and Sanskrit whiz, Daya Ram Sahni, did some initial excavating at Harappa for the Archaeological Survey of India. His report piqued the interest of the ASI’s Director, John Marshall, who authorised Sahni to undertake more systematic excavations.

To their amazement Sahni’s men uncovered an entire city laid out with gridded streets and communal buildings. Delicate, finely worked beads and bracelets emerged out of the Punjabi mud as well as further south in Mohenjo Daro in the Sindh region. Many of the artefacts, especially the seals, were marked what appears to be a script–lines, single or in close formation–squiggles and geometric designs. Despite the efforts of Sahni and others to decode the language, the lines remain one of antiquity’s great mysteries. But the archaeologists noted that the most extensive use of the language was visible on the seals and amulets which also featured a menagerie of beasts.

These seals depicted bulls with massive humps, rhinos, elephants, tigers and deer, sometimes with humans bowing before them, sometimes with the poor sods being attacked. Here was India’s first story. But what exactly is the plotline? What is the point of these images? Are they telling us about the spirit world or the world of markets and trade? Who are the heroes? Which ones are the demons and villains? If only we could make out that writing.

What seems clear is that the people of Harappa and other Indus Valley cities were not particular inclined to warfare and violence. Archaeologists have not found anything that suggests the people were massacred or that their cities were burned or destroyed in combat. Rather, the similar layout and construction of the houses, the lack of particularly large private dwellings together with those seals, which scholarly consensus suggests, were “probably used to close documents and mark packages of goods“, (they’ve been found as far away as Iraq) suggests early Punjabi life was relatively cooperative, civil, peaceful, prosperous and not very religious. There is little of the elaborate hierarchy of later Hindu India and relatively little evidence of great economic inequality.

Such readings of the Indus Valley story are speculative but not so far-fetched. However, the relatively tolerant, accepting, less heirarchical social structure that some scholars attribute to the people of the Indus Valley does echo, if ever so faintly, the Punjab which until the mid-19th century was renowned for its syncretic, less orthodox and unitary culture.

One thing that can be said without any doubt about the people of the Indus Valley is that these earliest of Punjabis had vivid imaginations. Of all the animals depicted on the seals the most common is what appears to be a unicorn, a cow like quadruped with a long pointy horn protruding out of its forehead.

This unique beast which we now associate with rainbows and 8 year old girls, was born in the Indus Valley but doesn’t seem to have survived in the post Harappan culture. Further west though, the unicorn went on to enjoy a glorious career as a symbol of chastity, the Incarnation of Christ, strength and true love. The one horned Punjabi horse/cow was and is so revered it graces the coats of arms of noble houses from the Czech Republic to England and is the subject of some of the most sublime works of European art and storytelling.

The cities, script, society and unicorns of the Indus Valley vanished from the Punjabi story about 1900 BC and would all but be forgotten for thousands of years. But an even richer series of chapters began to unfold around the same time. Nomads from the steppes of Central Asia came across the mountains with horses, powerful hallucinogens and a love of gambling. Over several centuries they herded their cattle and horses across the plains and between the Punjab’s many rivers. These nomads who called themselves Arya began to recite an elaborate series of poems that told tales of mighty gods and wily demons who provided instructions on how to sacrifice animals and conduct animal sacrifices. Like the American blues would millennia in the future, the Aryan poets bemoaned the addictions of gambling and intoxication.

Unlike the Harappans, the Vedic Punjabis left no cities or monuments. The only way we know them is through their stories—the Vedas—especially the Rg Veda, a song cycle of 1028 verses that was and continues to be passed down by people who took it upon themselves to memorize its every syllable, tone, character and subplot. Suddenly, around 4000 years ago, the Punjabi/Aryan/Vedic/Indian imagination erupts with the intensity, colour and wild swirlings of an acid trip.

The rivers of this land, the Rg Veda tell us, are not five but seven and the land is called Sapta Sindhu (seven rivers). Each one of them is identified by name and is in some way a geographic representation of a character in the grand Vedic story. Vyasa (Beas) is the great sage who divides the Vedas into parts and Askini (Chenab) is married to Daksha who is instructed by Brahma to create all living beings. One of the great Vedic sages Kashyap has a daughter Iravati (Ravi) and one day he asks the goddess Parvati to come to Kashmir to clean up its valleys which she does by becoming the river Vitasta (Jhelum). Saraswati, the goddess of arts and learning herself is a river that flows through the desert but eventually dries up leaving one of her tributaries, Sutdiri (Sutlej), to carry on and join with the others in the rushing Sindhu (Indus).

In these early Punjabi poems and narratives it’s easy to find the deepest roots of many of the outlines of what would one day depicted in the films made in Bombay and Lahore. Take for example the story of the lout who takes a swig of soma (a sort of pre-historic Vat 69) and with his mates tosses the dice onto the gambling mat. He laughs and carouses as his dutiful and kind wife watches silently. Eventually, but too late, the gambler realises his mistake. “I’ve driven my blameless wife away from me. My mother-in-law hates me and all my friends have deserted me. They have as much use for me as a decrepit old horse.”

His mother cries and tries to make him stop but he pushes her away. As the sun goes down, he starts his lament confessing that as soon as he thinks of the tumbling dice, he is off to the gambling dens with his male buddies. Like the drunken Talish in the 1957 film Saat Lakh, who sings the apologia, Yaaron mujhe muaff rakho, mein nashe main hun, [Friends, forgive me, I’m completely pissed] the Vedic gambler sings, “I can’t stop and all my friends desert me.” As the story comes to an end he collapses and dies. (Rg Veda 10:34). Very Lollywood!

The Aryans slowly moved eastward, leaving their beloved Sapta Sindhu behind to push into the northern plains watered by the Ganga and Yamuna rivers. Eventually Vedic religion as outlined in the Rg Veda was transformed into what we recognize as Hinduism and the central importance of Punjab to the Hindu story diminished somewhat. Which is not to say it was completely forgotten, as later epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata are filled with references to the places and people of Punjab.

This northwest corner of the subcontinent which was the reputed land of legendary wealth was coveted by other non-Indian empires. Persians, Greeks, Chinese, Mongols, Turks and Arabs and numerous waves of Afghan raiders came crashing through the Punjab on their way to the fabled riches of India. With each of these incursions came not just soldiers but new traditions, new ideas, new heroes and new villains.

During the period 500 BC-300 CE small fiefdoms and city states vied for control of the Punjab and more layers were added to the already rich three-millennia old culture. Taxila, 375 kms northwest of Lahore, became the most significant political and cultural centre of the region. It was here, the story goes, that the sage Vaishampayana (pupil of Vyasa) gave the original recital of the Mahabharata to king Janamejaya. The world’s longest narrative poem (100,000+ verses) the Mahabharata tells with fantastic imagination and a cast of thousands, the battle of various Punjabi tribes for supremacy.

Darius I of Persia, drawn to India for its supply of elephants, camels, gold and silk conquered Taxila in the mid 5th century BCE. By the 4th century Buddhist jataka tales (fables of the Buddha’s early incarnations) were speaking of Taxila as a mighty kingdom and centre of great learning. Indeed, it was around Taxila that Greeks who had ventured to the edge of India as part of Alexander’s victorious army, intermarried with local women and developed the unique and elegant Greek-Buddhist Gandhara, culture that added a distinctly European flavour to Indian culture and which Charles Masson did so much to illuminate.

Tales and narratives travelled in both directions, influencing the stories of Punjab but also taking Indian stories to the far corners of the world. The fable of Alexander and the Poisoned Maiden is one such Punjabi story that grew out of this mingling of Greeks and Indians. Though it is long forgotten in India the story was picked up and recorded by the Persians from whom it was passed to Arabs, Jews, and eventually Europeans who recorded it in Latin.

The astrologers of an Indian king warn him that a man named Alexander will one day try to conquer his kingdom and before he does, he will demand tribute of four gifts: a beautiful girl; a wise man able to reveal all of nature’s mysteries; a top notch physician and; a bottomless cup in which water is never heated when placed on fire.

When Alexander arrives in the kingdom, the king obliges in hopes of saving his kingdom. He selects a beautiful maiden whom all of Alexander’s emissaries agree is the most beautiful woman they have ever laid eyes on. Little did they know however, that the woman had been raised as a child by a snake and has been fed poison all her life, instead of milk. Alexander immediately falls in love and that night sleeps with her. However, the top notch physician is aware of the woman’s true nature and quickly slips Alexander a special herb that protects him from the girl’s poison. A grateful Alexander is able to enjoy sex with the woman but not die and he goes on to conquer the Indian king’s country.

Though his story does not exist in any Indian text its central character–a dangerous woman who in fact is a snake (nagina)–is a famous and recurring subject of many a horror film in both Pakistan and India.

Such fantastic stories pop up throughout the history of the region and are buried deep in the DNA of Punjab. We have stories of Buddha as a college boy at Taxila University as well as stories from Zoroastrian Iran. There is even a story told of how St. Thomas was sold into slavery to the king of Taxila by none other than Jesus himself but who manages to secure his freedom by raising the Punjabi king’s brother from the dead! A thousand years later the film makers of Lahore would tell a similar story in the cult horror classic Zinda Laash (Living Corpse).

Note: the letters from Karamat Ali to Charles Wade and related conversations are made up. However, the basics of the narrative are historically accurate.

Introduction

The bloody cataclysm of 1947 which resulted in the death and displacement of multiple millions of people, the destruction of an ancient city’s sense of community, the disruption of a vibrant economy and a fundamental reassessment of a people’s and city’s very meaning and identity seemed to signal, beyond any shadow of doubt, the end of Lahore’s emerging movie making dream.

Within a month of Roop Kishore’s escape and the razing of his sparkling new studio the guts were ripped out of the entire industry. The financers and producers, most of whom were at least ‘nominal’ Hindus’ like Shorey, many of the editors and writers of the city’s lively film press, actors, music director, playback singers, directors and countless Sikh and Hindu technicians—cameramen, editors, sound recordists and visual artists—fled. While most probably harboured hopes that ‘when things calm down’ they would return–‘maybe a few weeks, at most a month or two’– and pick up finishing the picture they were working on, all except a small handful never set foot in Lahore again. As it happened, Roop Kishore Shorey was one of the few who did. But we’ll get to that a bit later.

By the end of 1947 the writing was on the wall. The exciting glory days of making films in Lahore was over. The city’s movie refugees reconciled themselves to re-establishing themselves in Bombay, which except for the biggest names and most established stars turned out to be a struggle. Eventually some made it and went on to become rich. Even giants. Most found work, maybe even had a hit or three, but within a decade, they quietly faded away like the pages of the film magazines that once published their pictures.

Back in Lahore the remnant of the industry had other priorities: rebuilding their city, burying their dead, feeding and schooling their children. Making films seemed frivolous under the circumstances. And already questions were being raised by the mullahs, those who had championed the very idea of Pakistan as a thing, about whether there was a place for such a ridiculous, scandalous and even anti-Islamic thing as movies in the new country.

A number of Muslim actors, directors, producers singers and writers did leave Bombay and Calcutta and move to Lahore. But their number was small, especially in the early days. It is said that Mehboob Khan, one of India’s most revered directors, maker of Mother India, made a quick post Partition foray into Lahore to assess whether he should emigrate. “I need electricity to make films,” he is reported to have snorted upon his return to Bombay.

Yes, Noor Jehan, India’s most famous and beloved singing actress, ‘opted’ for Pakistan as did Manto, the incendiary writer, and a few other biggish names but obstacles and hurdles were so many that the idea of putting Lahore back on the film making map seemed the stuff of madmen. Manto drank himself to death, after spending most of his time in court fighting for artistic freedom.

One can empathise with their gloom. The dream had ended not only so abruptly, but too soon.

Films had been a part of Lahore’s life since at least the 1920s though one source claims that the Aziz Theatre in Shahi Mohalla was converted to a cinema in 1908. The city’s residents, especially the large number of students who attended Lahore’s many premier universities and colleges, were instant fans and supporters of the medium. Hollywood movies starring Mary Pickford, Hedy Lamar, Charlie Chaplain, Douglas Fairbanks and especially Rudolph Valentino were hugely popular. Rowdy Punjabi audiences were recognised (and most of the time appreciated) for their unabashed preference for action and romance pictures; by the late 1920s and early 30s the Northwest region of India was the number 1 film market outside of Bombay. The big production centers of Calcutta and Bombay made pictures that would appeal to the Punjabi and Muslim audience churning out Mughal era historicals and recreations of Arabic and Persian folk stories.

In the late 1920s a Bhatti Gate resident, Abdul Rashid Kardar, turned to making his own films. Filmed in open air along the banks of the Ravi river or amidst the city’s many medieval ruins, the films were well received even if by a tiny local audience. Wealthy businessmen and civic leaders started investing in the new technology. A high court judge invested Rs45,000 in a German Indian co-production called Prem Sanyas (The Light of Asia), a story of the Buddha, that has gone on to be claimed as a classic of world cinema.

When speaking and singing pictures became possible others jumped into the river. ‘Studios’ and production units popped up all over the place in Muslim Town, on McLeod Road, along Multan Road, and especially Laxmi Chowk. Lahore’s publishing industry sprang into action and began pumping out film magazines in English and Urdu from as early as the 1920s and 30s. Roop Kishore Shorey started making rip offs of American and Bombay action films some of which got fair notices. After a downturn in the mid-1930s by the early 1940s Lahore was fast developing into the B-movie capital of India. A source of talent and story lines (the number of Lahore or Punjab born and or educated actors, directors, producers, singers and writers who made and whose children and grandchildren continue to make Bombay the world leading industry it is, is too numerous to count) Lahore was what the Americans call a farm club. A place where talent was procured tested and then sent up to the big leagues in Calcutta and Bombay.

While the smart movies were made in Calcutta and the big productions came out of Bombay the filmmakers of Lahore in no way suffered from an inferiority complex. They prioritised quantity, action and speed. They prioritised fun. They made money, they drank, they swapped wives, they got divorced, they gambled and raced the horses. They travelled the world looking for money and even produced films for international markets.

But then the dark clouds of politics rolled in and poof—like the bomb in one of their action movies–the game was up.

Yet, it was in the bloody rubble of Lahore that the seeds of a new industry were born. Not just a minor player, but within a few decades, a booming national film industry. By 1970 Pakistan was the largest film producer in the Islamic world and the 4th largest (by volume) in the world. Without its old stars it produced several generations of superstars, actors, starlets, writers and singers, oh the singers. Not just Noor Jehan, but Mehnaz, Irene, Nahid and the Bengali bomb, Runa Laila. A lot of them went on to sing for Bollywood and still do (Atif, Adnan Sami, Ali Zafar, Rahat).

That Lahore would be a major world film centre is on the face of it improbable. It was far removed for the colonial power centers and indeed, is the only major south Asian movie city not based in a colonial city, that has survived and thrived. How weird is that? Especially, in such a hostile environment. In a land where official, political and religious biases have constantly been more of a threat than the erstwhile films of India which are forever being outlawed.

To understand this amazing, improbable story we have to start not with Roop Kishore Shorey staring into the ashes of his modern studio but go back in time to the very beginning.

Scenes from never-made Pakistani films [Number 1]

Film: Tabahi (Annihilation)

Released: June & July 1947

Starring: al Nasir, Vinod & Roop Kishore Shorey

A man stands by the side of the road staring into the smouldering skeleton of a large double storied building. He covers his nose with a blue silk handkerchief to keep the noxious, semi-sweet smell of burning nitrate at bay. The lenses of his round rimmed glasses reflect the flames that leap from room to room.

The camera pans back for a super wide shot and reveals behind him the apocalypse that everyone had been praying would never come playing out. The citizens of Lahore are moving hurriedly and fearfully towards the railway station. For once no one argues with the tonga walas who are demanding Rs100 to make the short journey. Bloated groups of people–women and children in the middle; wild-eyed men armed with swords, pistols, axes and lathis on the perimeters–move deliberately towards neighbourhoods where their co-religionists might give them safety. Hindus to Nisbet and Chamberlain Roads. Muslims to Mozang and Icchra. Sikhs want to make Amritsar or Delhi.

To the north, old Lahore is an inferno. The once rich markets and havelis of Shahalmi, one of Lahore’s mighty 13 gates is no more. Gangsters and politicians had banded together two days previous to raze the historic mohalla to the ground, killing hundreds of mostly Hindus. War chants echo in waves as lorries race by loaded with enraged men. “Khoon se lenge Pakistan!” “Har Har Mahadev.” For weeks the citizens of Punjab’s greatest city have heard that goondas from Amritsar have snuck into town to mock and shame their Muslim brothers to cleanse the city of all kafir. In response the Sikh leaders have mobilised their small armies of jathas in an all out war of revenge. Everyone knows that even the Lahore Relief Committee set up by some prominent Hindus is just a front for RSS militants more concerned with smuggling weapons to their frightened people than offering relief any sort of relief.

The days are unbearable. The early summer heat has maded the tar on the roads gooey. With the fires and explosions all across the city the temperature has never risen so high. Perhaps when the rains come all this madness with come to an end?

The staring man goes by the name of Roop Kishore Shorey. He turns away and falls into the backseat of an American sedan that has been idling for him. Inside an anxious driver guns the car down the road and yells out “Where to sahib? Lahore is no longer safe.”

Shorey doesn’t answer. Next to him fidgeting anxiously sits his friend, the music director Vinod, who just a few months earlier had completed his first score for the movie Khamosh Nigahein at the now destroyed Shorey Studio. Vinod shouts for the driver to turn the car, which was headed north toward the city and railway station, to the south. ‘Go to Walton Air field.’

At the airport the pair find Al Nasir, the debonair hero and recently licensed pilot, readying his tiny single prop plane for takeoff. “You know, I only have room for one of you,” Al Nasir says merrily, seemingly oblivious to the carnage in the city.

“Take him.” Vinod pushes a nearly catatonic Shorey forward. “I’ve got a family to worry about.”

“Thirty-four and still a bachelor! Who can believe it,” laughs Al Nasir. Sex and women were essential parts of the actor’s life. He’d just divorced the beautiful Meena and was now hot in pursuit of a number of other starlets in Lahore and Bombay.

Shorey embraces Vinod seemingly unwilling to let him go, but the music director untangles himself. “I’ll follow you soon. I’ll find you, don’t worry. My family must think I’m dead, I have to go.”

Vinod runs back to the car which speeds off toward the city.

Al Nasir gets in beside Shorey and notices that the producer’s normally pristine white shirt is grey with dust and ash. Sweat and tears have muddied the lenses of his expensive German spectacles. He smiles grimly at his friend and without waiting for approval from the tower taxis down the runway. Lifting off, the plane circles and climbs steadily through the heavy, smoky air. Shorey stares out of the window. The city of his birth, the city he loved, the city he was so determined would one day be as famous for its movies as Bombay, is now a medieval battleground. Fires, pillars of black smoke and crumbled buildings everywhere. Around the railway station a mini city has grown up. He can hear gun shots, There are army trucks at every chowk.

‘We’ll be back,’ Al Nasir, calls out. He’s still smiling. “Nehru and Jinnah and Gandhi will sort it out. This is Lahore after all. Let them call it Pakistan. It’s still India. In a few weeks everyone will get tired of blood and bombs and the public will want to see our movies and have fun again.”

The plane climbs higher and disappears into a dark grey cloud.