18 January 1990

What a rush at the airport. A huge group of Raiwindi[1]s was heading to Lahore from Karachi. It was a jumbo.

Wally met me in the drizzle at the airport and took me straight to the border. He’s pretty bummed out with the developments in the States. Berkeley has fucked him over the BULPIP directorship; hiring someone else and informing him that he was not even in the running for this year’s directorship. Wally takes these things very hard but I know I would too.

Got across to Amritsar in an Ambassador[2] which stopped every half kilometer or so due to ‘blockage’ in the fuel pump. An ansty Aussie shared the front seat with me. He was wired—shouting at the drunks, pissed off with having to pay Rs. 20 for the taxi and going on and on about missing concerts and plays back in London. Not the kind of travelling companion I want. We parted at the Railway Station.

I was greeted by 2 friends–rickshaw walas—from my last trip to Amritsar. Made a new one—a hustler who first told me there was no way I’d get a berth on the Amritsar-Howrah Mail tonight. He left and then came back after a brief interval. He suggested if I paid a little ‘chai pani’[3] I’d definitely get one. So, I paid Rs. 20 for the ticket clerk and Rs. 40 to my new friend for the luxury of a sleeper berth. A good deal. Rs. 220 for a 1879km journey.

I asked my rickshaw friends if he was a ‘gent’. Not the English term but a shortening of the word ‘agent’, used in these parts to refer to touts and fixers. “Yes”, they replied, “but an honest one. He’ll do what he says he will.” And he did.

I had asked if there were any bombings on the rails[4] these days.

They looked at me disappointingly. “This is written at the time of our birth. There is no changing it. Bombs or no bombs, when your number is up, it’s up.”

One of the rickshaw walas then broke into a parable.

“There once was a man. A mad camel got to chasing him and to escape the man jumped into a well. The camel sat outside the well and said to himself, ‘He’s got to come out one day and when he does I’ll bite him’. He settled down to wait. After a couple of days a poisonous snake slithered by and bit the camel. In an instant the camel was dead.

“The man in the well finally crawled up to have a look. He saw the camel lying bloated in the sun, rotting away. He triumphantly strode forward and gave the camel a mighty kick. His leg sunk deep into the rotting belly of the camel. The man’s leg got infected and he died.

“So, you see,” said the rickshaw wala, “even when we take precautions, Fate tricks us.”

With such encouragement I set off for Calcutta.

19 January 1990

A long journey across northern India. Lucknow, Pratapgarh, Benaras, Patna. People flow in and out of the aisles as if choreographed. It’s stuffy on the top tier but I sleep a lot. I’m surprised at the spareness of the big stations. It’s hard to find even a packet of Marie biscuits. The thought crosses my mind that maybe the great lurch into the 21st century that India Today so proudly heralds has been at the expense of the further impoverishment of most Indians.

I share a smoke with a masala magnate from Calcutta. He’s actually Punjabi but his family moved to Calcutta from Lahore over a century ago. He never goes back to Punjab.

“I like Calcutta because it’s the cheapest and safest place in India. You have no riots, no ghadbad.[5] The loadshedding is tolerable-nothing like in Benaras. The prices of everything is cheap—living, food, transport.”

He’s a real Calcutta booster. At one point to tells me, “Yes, the police are corrupt but at least a Bengali will do what he’s bribed to do. You give him some money and your work is done. It’s the honesty I like.”

He speaks in a soft voice. He begins to tell me about how he used to drink like a ‘mad man’. Always drunk. Always looking for a drink. He was, as he puts it, “at the last stage”. He then sought the help of a guru, whose name is drowned out by the clacking of the rails as we whoosh by a dark Bihari village. He pulls out an amulet with a hand tinted image of his guru. “Whatever he says, has to happen,” he quietly says. He places the image back under his shirt and against his chest. He begins relating more miraculous acts of his guru to a couple sitting next to him.

I climb up again to the 3rd tier and fall asleep.

20 January 1990

Calcutta is the city of superlatives. There is no end to the seeming premier-ness of the place. Most dirty city, most crowded. Most posters per pillar, most taxis per person. Most specialised bazaars. I saw one this morning which catered entirely to shoppers interested in balloons and rubber bands. Most cruel means of public transportation (hand-pulled rickshaws). Most diverse inhabitants, most rundown colonial buildings. Most cultured city: International Film Festivals, Classical music programs, Beatlemania stage show. Most touts. It’s hard to find anything new to say or any new superlative to add to Calcutta’s already superlative list of stellar ‘mosts and bests’.

I have found a room in the Paragon Hotel, one of these new tourist hostels which are the same no matter where you go nowadays. The Ringo Guest House just off Connaught Place is no different than the Paragon Hotel just off Chowringhee.

Tourists—Germans, Dutch, Japanese, Australians and a few frightened Americans—writing in small script in their journals, talking to each other about their similar discoveries and eating out at the same restaurants.

I walk up Sudder Street. I remember coming here, to the Red Shield Guest House[6],with my family every other year enroute to a deserted beach in southern Orissa/Odisha—Gopalpur-on-Sea.

I’m afraid to go Gopalpur these days. Afraid to find sparsely dressed Germans scowling at me as they strut around like they discovered the place.

In those days (late 60s) we seemed to be the only white faces in Calcutta. Sudder Street was quiet; New Market cool and refreshing; the Globe Theatre ran movies like The Bible. Now it shows Young Doctors in Love and New Market is crawling with sad Muslim touts begging you to buy or sell something. Hotels proliferate. Tourists swarm.

These tourists are backpackers. Young folks from the 1st world bumming around the 3rd. In Benaras they learn sitar, in Dharmsala they take a course in Buddhist meditation. In Jaisalmer they ride camels into the desert and here in Calcutta they volunteer for a week or so at Mother Teresa’s. They then catch a train to Puri or Gaya.

I admire (in a way) their altruism for washing and feeding the dying. I wish I could do the same. But something rubs me the wrong way. There is a feeling of inevitability to their righteousness. Mother Teresa is another stop along the way—like the journey of the cross in Jerusalem—full of good material to write home about. Mother Teresa is now another tourist franchise, another neat thing to do.

Calcutta is a pleasure to visit again despite the restless 1st Worlders who hang on like frightened knights of the tourist round table. The locals don’t seem to give a damn about your origins here.

22 January 1990

Spent a thrilling few hours wandering among colonial tombstones in the Park Street Cemetery (opened 1760). The image that comes to mind is a ghost ship shipwrecked on an isolated reef, forgotten and dark. Like all cemeteries it has an immediate calming effect. Jumbled and disorderly tombstones and mausoleums crumble in silent gloom among trees and hundreds of potted plants. Some of the paths are under repair but other outlying areas are as untouched as they were a hundred years ago.

I’m instantly aware this place is an entire city. Stately and expansive. Towering citadels with Corinthian columns, baths and porticos keep watch over a host of long-dead nabobs and Company servants far from home. Each tomb is grander than the next. Spires rise 6, 8, 10 feet above the soil in honor of a young civil surgeon downed by ‘fever’ or an indigo planter consumed by the pox. The most ordinary of India’s first British colonizers have erected over their bones and spirits structures few Presidents can boast.

The Raj was young when Park Street opened. The Battle of Plassey was only three years won. Young men with no social standing back home, here had a chance to be rajahs off the plentitude of Bengal. These young men had never dreamed of the fortunes to be made in Bengal; Bengal had no way to stop them. Park Street memorialises the sense of destiny and ostentation of the early Raj. The world was waiting to be plucked from the mohur trees. Fortunes were huge and readily won for those who showed their ruthless ambition. For them this was a larger-than-life world. I suppose a bereaved father felt it perfectly natural to raise a small Roman temple in honour of his nine-month old infant son, dead by flux. The cemetery, like the period, like the characters buried here is an overstatement. The epitaphs are sentimental and overegged. There was never a disliked, cruel or greedy person buried here.

Of course, not everyone buried here is insignificant. William Jones, the great Orientalist icon who was the first to propose the idea of a shared kinship between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, lies under a 15-foot obelisk. Charles Dickens’ second son has been lovingly moved here by students from Jadavpur University. Richmond Thackeray, father of William Makepeace Thackeray, a senior servant of the Company, lies here, as does the wife of William Hickey, India’s first prominent English journalist.

Teachers of Hindoostanee at Fort William College, traders and fair maidens, Park Street Cemetery is, more than any other place in India, a memorial to the Raj. Here one can taste the self-aggrandisement, the self-importance and most of all, the self-pity which characterises British India. You only need to close your eyes to hear them speak again. Little do they realise that their ostentatious moments of death are long forgotten and ignored.

23 January 1990

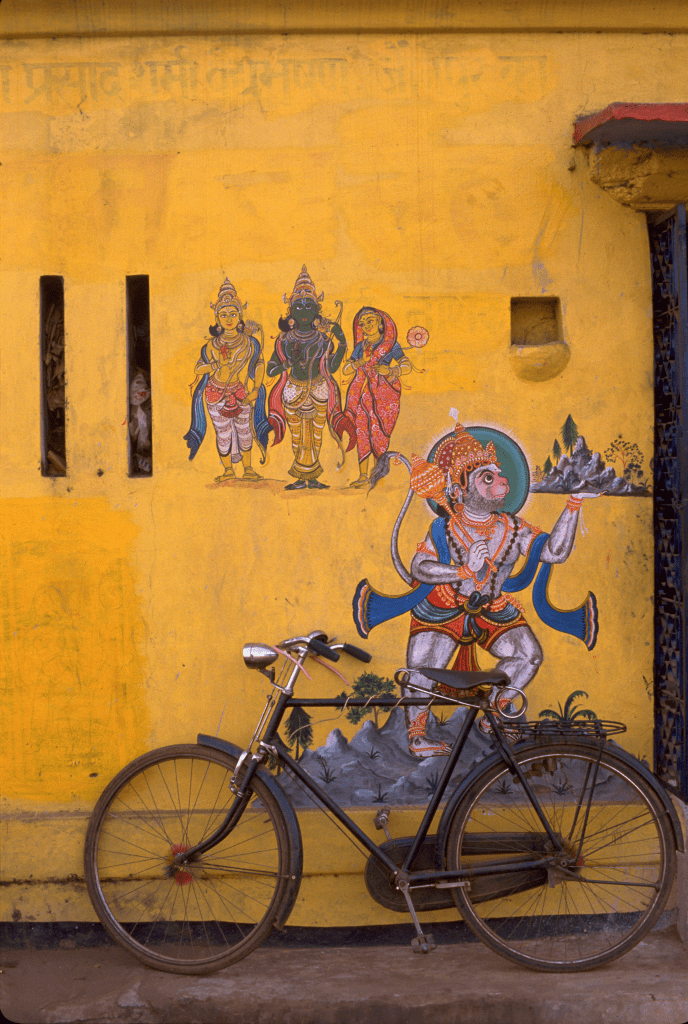

Today I arrived in a cemetery of a different sort. The great ancient temple city of Bhubaneshwar. An initial quickie around the city has left me awed with the grandeur of India—truly the Wonder That Was. I’m none too impressed however by the greedy mahantas and pundits who follow me with visitor books filled with the names of foreigners who have come before me and donated Rs. 100 or 150. They are like blood suckers who will not detach themselves from you until you fork over some cash. Muttered curses follow me when I hand over a fist of Rs. 2 notes or a tenner. “You should give at least Rs. 50,” one calls out as I walk away.

24 January 1990

Had a sleepless night. The bed in the Janpath Hotel was infested with bedbugs and the room abuzz with mosquitos. I was so tired and on the verge of the final descent into sleep only to be woken by a damn katmal gnawing at some remote part of my body. The room was distinctly shitty. A weak but persistent stench wafted across the room. No windows, only some cement grating at the top of the wall which allowed easy access for the mosquitos.

I flung my few large pieces of cloth on the floor and turned on the fan. I caught a cold and my neck ached but I must have fallen asleep between 2 and 3.

I blearily wandered off toward the Lingaraja complex which was still as impressive as it was yesterday evening. The priest left me alone to take some photos. I met two young pandas[7] who were only interested in chatting, not in extracting money from me. One was Kuna and the other Bichchi. Kuna kept classifying women into a personal scale of ‘sexual’. “Western lady very sexual”, or “Japanese lady most sexual”. He was full of obscure English aphorisms. “Every book has a cover every woman a lover”, was his favorite but others addressed less sexual subjects as well.

Bichchi was interested in telling me about politics. One of the Patnaik[8]s was in power. Another Patnaik was trying to squeeze him out now that he (the second Patnaik) had the leverage of the National Front government in Delhi. Bichchi was confident that his Patnaik (the second one) would be victorious in the end. The main complaint against the ruling Patnaik was that—as best as I could understand from Bichchi’s broken Hindi—he liked to consort with little boys. If not that he drank or smoked something that wasn’t good.

Kuna immediately spoke up. “Is there only one tiger in the jungle? They all do these things. Have you ever seen only one tiger in the jungle?”

They tried to encourage me to drink some bhang[9]. Being already light-headed from a sleepless night I declined. They extolled the virtues of bhang but cursed heroin, charas [10]and alcohol. All these vices Bichchi attributed to the Pakistanis. He saw a nefarious attempt to destroy his country. Apparently, there are in Bhubaneshwar a growing number of drug addicts.

Kuna again offered his own interpretation. “It is good. We have 90 crore[11] people here in India. If a few kill themselves with heroin good. It will keep our population down.”

I took my leave after an hour under the shade of the Lingaraja, one of 125,000 temples said to be scattered around the city. This statistic came from Bichchi. I was tired and wanted to nap but didn’t want to do it in the Janpath Hotel. Over a beer at the Kenilworth Hotel, I resolved to head immediately to Puri in search of cleaner mattresses and an airy room.

25 January 1990

Puri strikes me as an overgrown seaside fishing village. Except for the fact that it is one of Hinduism’s four major dhams[12], there didn’t seem much to commend the place. The beach is here too, of course, but it has none of the isolated charm of Gopalpur or the lushness of Kovalum. The alleys are dark and damp and only Hindus are permitted to enter the ancient Jagganath[13] temple. For a photographer it is also frustrating. The temple is set at an awkward angle which makes it almost impossible to capture well. The square in front of the temple is in glaring light most the day so people huddle in the shadows under the tarped awnings. After walking around searching for some good light, I put my cameras away. From now on I’ll stick to the alleys where little icons and shrines add color to the landscape.

I talk with Mohammad Yusuf who is selling reptile scales for the cure of piles and general unwanted blood flow. He makes rings of these and advises his customers to wear them on their left hand so as when they perform their toilet, the rings’ magical effects will “make you 100% clean. You can spend Rs. 10,000 on a doctor but these rings will cure you completely.”

He is an Oriya[14] but like most Muslims in the north speaks quite good Urdu. When I told him I was living in Pakistan he quietly asked, “What’s the news? Is it good?” I find the Muslims I’ve run into –a lot—to be sad people, though I’m probably projecting. In Calcutta all the booksellers and tape hawkers on Free School Street are Muslims from Howrah. One told me with a bit of over enthusiasm that “Hindus are the best. I have more Hindu friends than Muslims. We have no problems here!”

Another, Salim, is a waiter at the Janpath Hotel in Bhubaneshwar. He was soft spoken and left me with a feeling tender. He claimed to make Rs 200 a month in the hotel of which $150 he remits to his family. He used to work in Calcutta in a factory that makes cooking utensils but for some reason came, as he put it, “into the hotel line.” He doesn’t like the work but is stuck. He saw two postcards I had bought from a sidewalk dealer on Sudder Street. One was of the Kaaba[15] the other was of Imam Hussain on his horse. Salim kissed them and pressed them against his forehead when I offered them to him.

The Muslims seem to be accepted and other than a slight hesitation before telling me their names, they seem content. They confess to cheering for Pakistan’s cricket team but have been quite uninterested in asking me about life in Pakistan. Only one, a cloth merchant in Bhubaneshwar, asked me if I preferred India or Pakistan.

Tomorrow, I take a day trip to Konarak. It’s Republic Day and will be overrun with tourists undoubtedly.

26 January 1990

I was accompanied to Konarak by a Gujarati, Dr. Parwar. A pleasant and gentle man who had pulled himself up to a position of considerable rank and authority in a government hospital. His father was a manual labourer in Pune, “so I have seen life from close up.” Through hard work he got his MBBS and MD from one of the best medical schools in India and has since added a triad of MA’s in subjects like Public Health, Venereal Diseases and Administration. He has been attending a conference in Calcutta on Public Health Administration and has come to Puri to kill some time.

He is deeply committed to serving the people of India as a doctor back in Ahmedabad. He has no desire for an overseas job or money. He proclaims more than once how proud he is of being Indian. This is not something I hear in Pakistan very often.

Konarak is impressive. The stone sculpture is beautiful and majestic. The monument is set out as a sun chariot with 24 giant wheels pulled by 7 rearing horses. Most of the original temple has been destroyed but the remaining bits inspire awe for their size and beauty. The original temple rose more than twice as high at the remaining remnant which rises 80 feet into the air.

Dr. Parwar and I climb to the top of the temple and gaze into a deep opening. A pedestal is at one edge where we overhear a guide explain, “This is the place where the image of the Surya (the Sun God) stood”. Inside his stone head and feet, apparently, was magnet which when a certain interaction of physics and metaphysics transpired “caused the God’s head and feet to move.”

The Indian government is preserving the temple. Dozens of lungi[16] clad workers scratch the eroded stone with water-soaked bamboo brushes. Here and there new plinths and slabs of granite have been fitted into the chariot spokes and walls. Up near the top they have placed two huge Buddha-like images, upon which, during the Eastern Ganga dynasty[17] which built the temple, the sun was said to have shone continuously. One at dawn, one at noon and one at dusk. The third image is yet to be restored.

Dr Parwar and I silently take in this magnificent piece of human-divine cooperation before boarding a bus back to Puri.

[1] Raiwind, a town near Lahore, famous as the headquarters of a major Islamic missionary organisation, Tablighi Jama’at

[2] Hindustan Ambassador. Iconic Indian manufactured sedan which for decades was about the only car available in most parts of India.

[3] Literally, ‘tea water’. Colloquially used to indicate a small gift/bribe.

[4] A Sikh movement for Khalistan as a separate country was raging in the 80s and early 90s. Often trains passing through Punjab were bombed as part of the terroristic tactics of militant Sikh groups. By 1990 things had calmed down quite a bit but my question was not entirely unjustified.

[5] Hindi/Urdu word meaning ‘chaos’; ‘confusion’; ‘disorganisation’. Colloquially, ‘hassle’.

[6] Part of the Salvation Army’s global charity empire. Cheaper rates for Christian missionaries right in the heart of Calcutta!

[7] Hindi word for priest or guide to a temple. Not the Chinese animal.

[8] A prominent political dynasty in the state of Orissa/Odisha.

[9] Traditional Indian cannabis drink.

[10] Hashish

[11] Hindi/Urdu for the numerical value of 10,000,000

[12] The four dham are the major Hindu pilgrimage destinations located at each cardinal point of the compass. Dwaraka (West), Puri (East), Badrinath (North) and Rameshwaram (South)

[13] From which we get the English word, juggernaut.

[14] A native of Orissa/Odisha

[15] The stone building at the center of Islam’s most important mosque and holiest site, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia

[16] sarong

[17] 11-15th century CE

For the first several minutes he said nothing, just guiding his yellow and black Suzuki taxi through the clamorous traffic of midday Delhi. My daughter wanted me to ask him what his name was. “Jai Bhagwan,” he said. “An old-fashioned name.” His smile is half apologetic.

“You’ll be going to Jaipur? That’s a beautiful city. They call it the Pink City. Its a five hour drive from Delhi and Pushkar is another 2 or 2 and half hours further. You’ll stay in Pushkar for a few days? No? I see, just for a day. Ajmer is just half hour more away. What a place that is. Moinuddin Chisti…the Emperor of India! Will you be taking the train from Ajmer to Varanasi? No, from Agra. Ok. I see, your agent arranged it that way. Watch out for these agents. They’re in it for themselves, a lot of them.

This traffic is like this but not for too long. There’s a fly over up ahead and the road narrows so everything slows down to a crawl. But soon we’ll be moving again. Yes, that metro line was made for the Commonwealth Games in 2010. What a rip off! The organizers stole 80% of the investments. Only 20% was spent on the infrastructure. The main crook, Kapladi is in jail but what does it matter. It won’t change anything. The rich and our netas don’t give a shit. All the rules are for the poor, not one of them is for the rich. It never changes.

My people used to own the land around the airport. A long time ago the government came and forced us off the land and gave us Rs1.40 per square meter! A very low price. But they got what they wanted. You know Gandhi? They say he is the father of the nation. We say he’s the number one Thief. Don’t believe me? What did he ever do for us? Did he do anything to improve our lot? He and Nehru did everything for themselves and to make their own money and name. Gandhi, the old bastard, used to feed his goat grapes while the rest of the country starved.

The real hero of India was Subhas Chandra Bose. What a guy. You know what his slogan was? Give me your blood and I’ll give you freedom! He was a man of action. That’s why they killed him. You know Gandhi could have freed Bhagat Singh but he didn’t. He let him hang. All for his own glory.

Ambedkar? Yeah, he was a good man too. He wrote the Constitution. No one else could have done that. He was a great man actually. I have nothing bad to say about Ambedkar.

Right, we’re almost at your destination. Just 5-10 minutes more.”

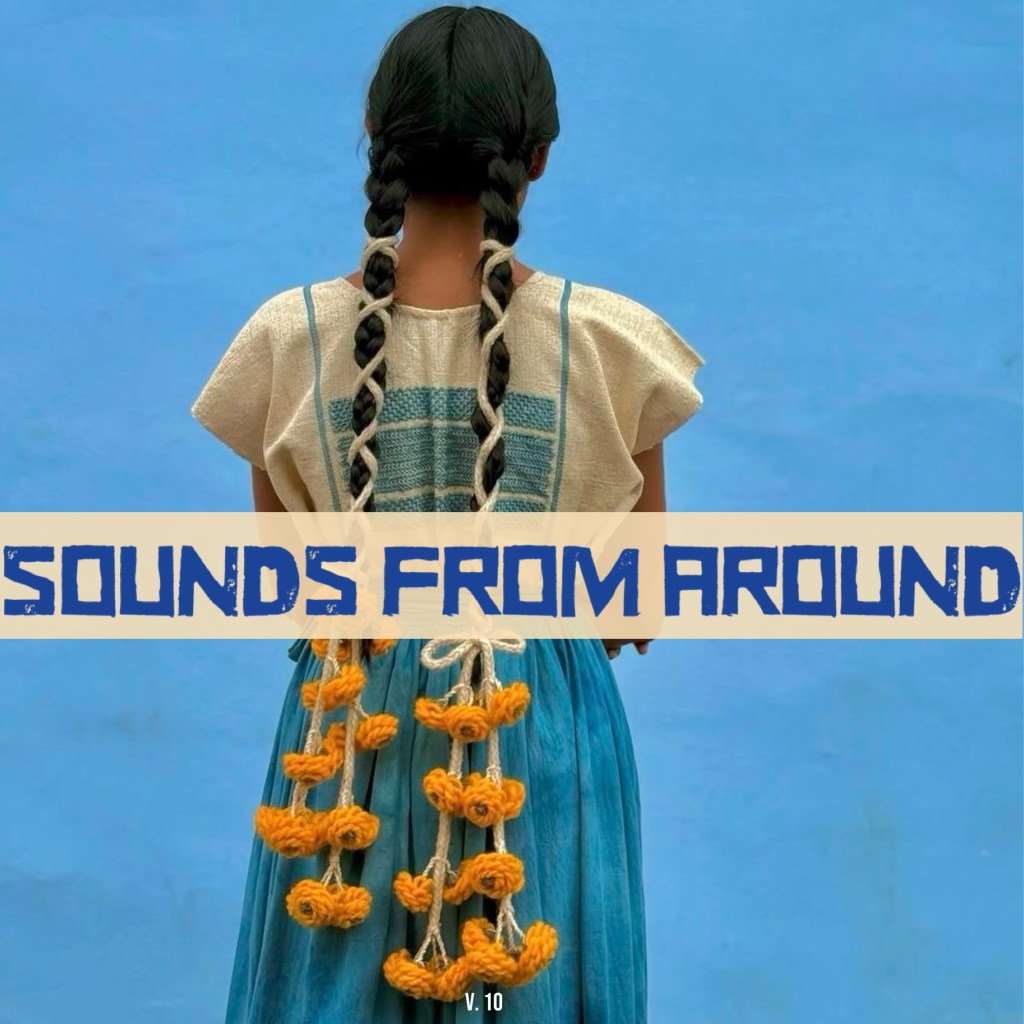

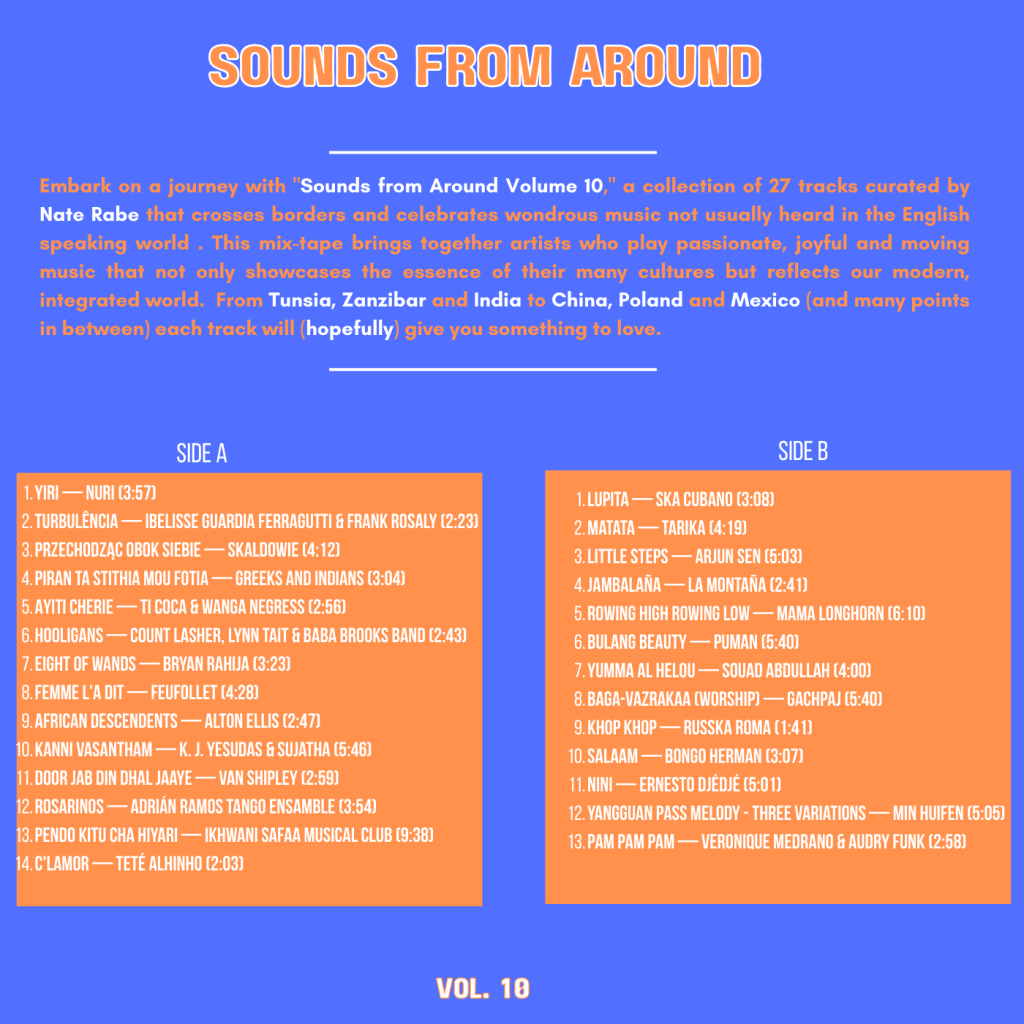

Especially consequential was the emergence of a prosaic marketing gimmick for record stores and music journalists–‘World Music’. A new category for obscure (to Western fans) African and Asian artists, singing in non-English languages.

The music these artists performed and recorded stood out sharply from the pop music of the time (especially, the American variety) with heretofore unheard instruments, revamped rhythms and lyrics in Arabic, Yoruba, Bambara, Zulu, Swahili, Lingala and colonial creoles.

The creation of this immediately contentious category/genre not only gave these artists a legitimate place within European record stores but more importantly, a platform from which they could grow their audiences, make a bit of money and in some cases become internationally feted stars.

In fact, ‘world music’ proved to be a much-needed shot in the arm for a music industry struggling with oversaturation, commercialisation and a technological transition from vinyl to cassette tapes to CDs. African bands and artists took to these new media without hesitation, especially cassette tape, relishing in their inexpensive production costs and portability. Suddenly their music was available everywhere, at home in Africa but also in Manchester, Dusseldorf, Minneapolis and Copenhagen. Fans loved it. And in no small way, ‘world music’, dominated by African sounds and artists, rejuvenated the global music business of the time.

This wasn’t the first wave of African music in Europe. The performers’ fathers and uncles, who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s just as the political ‘winds of change’ blew across Africa, had been the first to introduce African music to Europeans: Congolese rumba, soul drenched crooners from Portuguese Africa, South African jazz, Ghanian highlife. These were the sounds of the dance halls, boîtes (night clubs) and musseques (shantytowns) of Johannesburg, Kinshasa and Luanda transplanted into the pubs and community halls of London, Brussels and Lisbon.

I’m not sure what sort of fan base this first wave of African music had beyond the immigrant communities themselves. Apart from South Africans Mariam Makeba, Hugh Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim who enjoyed relatively prominent reputations internationally, few Africans broke into the American cultural mainstream. But given the nature of post-colonial European societies, especially the large number of Africans moving to Europe in the 70s and 80s, Europeans seemed to be quite receptive to this music.

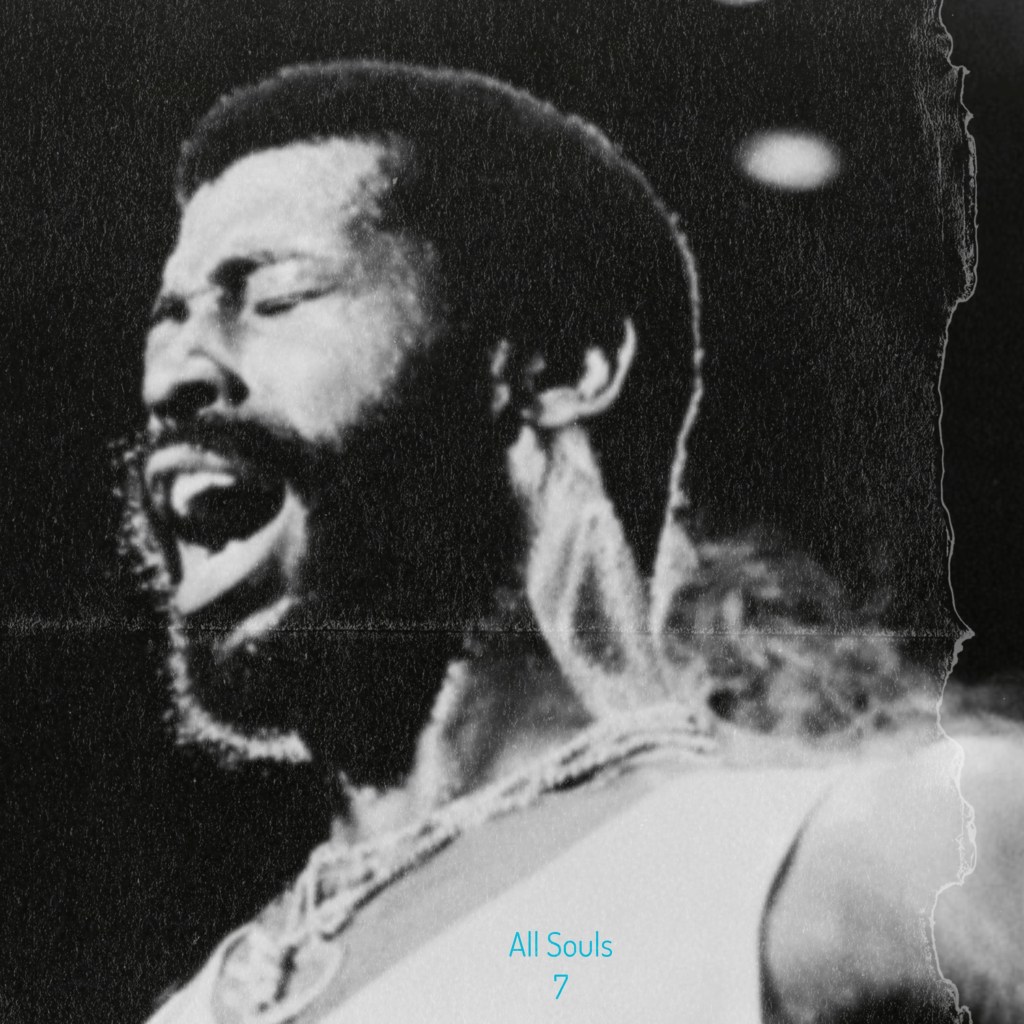

My first encounter with contemporary Afro-pop was in 1991. I was a junior staff member in the UN assistance program in northern Iraq. Living in tents against the side of a brushy hills a few klicks from the Iranian border, our evenings were monotonous. Beer, whiskey, cigarettes and music was about it. The nearest town, Sulaymaniyah, was 90 minutes away by road and in any case, offered no entertainment for European/American tastes.

Every so often we’d roast a wild boar and circle our 4x4s around the fire, open the doors, slip a cassette into the tape player and dance about until the wee hours. On one such occasion one of our Scandinavian colleagues slipped Akwaba Beach into the deck and cranked the volume.

People speak of those lightning strike moments. The Beatles at Shea Stadium. Elvis on the on Ed Sullivan Show. Dylan at Newport. A piece of music and moment in time that changes their lives forever.

The opening notes of Yé ké yé ké with its brazen blasts of brass, rapid fire vocalising and jerk-me-till-I’m-dead rhythms hit me like a bolt from on high. I had never heard anything like this. My entire body felt as if it were captured inside the music. The song sparked every dull, fuzzy and ho-hum part of my experience into a mass of shivering electricity. I hadn’t realised just how much I needed to hear this music. We played that tape over and over for months and the album has enjoyed a permanent seat on my musical security council ever since.

According to our Nordic DJ Yé ké yé ké was not some niche crate-digger’s discovery but a huge hit across Europe. Africa’s first million seller and a #1 hit on both continents. And no wonder.

Mory Kanté was born in Guinea but moved at a young age to Mali to learn the kora and further his family griot traditions. His big break came when he joined the Rail Band where he teamed up with Salif Keita and Djelimady Tounkara as part of the classic lineup of one of Africa’s iconic musical groups. When Keita left, Kanté stepped into the lead singer role before pursuing what came to be one of the most successful solo careers of any African performer.

Akwaba Beach, a dazzling example of Euro-Africaine dance/club music, opens with the #1 smash hit Yé ké yé ké and continues in the same upbeat vein for the rest of the album. Fast moving synth pop mixed with Kanté’s thrilling tenor voice, punchy kora riffs, blaring brass, feisty backup choruses led by Djanka Diabate and the percussion riding high in the mix. Dance music distilled to its essence.

Released in 1987, Akwaba Beach pounds with drum machines and shimmers with the synths that dominated the music of that decade. But unlike a lot of other relics of the 80’s, these machine instruments fit Kanté’s music to a ‘T’. It is the cocky, blatant sound required when performing in a crowded, noisy club. Unapologetic disco. If you’re looking for folk-lorish ‘authentic’ African music, you’ve come to wrong place. Kanté’s singing and playing is so good, his musicians so tuned into his vision, all that matters is the quickening of your blood.

Akwaba Beach shot Kanté into outer space as a world music superstar and opened the field for other Africans to experiment and go boldly into new territory.

__

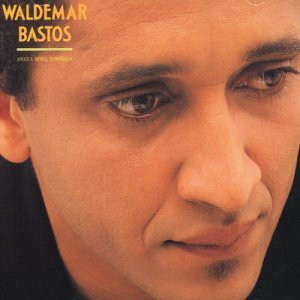

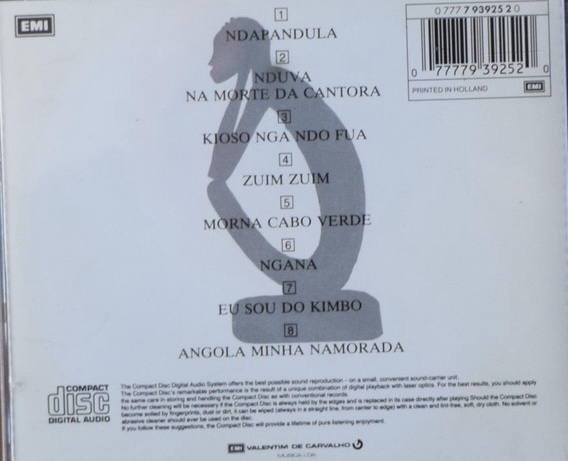

On the other end of the BPM spectrum is Waldemar Bastos’s 1990 album, Angola Minha Namorada (Angola, My Beloved). Recorded in the picturesque Portuguese coastal town of Paco D’Arcos and released in 1990, this music is urbane and sublime. There is none of the frenetic energy of Akwaba Beach within 100 miles.

Waldemar Bastos, who passed away in 2020 was born in colonial Angola in 1954. Like so many creative Angolans, he self-exiled himself from his country to settle in Portugal after it became clear that the revolution was willing to strike down musicians and other artists, not just ideological opponents. Music had played a huge part in mobilising the Angolan people to support the anti-colonial revolution, but many popular singers and musicians found themselves caught up in the 27th of May 1977 purge unleashed by the ruling Marxist-Leninist party in reaction to an internal ideological challenge. Within 18 months of securing independence, artists and musos were realizing that the dream was turning into a nightmare. Bastos left his homeland in 1982, aged 28.

Blessed with a warm and supple voice not dissimilar to that of Al Jarreau, Waldemar was considered in his lifetime a giant of Angolan music. His album, Angola Minha Namorada, was released nearly a decade before Pretaluz, the record that saw him “breakthrough” to European and American music fans in 1998.

It’s a gorgeous album. Calm, somewhat laid back in pace but deeply felt lyrically and musically. This record is the thing you want to listen to on late Sunday morning. When there is no reason to rush, nowhere to go and everything to be gained by letting Waldemar’s soulful voice slowly insinuate itself into your being. Hues of fado and tints of jazz colour this beautiful music. Though entirely different from the club music of Mory Kanté this album is another fine example of Euro-Afro pop.

XII

General Petros Zalil, known to the public as head of Party Intelligence, but to Abdul Rahman as Director General of Jihaz Haneen, was a vile Christian bug. A failed doctor and scholar, Zalil had amused his way through youth by decoding ancient dead languages and practising ‘surgical interventions’ on a variety of household pets. His family of shopkeepers, who had left Lebanon to settle in Tikrit during the Ottoman times, despaired of young Petros ever bringing honour or profit to the name Zalil, but then shopkeepers never care for politics. And no one was surprised more than his father when, after the first failed Ba’ath revolution in 1963, young Petros was charged with the task of constructing the Ba’ath Party’s secret apparatus.

Though a Christian (he liked to remind people that a cousin had once served the Patriarch of the Maronite Church as personal secretary), Petros Zalil cared nothing for God and less for man. A feverish, personal sense of injustice had fired him into the steel rod so needed by the Ba’ath Party. Zalil hated everyone and everything lukewarm, especially those weak in their commitment to the Ba’ath. He resented and eliminated communists wherever he smelled their foul stench. Timeservers in every Ministry, he smoked out like hares from their holes. Officers who had joined the ranks during the time of President Aref were cashiered, then jailed. And it was Zalil who almost single-handedly cleansed Iraq of the Jews. His bitter hateful feelings were distributed universally and democratically; there was no one Zalil did not loathe, except Saddam Hussein, the man who had personally chosen him to build the party’s secret police: the Instrument of Yearning. Jihaz Haneen. And it was because of Zalil and his secret organs that the first Ba’ath President, al Bakr, and Vice President Saddam Hussein, were able to keep the power they grabbed in July 1968.

Of course, Zalil had no military or security training — where was a poor shopkeeper’s son to find such means? — but Saddam knew that Zalil understood the most fundamental law of Ba’ath survival: loyalty. Saddam was confident that Zalil, Christian though he was, could, and would, bring order to the secret groups, which by 1963 had been completely infiltrated by the army’s generals. Perhaps because he was snatched from obscurity (Zalil was a mere sergeant in the Tikrit police when Saddam discovered him) Petros Zalil did not disappoint his master. From that day forth his mind remained vigilant to anything and anyone who threatened his Almighty, his God, his Creator, his Comrade, Brother, Father Saddam. In fact, Zalil’s personal devotion to his Saviour became the only standard by which Jihaz Haneen was to be judged. Truly, Petros Zalil was a giant of the Iraqi nation.

In the early days, General Petros Zalil — he had been promoted in 1965 — could not trust his good fortune; lest he lose the grace of his benefactor, Petros Zalil took upon himself the task of demonstrating his loyalty to Saddam at every opportunity. Even the triumph of the 1968 July Revolution did not allow him to relax. But then in December 1968 a very nasty conspiracy designed to bring down the young Ba’athist State was publicly exposed by Zalil and at last, once and for all, his place close to Saddam’s breast was secured.

The entire nation, including Abdul Rahman, had watched the disgusting interview on television or listened on the radio. Three men (one of them a Party big shot) confessed that they had been recruited by a merchant of kitchen utensils in Basra: a Jew named Nadji Zilkha. The Jew used a radio set he had manufactured and hidden inside a church to contact Israel. He had arranged for Iraqi Jews to receive military training in camps in the mountains of Iran and, with the help of the Kurds in the north, succeeded in setting up a channel through which large amounts of dollars from Israel to Iraqi Jews flowed. Such a terrible plan could only have been imagined by a Jew! Of course, Zilkha, the Persians and the Kurds were not alone. The President of Lebanon, Henry Firoun, arranged for the Director of the American Ford car company in Baghdad, also a Jew, to smuggle the Iraqi Jews into Iran by means of a Pakistani shipping company! When the men completed their pitiful confession, the judge sent them directly to prison. They never were seen by their families after that day. But the others, mostly Jews, thirteen in all, were rounded up by Zalil’s men and executed within three weeks.

On the day of the executions, Abdul Rahman and his friend Aziz went with the crowds to watch the Jew corpses swinging in Nafura Square. What a marvellous sight! Iraqis came from all across the country. Even Bedous, stinking of date oil, emerged out of the desert on their camels and pressed into the square, jumping up and down to get a glimpse of the criminals. President al Bakr shouted encouragement to the crowd, vowing to foil all the plans of the Zionists.

Like the other spectators, Abdul Rahman had no particular feelings about Jews. They had shops which everyone knew about, but they spoke like Arabs and looked like them too. As the corpses dangled in the square, the crowd was excited not by feelings against the Jews but by feelings of pride. Of victory over traitors. Until the Ba’ath, Iraqis had resigned themselves to foreign domination: Persians, Turks, the English. Everyone wanted to remove Iraqi oil at low prices. It was only when Petros Zalil took control of the secret organisations that Iraqis dared feel confident. To see the limp bodies of those traitors was a great day in Iraqi life. The people were sure that from now on all foreigners would think very carefully before attempting to undermine the State; especially, but not only, the treacherous Jews.

The response of the public and the President encouraged Zalil; more and more conspiracies were exposed. Every week the papers published the names of those who had been caught in their plottings and executed. Hundreds of Iraqis swung from lampposts in those days; and not just Jews. Christians too, and even Muslims. Zalil’s power grew with each triumph. With every exposed plan, the head of Party Intelligence’s confidence swelled. Newspapers and officials praised his efforts. His speeches, full of long, impressive words, were printed and sold as pamphlets. On the second anniversary of the Revolution Zalil gave a speech in Tahrir Square which Abdul Rahman never forgot.

‘The Iraq of today,’ Zalil shouted, ‘the great Ba’athist and Arab homeland, the womb of culture, will henceforth not tolerate traitors, spies, foreign agents or fifth columnists. Not a single one. The bastard-child Israel, Imperialist America and Persian lackeys must hear this message. We will discover their dirty tricks! We will take punitive action against their agents! We will suspend their spies from Iraqi trees, even if they despatch thousands of them! You, each of you, are the protectors of the great Iraqi nation. You must not slacken the pace we have set since the advent of our pan-Arab revolution! We have just taken the initial steps of the revolution! The great immortal squares of Iraq shall be filled up with corpses of traitors and doublecrossers! Just wait!’

The Christian general praised the success and efficiency of his secret police. But, he noted with regret, some, especially those not ‘entirely Arab and purely Iraqi’, seemed to be questioning whether it was indeed necessary any more, at this stage of the Revolution, to fill up the squares and alleys of Iraq with traitorous corpses. Some newspapers, he screamed, had begun to sow seeds of doubt within the public. The crowds attending the executions were decreasing in size. The papers were writing shorter and shorter articles on the public humiliations and executions. One rag especially, Al Anwar, was leading the way. Wasn’t the paper’s proprietor a pre-Revolutionary minister in Qasim’s thug government? A new plan was needed, Zalil bellowed, which would meet this new challenge to the victory of the Revolution.

‘Any strategem to achieve victory over the enemy,’ he continued, ‘must consider from the outset liquidating those pockets which guarantee that the enemy has information, and that play a role in generating destabilising propaganda, thereby weakening the spirits of the people and their resolve for victory. This leads to a loss of self-confidence in preparation for defeat. When we Arab Iraqis become determined to wage war against the foreign un-Arab espionage networks, we of necessity must be aware, and we must be possessed of the certitude that hitting at these networks must necessarily be accompanied by an assault on the pockets of mongrel Judeo-Persian-American exploitation. In order to purify the nation and its people, I propose to refocus our efforts on these sinister pockets of public treason.’

Three days after the speech, the owner and editor of Al Anwar daily newspaper died when his car exploded into the evening sky of Baghdad. The next day a bus carrying Jewish schoolchildren to their college was bombed as well. Throughout Baghdad, and even in other cities like Mosul and Kirkuk, prominent but suspicious journalists, professors and priests were murdered in a terrible campaign of car bombs. The explosions were so frequent that Baghdadis avoided all vehicles, preferring to walk about the city. The taxi drivers petitioned the government to take action to save their livelihoods.

Zalil’s campaign succeeded beyond his own wild imagination. Not only were dozens of State enemies eliminated but within months President al Bakr announced Zalil’s elevation to the Revolutionary Command Council. Al Bakr, they said, nearly showed tears during his speech. Iraqis had always been known for their loud mouths and boisterous ways but from the time of the rise of Petros Zalil, Iraq was transformed into a country more quiet than midnight. ‘My proudest achievement,’ Petros Zalil never tired of repeating.

Indeed, turning a nation of hotheads into a laboratory of mice within five years was a grand accomplishment. And for more then ten years Zalil was satisfied. But it was only a matter of time before the situation began to change. For ten years Zalil feared Saddam. But slowly he developed his plan to devour him.

‘Is it not often the case that the gateman is more powerful than the king?’ Zalil enjoyed speaking to his own image each morning as he shaved. As the most feared man in Iraq he had few friends but even as a boy he had preferred his own company. Other humans were an annoyance. The razor cut a path through the thick white cream, and he said out loud. ‘The king, busy within the castle, manages the affairs of his people, but he must trust the gateman to keep the enemy beyond the city walls. But should the gateman not be worthy of the king’s trust, or decide that the throne is rightfully his, since it is he who determines whether an usurper gains access to the inner court, then the king is transformed into a pawn. Who has more power? Surely, not the one who must trust in the other?’ As he splashed water onto his freshly shaved face he was satisfied that no one stood between him and President Saddam.

The gateman began to plan his own coronation.

*

In 1980 Zalil had applauded Saddam’s audacious invasion of Iran, but for years he had not been happy with the way the President was conducting the war. When Khomeini sent waves of children to face Iraqi tanks, the television and newspapers were filled with photos of fields, covered with little dead boys. Eight or nine years old. Who could comprehend the beastly nature of the Persians? Who could sacrifice their own sons in such a way?

Zalil of course cared nothing about the children. ‘Iraq,’ he shouted into the mirror one morning, ‘has been brought to its knees by toddlers.’ The refusal of Iraq’s top officers to slaughter the children was a point of humiliation, a sign of weakness that Zalil could not admit. ‘What better chance will God give to Iraq than this?’ he demanded. He ran water over the razor to relieve it of his heavy whiskers. ‘Never again will the road to Tehran be covered with such a plush carpet. Our tanks should roll over these Persian children as if they were a field of onions.’

It was not just the army’s reluctance to kill children; there was Saddam’s frequent change of field commanders which tried Zalil’s patience beyond all limits. For more than ten years Zalil had developed Haneen networks in every barracks and every regiment and battalion in the army and airforce. Many of the top brass were either fully Haneen or had sympathies with the head of Party Intelligence. Of course, these men were loyal Ba’athists; their allegiance to the Ba’ath Revolution was unquestionable. But they had been groomed by Zalil. It was he who had rigged their promotions and plotted their careers with the mind of a chess player; their ultimate loyalty was to him, not the President. ‘See again, how the gateman is more powerful than the king.’ He winked at himself in the mirror.

One year the Iraqi army lost over twenty top field commanders. And middle rank officers? Beyond counting. Every time a battle was lost and even once when the broken axle of a supply truck caused a delay in the refuelling of an advance unit the commander in charge was summoned back to HQ. Bang. Dead. Soon the High Command didn’t bother to make the arrangements to bring the officers back to Baghdad; they were shot in their own units, usually by their own soldiers.

‘This is intolerable. How can the President demand vigilance if he is intent on plucking out every eye I have put into place?’ He made another large sweep through the remaining foam of his pudgy face. ‘Damn!’ A small trickle of maroon blood moved down his right cheek. Zalil grabbed a towel with exasperation. ‘This man’s erratic behaviour threatens my entire life work. I cannot permit this to happen.’

*

The message was dispatched in a sealed envelope from the Ministry of Antiquities to each of their homes by the official ministry courier. In the envelope was an invitation to a celebration organised on the occasion of President Saddam’s birthday on April 28. Each of the recipients — thousands of officials around the country — was invited to make a donation of no less than one hundred dinars, and to select an ancient Sumerian symbol provided in a list by the Ministry of Antiquities. The donation would be used to mint a coin embossed with the name of each official and the special ancient Sumerian hieroglyph and was to be presented to the President on his birthday as a sign of the gratitude of his ministers.

The thousands of envelopes contained identical letters, worded exactly the same, and included the same set of Sumerian hieroglyphs. But in the envelopes delivered to the Ministers of Oil and Transport and Industry, Generals Fikri and Mahmood, and Dr Idris, Chairman of the Regional Command Council of Baghdad, Petros Zalil included his own short list of Sumerian symbols. Each man, a conspirator with the head of Party Intelligence, had been instructed to select one symbol only from Zalil’s list and return it with their invitation, and in this way indicate their participation in the gateman’s move against the king. Within a week Zalil had received five of the six special invitations properly marked. The Minister of Transport had lost his nerve and decided not to return his invitation. Without a second thought the viperous Zalil struck: two days later the Minister was discovered by the departmental cleaner, dead on his office floor, a bottle of turpentine next to his head. Five litres of fluid were pumped from his stomach when his bloated body was delivered to the Emergency Ward at Medinatul Tib hospital.

Each of the plotters had been in contact with their spider, Zalil, for some time, and each had his own private complaint. The Minister of Oil had been brought to financial ruin by the blackmail of Saddam’s half-brother, Barazan. Dr Idris’s son had been denied treatment for his cancer in Germany and died at the age of seventeen. The Generals, of course, feared for their lives as long as the Persian war raged on year after year. The Minister of Industry, Haider al Haji Younus, Abdul Rahman’s relative, had been three times denied a seat on the Regional Command Council of Tamim Region.

After the untimely, but little mourned, death of the Minister of Transport, Zalil arranged a large dinner party at his residence to mark a grand Revolutionary occasion. Among his guests were not just his colleagues in the conspiracy, but members of the President’s family, members of the RCC and the Prime Minister, Mr Izzat Qureishi. Zalil had prepared, and delivered very dramatically, a grand speech to mark the occasion and, of course, crates of whiskey, arrack and vodka and the most sumptuous meal had been laid on for the guests. But by the early hours of the morning Zalil was left alone with just his five co-conspirators. In a private study, in which every listening microphone and every hidden eye had been disabled prior to the start of the evening’s festivities, Zalil called the final meeting of the plotters to order. Each of the men present had been given their assignments: the Generals confirmed the availability of two thousand men and many armoured personnel carriers; the Oil Minister had already begun to scale down production, and the pipeline to Turkey was ‘closed for repairs’. Haider, Minister of Industry, had been in contact with Iraqi exiles in Europe for the past two years. Some had already returned; others were on the way. The only thing remaining was to finalise the actual plan. Zalil confirmed that Saddam would be out of the country for two weeks in June, on official visits to the Soviet Union, East Germany and Finland. Upon his return to the country, the group would assassinate the President.

Assassinating Saddam was a game of Russian roulette. The President of Iraq never travelled in his official, announced motorcade. Always, five dummy convoys were sent through the streets of Baghdad, each taking different routes to the destination, and even Saddam himself knew which motorcade he would choose only at the very moment he stepped into a vehicle.

But it was Zalil’s belief that as gateman he could successfully foil the system. The system, after all, had been designed by him. Within Haneen a unit answering to Colonel Nizar, was responsible for monitoring each and every alley and street in the city. Every lamppost, every window, every turn and every manhole was known to them. Colonel Nizar’s information was priceless, and he was with the plotters. Determining the routes of each convoy would not be difficult: Nizar’s unit was responsible for selecting and preparing and securing all routes on every Presidential journey. Only the driver of the lead vehicle, a Haneen employee, knew the route of the convoy, and that only a few moments before the beginning of the journey when he received the instructions, in code, on a secure radio channel.

Zalil and Nizar had arranged that along each route, near a predetermined crossroad, the first vehicle of each convoy, pre-planted with a bomb, would explode. Discovering which vehicle would lead each convoy was also simple. Always a dark-green, almost black, Mercedes provided by Party Intelligence and driven by Haneen drivers. This system had been instituted by Zalil in 1970 and it had never changed. A wire laid across the road would send an electronic signal causing the bomb to explode just as the first vehicle rolled through each prearranged junction. This is where the Generals became useful. Ten armoured vehicles and two hundred men fully equipped with rocket launchers, machine guns and grenades, hiding in pre-arranged vacant rooms and buildings in the side streets, would burst forth, firing openly on the remnant of each convoy. Zalil’s intention was to decimate all five convoys. The explosion was only diversionary. The President’s vehicle is always fourth in the convoy. As the first two or three cars were caught in the mêlée, the driver of the President’s car, trained for such exigencies, would turn instinctively into the nearest street. Because Zalil and Nizar had selected especially narrow cross streets for each explosion, the driver of vehicle number four in each convoy would have no option other than to turn unthinkingly into the plotters’ side streets. There was no way Saddam would be able to escape.

The plan was faultless. While the convoys were under attack Zalil planned to announce a popular uprising, which the returned exiles were responsible for generating in towns all around the country. ‘By noon, Ba’ath power will be wiped from the pages of Iraqi history,’ he cooed at his tired but eager guests. The sun was rising over the Tigris. Zalil’s dinner party was over.

*

It is true, Zalil’s plan was daring and bold and he had more support than any other plotter before him. To have even the overseas Iraqis supporting the show was Haider Younus’s great contribution. Zalil could not fail. Everything was under control. But then something unexpected and miserable happened. In May, the Prime Minister, Mr Izzat Qureshi, ‘resigned’ and the plotting Minister of Industry, Haider al Haji Younus, was appointed in his place.

As much as anyone, Haider was taken by surprise by this sudden twist of fortune. For years he had struggled for promotion to the Regional Command Council and each of his attempts had been rebuffed. He had resigned himself to dying as Industry Minister, until resentment led him to Zalil’s group. But now, so unexpectedly, Haider was Prime Minister! A seat on the Regional Command Council, dreams of which, until then, had tortured his every waking moment, now, from his lofty new perch, seemed ridiculous. And the resentment he had harboured towards the President for so many years turned, overnight, to bottomless gratitude.

Of course, Haider had been selected as Prime Minister because he was a weak and completely dependent character. Unlike Prime Minister Qureshi who preceded him, he did not enjoy the backing of foreign interests. He was extremely dispensable. The country was in the midst of unexplained bombings and unrest was increasing, not just in Baghdad but throughout the country. If Haider Younus was unable to do what was needed, no one would shout or cry when his time came to be sacrificed.

Naturally, Haider was in a state of confusion as he took his oath of office. He swore allegiance to the Party, the State and the President himself, but at the same time he had made promises to the gateman to destroy all three. It was time to make a quick calculation of risk, but nothing is ever valuable if done quickly. On one side, he knew that Zalil was still depending on him for his support. In fact, on the day of his promotion, Zalil sent a message and a bottle of twenty-one year old Chivas Regal to Haider, congratulating him on his good fortune and predicting an even brighter future — a signal that the plan was to go ahead on schedule. On the other side of the balance, there was the President. Haider was overcome with gratitude by his elevation. Horses, it is said, sometimes bite their master’s hand, but Haider did not consider himself to be a horse. Not unnaturally, his views on the plot changed dramatically.

But not only was Haider not a horse, he was not a decisive creature either. For three weeks he did nothing to suggest to Zalil and his conspiring colleagues that he was in two minds about the plot. And just like Zalil, and all the others who had been drawn close to the Presidential breast had done before him, Haider wanted to demonstrate his loyalty to Saddam. So on the day the President was to return to Iraq to meet his almost certain death at the hands of Zalil, Haider requested the President’s son, Uday, to pay a visit to the Prime Minister’s office.

‘I must notify you,’ Haider told Uday, ‘as the President is out of the country, that a plot to assassinate your father has been uncovered. The plotters are at this very hour gathering at the airport.’ He then elaborated the plan in detail.

*

At Saddam International Airport, Zalil, with most of the government’s senior officials and military top brass, had arrived to welcome the President. At 9.45 a.m. he noted that Haider had not yet arrived; the President’s plane was due to land at 10.10 a.m. Without hesitating, he approached the Minister of the Interior and the Minister of Defence.

‘I fear there may be trouble today. The Prime Minister, that rodent Haider Younus, is not here. Indications are that he is involved with Generals Mahmood and Fikri and Colonel Nizar as well as that old fart, Basil, the Oil Minister. I have just received information that their objective is to assassinate not only the President but most of us here.’ He paused. A vehicle pulled up behind the men. ‘Do I need to insist that we should depart immediately and return to the city and do our best to protect the President?’

The three men ducked into Zalil’s vehicle. Inside, Zalil and his two bodyguards removed their pistols and pressed them against the sweating necks of the Ministers. Zalil commanded his driver to head north to Baq’ubah. Before Uday and Haider had been able to notify Military Intelligence, Zalil had disappeared from Baghdad with his two hostages like a cloud in a drought.

When the President’s plane landed, Saddam was advised to remain on board while the plotters, Generals Fikri and Mahmood, Colonel Nizar and the Oil Minister, Basil Hamdoon, were arrested. The army units waiting quietly in their hideouts on the side streets panicked when the time for their action long passed. By evening more than three hundred arrests had been made.

The following day, after the body of the Interior Minister was recovered from an alley in Kirkuk with nails throughout his body, Saddam placed a price on the gateman’s head. Three days later, the Minister of Defence was discovered by a taxi driver, lying in the middle of the highway at Chamchamal. His throat was slit and not a stitch of clothing was on his flabby body. Zalil, the rumours went, escaped to Iran where the Persians welcomed him like an Olympic champion.

Abdul Rahman had been aware of these incidents. Who hadn’t? Each new development was presented in the papers as another demonstration of the invincibility of the President. And so it seemed. If Zalil, that most intimate confidant, could not succeed in his evil, surely the Spirit of the Arabs rested on Saddam. Abdul Rahman trimmed the newspapers like a rose bush, grafting the small news items into his accounts ledger. The involvement of his relative in the mess had disappointed him but, as Haider had acted properly by exposing the plot, Abdul Rahman rested in the confidence that it was the President who was now indebted to his relative. Abdul Rahman’s own destiny was secure. Of this he was certain.

But Saddam was not fooled. For Haider to know about Zalil’s plot in such detail he must have been in on the conspiracy. Prime Ministers, despite their lofty office, do not enjoy direct access to the secret goings-on of Jihaz Haneen. Saddam had chosen Haider because he was expendable and so he was expended. After a meagre six weeks in office, Haider was arrested by the Emergency Law and Order Administrator and taken to Abu Gharaib prison. Within eight hours he was no more.

*

That damp July morning, after the arrest of his relative, as Abdul Rahman drove through the city to his small flat, scales fell from his eyes. His household was in an uproar. He strode into the dining room with motivation and strength, persuaded that whatever confusion he himself felt he would not show it to his family. At the dining table his wife sat sobbing. Jamila, the servant girl, tried to comfort the woman, but was pushed away each time she reached toward Abida’s face. Haroun and Hassan jumped up as soon as they saw Abdul Rahman and said in unison, ‘Father… ’ They wanted to say more but reconsidered. Abdul Rahman sat down next to his weeping wife and told Jamila to bring a cup of coffee. His sons remained standing as if frozen in ice.

‘What is the matter, Abida?’ he asked. ‘Why all the commotion?’

Abida continued to sob for several seconds before lifting her face. She tried to speak but only managed to blub more tears.

‘What is it? Has someone broken into the house? Come now. Be calm. What happened?’ Abdul Rahman’s composure was strained; his mind already confused by the night’s momentous changes. He reached towards his wife and placed a hand on her shoulder. He squeezed her firmly. His mind remained filled with the weirdness he had seen on the streets; he was exhausted. A strong urge to consult his ledger for reassurance that the Prime Minister was, in fact, still on his seat, washed over him. He wanted nothing more than to look at the man’s photos and to re-read the articles of his appointment.

He was growing more impatient with his wife every passing second.

‘Abida!’ he said sternly. ‘Stop nittering and tell me what is the problem! I have a headache like a mountain.’

She wiped her wet face deliberately. Her lips quivered. ‘Zubeida has disappeared. She hasn’t returned since last night. With the changes today I’m afraid she… ’ Abida could say no more.

His hand fell from her shoulder. In the kitchen Jamila, the servant girl, had stopped making coffee, and waited. The house was quiet except for Abida’s soft, unceasing sobs. Haroun and Hassan stood still, daring only to blink. Abdul Rahman leaned back in his chair and closed his eyes.

‘Why did you allow her to leave the house? And where did she go? Why didn’t you send a message to inform me last night?’ His voice shook with fear.

‘She went to the tutor’s house yesterday afternoon, I think.’ Abida said, still looking at her lap. ‘You are the one who is always pushing her to keep studying even though the world is crumbling around us.’

‘But why didn’t you inform me yesterday?’

‘How am I to contact you? There is a curfew in the city from six p.m. Of course, that is something you haven’t noticed is it? But I’ve noticed it. So has the rest of the city. If we go outside this house after that hour we can be killed. How am I to inform you? I have no number to call you at your office.’

‘Of course, there must be an explanation. If there was a curfew she must have stayed at Mr Mohsin’s overnight. I’m sure Zubi will return as soon as the buses begin to move.’ He felt relieved as he spoke the words.

‘I have called Mr Mohsin. He had no plans to see Zubi yesterday. Only on Thursdays and Mondays since about the last two weeks.’

‘Don’t speak rubbish, bitch!’ he shouted. The chair fell over as he pushed away from the table. The two boys scampered from the room like startled rabbits.

‘In one night my relative, Prime Minister Haider, has been deposed and jailed. The country I thought I lived in and served has changed before my very eyes. I see devils parading up and down the streets. The radio is chanting strange names and barking strange orders. And now…this.’ He moved closer to his wife and pulled her from her chair. She averted her puffy face, flushed from a night of tears. She shivered in his hands. Abdul Rahman had never beaten his wife or children, but that day he raged within himself. He wanted to lash out and hit her for suggesting that his little canary had disappeared. As he loosened one hand he remembered Jamila, the servant girl in the kitchen. ‘Get out! You should never have been in this house. Go! Run! Now!’ he shouted. The front door shut quietly as she slipped away.

Abdul Rahman turned his attention toward his wife. He let her drop to the floor and kicked her; she rolled over and hit her head against the dining table. ‘Where is my daughter? What are you hiding from me? Where is Zubi? Zubi, where are you?’ he called out. His voice bounded off the walls and back into his face as if it were slapping him. Absolute desolation crept into his heart. ‘Where is she? Where is my angel?’

Abida pulled herself up against the wall. She shook her head in silence.

Unable to control his grief he lunged and fell to the floor next to her. His fist hovered for a moment above her face but instead slammed into the wall. And then again, and again. He shouted and pounded until his knuckles split and blood stained the sleeve of his shirt.

That day he didn’t sleep. His mind was a slab of grey slate. Heavy bags were tied to his feet and dragged behind him everywhere he went. Although he drank lemon water constantly, each time he opened his mouth his tongue felt as dry and unwieldy as an old shoe. His heart danced in his chest like a drop of water on a hot plate. He asked Abida to call a doctor, but which doctor was willing to leave his house and come to Abdul Rahman’s? Throughout the day he tended a grief so deep his limbs and ears stung.

Abida refused to join him in his room, and sat without moving in front of the TV, staring at the announcer who read ever longer and more detailed proclamations from the Emergency Law and Order Administrator. ‘In order to ensure maximum peace and stability in the coming week…’ Abida paid no mind. The images coming from the screen passed before her as if they were paying last respects to an acquaintance. Her head was cut slightly where she had rolled into the table; there was no blood but she sucked on her bitter thoughts. ‘I no longer care about your daughter,’ she said in the evening. ‘Zubeida has always been yours, not mine. Your grief leaves no room for me to partake.’

*

Thirty-three days later the Emergency Law and Order Administrator himself was deposed. The new Emergency Law and Order Administrator, Colonel Abdallah, proclaimed that Iraq was now under temporary martial law. In his first address to the people he condemned by name the man he had just overthrown, calling him a jackal. Abdallah emphasised his sincere desire to set the country back on its historic and stable path of development. He said, promised, stressed and underlined many other things but one in particular shocked Abdul Rahman beyond belief.

‘The motivation of President Saddam Hussein and the RCC in embarking on this unprecedented act of armed intervention is to ensure the secure and stable and prosperous future of our country and its citizens. In the recent past some leaders of the State have been isolated from the people. The aspirations and ideals of the common man, the demand for justice and honesty, have been ignored. Even more, they have been deliberately trampled upon. A vast network of repression has been operating in this country with the primary purpose of crushing the spirit and voice and will of the people. It is a sad and bitter reality that in our country there have been many abuses of human rights. The police and special branches have arrested thousands without reason. Hundreds of these have disappeared or been returned to their families after having endured horrific torture and bodily abuse. Some intelligence organisations have been the leaders of this atrocity against the country’s dignity and honour. While there is a legitimate need for the State to defend itself against internal enemies the activities and intentions of some intelligence networks can only be termed criminal. Is it any wonder that you the people of Iraq have demanded the overthrow of this band of murderers? It is only because the President of the Republic knows that you endorse this intervention that I am able to proceed.

‘With immediate effect and until notified by the Emergency Law and Order Administrator, the activities of all intelligence, counter-intelligence, investigative and interrogative bureaux and departments are disbanded and dissolved. All personnel employed by these departments and bureaux are ordered to remain at their place of residence until further notice. They are forbidden to travel beyond the borders of the country until such time as the ELOA determines their appropriate recompense.’

Yesterday was the biggest day on Melbourne’s sports calendar, the Australian Football League’s Grand Final. This year the pre-game entertainment featured none other than Snoop Dogg. A controversial choice to be sure. But then so was Meatloaf back in 2011. Ranked as one of the stupidest moves by the money fiends that control Australia’s beloved, unique form of football, Meatloaf’s appearance was hated by fans (Meatloaf’s included) and forced the Has-Been to publicly apologize for his poor outing.

It’s the Australian way it seems when it comes to welcoming international superstars. There was Judy Garland in 1964 (deprived of her pills by Australian Customs) who refused to leave her hotel for three days. And Joe Cocker busted a few years later.

In 2015, Johnny Depp and his girlfriend, Amber Head, were forced to grovel in front on our media and courts to express their regret for failing to declare two pet dogs that accompanied them, thereby avoiding the usual 10-day quarantine. At one point the fiery (and often inebriated) Minister of Agriculture, threatened the dogs with pet-euthanasia, if the Hollywood power couple refused to pay public penance. In the words of Depp, “when you disrespect Australian law, they will tell you!”

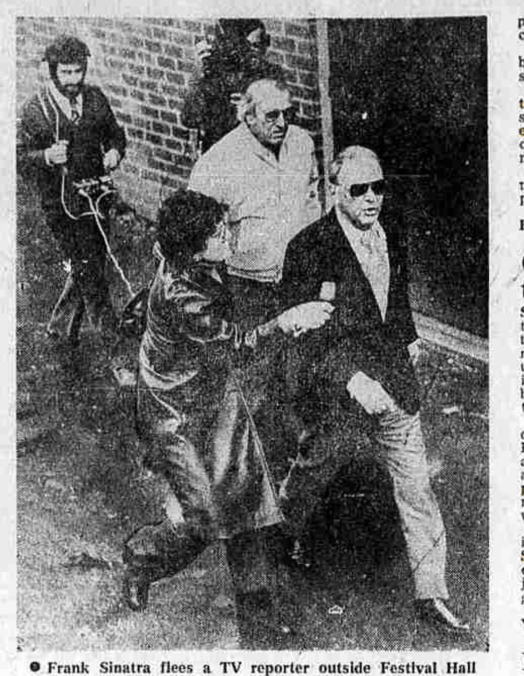

Frank Sinatra would have 100% concurred with that statement. Perhaps of all the superstars we’ve harassed, it is somehow appropriate that The Chairman of the Board’s experience sits at the very top of the list.

Frank first toured Australia to in 1955. But from the moment he and 14 year-old Nancy stepped off the plane at Melbourne’s Essendon airport, he was met with derision. Fans who had gathered at the airport hoping to share a bit of banter with their hero, quickly turned hostile when he managed but a single wave and half a smile before stepping into a limo and being whisked away to his hotel. From Cheers to Jeers went the headlines.

The shows themselves went off a treat. Fans raved how he sounded just like his records. Motorists passing by the West Melbourne Stadium double parked as his voice carried out into the street. A triumph all round. Frank loved Melbourne, the fans loved Frank. The (lack of) incident at the airport the day before was forgotten. After all, it had been announced that Sinatra would appear at his hotel for breakfast; fans would surely be able to get a second chance to hear him speak to them.

Alas, the headlines the following day read: Frank Sinatra Fans Miss Out Again. The hotel’s manager was given the task to confront the angry fans and chock it up to a ‘misunderstanding’.

Two years later, a second tour Down Under was scheduled but Ol Blue Eyes abruptly turned around in Honolulu. Apparently, Frank’s decision was based on the fact that sleeping arrangements for his musical director had been overlooked for the onward journey to Australia.

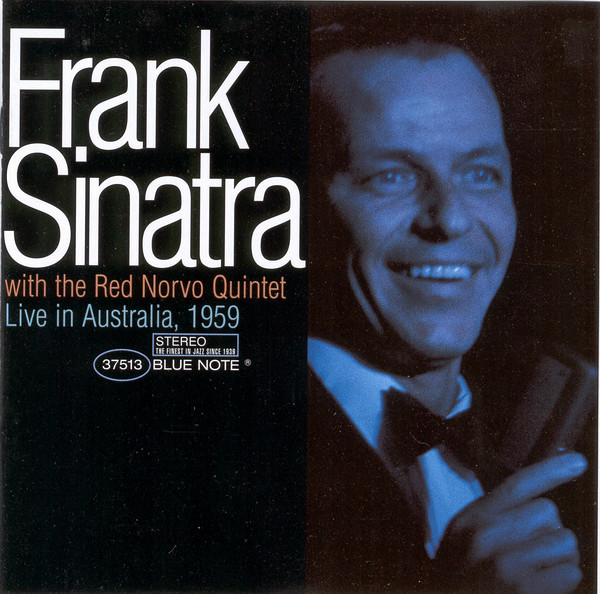

Seven shows were cancelled leaving his promoter the ugly job of refunding 23,000 tickets to ever-more cheesed off Australian fans. In January 1959, Frank tours again. He’s still stand-offish in public but in outstanding form in his shows which are supported by the Red Norvo Quintet. His private life is dominated by his unsuccessful attempts to regain the love of Ava Gardner, who just so happened to be in Melbourne as well, filming (with Fred Astaire and Gregory Peck) On the Beach. When a reporter in Melbourne dares to ask him a question, Sinatra grunts, “Misquote me kid, and you’re dead with me. In fact, I’ll sock you on the jaw.”

On the 1961 tour he ignored Melbourne altogether, doing four shows in Sydney and then flying back to familiar Californian shores.

Things got completely crazy in 1974. After being tsunamied by rock ‘n roll for most of the previous decade, Frank was finding a fresh relevance. He was out and about. Touring the world. Australian fans once again forked out their new Aussie dollars to spend an evening with their Man.

On 7 July, Frank flew into Sydney as grumpy and aloof as usual. Plane to Rolls Royce to Hotel. Nary a smile or wave to his adoring fans and a press corps salivating at the prospect of a scandalous headline or so.

On 9 July, Frank’s arrival in Melbourne was memorable in the main for his refusal to acknowledge the press and shoving a fan out of the way. So harassed did he feel that he ran from his private jet to the awaiting limo. So far, typical Frank behaviour.

At that evening’s show at Festival Hall, Frank’s first appearance in the city in fifteen years, he delivers what is now considered one of his best live performances. He’s relaxed, his voice is as good, if not better than it’s ever been.

So relaxed was he that in his first monologue Frank sums up his views on the local press. Horrified and shocked, a couple of local unions (The Professional Musicians Union and the Australian Theatrical and Amusement Employees Association) announce that his second show, scheduled for the following evening, would be cancelled unless Ol’ Blue Eyes issues an apology. This demand is met with scorn by Sinatra and his entourage. The press, he said, owed him an apology for 15 years of treating him like “shit”.

Now other unions pile on. Frank is not permitted to leave his Boulevarde Hotel room. He places a call to his pal, Hank, aka Henry Kissinger, asking him to intervene. Word on the street has it that Jimmy Hoffa has also been contacted to threaten his Aussie counterparts. An international incident is brewing.

The foam in the mouths of the press can no longer be hid. After the first show in Melbourne, his bodyguards, beefy mafia types, assault a news cameraman nearly chocking the man to death. The unions respond with a ‘black ban’. He is to benefit from no public services whatsoever. No security. No police escorts. No room service. No fuel for his plane. No passport checks. Nothing. Frank Sinatra is a prisoner.

The overlord of all of Australia’s powerful trade unions, a certain Bob Hawke, is persuaded to step in. In the initial meeting neither party budges. Frank sends word to Hawke, “I’ve never apologized to any one and I’m not about to start now.” As the unions huddle Sinatra’s entourage sneak him out of the hotel and race to the airport where the media reports, he will meet with Hawke. But his private jet defies air traffic control and takes off to Sydney, leaving an embarrassed and royally pissed off Hawke looking like a chump.

Unfazed but seething, Hawke flies up to Sydney. In response to Sinatra’s lawyer’s demand for his plane to be refueled, Hawke delivers a classic Aussie ultimatum. This brings the Chairman of the Board out to meet Hawke for the first time. Hawke issues his ultimatum again to the Man himself. After several minutes of ‘nattering’ Sinatra returns and asks Hawke for suggestions of what to put in the apology. Within an hour or so they agree on the words, and Frank’s lawyer descends to the press and reads the statement. Frank Sinatra apparently “did not intend any general reflection upon the moral character of working members of the Australian media” and regretted both “any physical injury resulting from attempts to ensure his safety” and the inconvenience to patrons.

A few days later at Carnegie Hall, Frank told his audience, “A funny thing happened in Australia. I made a mistake and got off the plane.” He then went on to target Rona Barret, a prominent female journalist of the day, by saying, “What can you say about her that hasn’t already been said about… leprosy?”

As it happens, Snoop Dogg’s show was the bomb. Most punters on social media are saying it’s the best show the AFL has ever put on. As for Frank, well, he did return to Australia 14 years later, in 1988. Bob Hawke was now Prime Minister. Upon arrival Frank meets with the press and even poses with the ‘bums and parasites’. He may have been an asshole but he was no dummy.

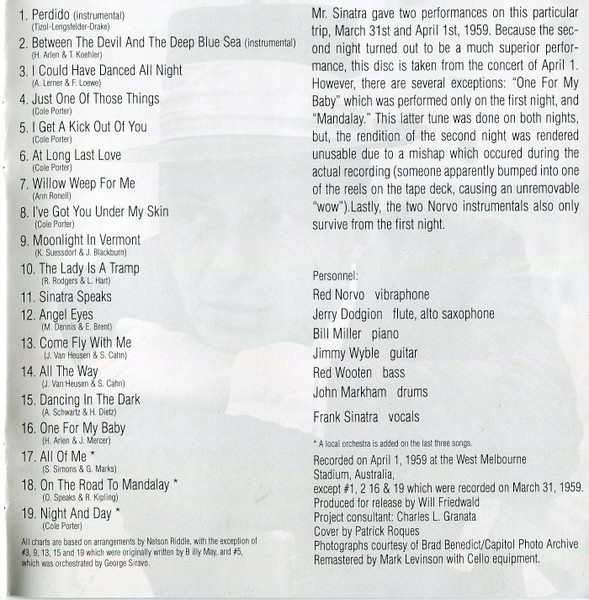

Here is the famous first Melbourne show in March 1959.

Long the favorite of collectors, who have cherished their bootlegged copies of the concert for years, Frank Sinatra with the Red Norvo Quintet — Live in Australia 1959 was finally released officially in 1997, nearly 40 years after the concert was given. In many ways, the wait was actually positive, because Sinatra’s loose, swinging performance is a startling revelation after years of being submerged in the Rat Pack mythology. Even on his swing records from the late ’50s, he never cut loose quite as freely as he does here. Norvo’s quintet swings gracefully and Sinatra uses it as a cue to deliver one of the wildest performances he has ever recorded — he frequently took liberties with lyrics while on stage, but never has he twisted melodies and phrasings into something this new and vibrant. The set list remains familiar, but the versions are fresh and surprising — “Night and Day,” where the song is unrecognizable until a couple of minutes into the song, is only the most extreme example. And the disc isn’t just for the hardcore fan, even with its bootleg origins and poor sound quality — it’s an album that proves what a brave, versatile, skilled singer Sinatra was. It’s an astonishing performance. [All Music Guide]

Abdul Rahman locked the drawers of his steel desk and put on his leather jacket. An unusually cold rain had been falling all night, spreading chilliness and mud throughout Baghdad. Clouds obscured the normally intense summer sun. Leaving his office he walked outside where Aziz, his oldest friend, was leaning against his motorcycle listening intently to the first news bulletin of the day. He motioned Abdul Rahman to be quiet and to join him on the motorcycle.

‘The state of emergency will remain in effect until further notice. All citizens are notified that the curfew currently in place will be extended from four p.m. to six a.m. and will be enforced with shoot-to-kill orders. Only personnel involved in official capacities and selected medical personnel will be allowed to move during these hours. The Emergency Law and Order Administrator, answering directly to the RCC, is charged with the enforcement of the curfew and all further proclamations. As of midnight all Governorate and city governments are dismissed and are replaced with ad hoc Security Committees. The office of Prime Minister will remain vacant until further notice.’

Aziz fidgeted with the small radio, moving the antenna about as if trying to make contact with flies. Abdul Rahman stopped his arm. His voice was filled with panic. ‘A new Prime Minister? What has happened to Haider Younus? Who is this new Administrator? What has happened?’

Aziz raised a finger to his lips and made a shushing sound.

‘All universities, colleges and other institutions of education will remain closed until further notice. The Emergency Law and Order Administrator appeals to all students and teachers to desist from non-educational activities or risk severe repercussions. All citizens are forbidden to leave the country. All citizens providing aid and assistance to the following renegade groups are ordered to cease such assistance, otherwise be liable for severe repercussions: the National Relief Committee, the Flag of Justice, the Party of God, the National Democratic Party, the People’s League, the Committee for the Cessation of Human Rights Abuses, the traitor Petros Zalil…’

The bulletin continued buzzing like an irritating mosquito.

Abdul Rahman could no longer sit quietly listening to the radio announce the destruction of the world. ‘Aziz, tell me, what is all this? Is this some joke? What is all this nonsense about Law and Order Administration? What happened to Haider Younus, the Prime Minister?’

‘He’s been arrested.’

‘Who has been arrested? You mean Haider Younus? The Prime Minister has been arrested? But he’s my relative…this is impossible. Who has arrested him? How can they arrest the Prime Minister? They can sack him, or he can die, or resign, but on whose authority has he been arrested? It is not logical, Aziz.’ Abdul Rahman was desperate to hear from his friend that what he dreaded was not true.

‘The Emergency Law and Order Administrator has arrested him,’ said Aziz who was now scanning the dial for more news. ‘I suppose you can say that we have arrested the Prime Minister. For after all, it is our General Petros Zalil who is the cause of his troubles.’ Aziz fished in his leather jacket for a pack of cigarettes. Abdul Rahman watched smoke hug the contour of Aziz’s face. ‘We should be pleased. Our ship has come in. It is our team that has won, Abdul Rahman. The secret organisations are now in charge of this country. No more worrying about the generals in the army, or that fool of a Prime Minister. You should see the way people will cringe before us after today. We are in charge now, my friend.’

‘How can you say we are in charge? I feel as if I have nothing. What do you mean? What is this about Petros Zalil? It is not normal. It is against the regulations and rules governing the structure of the state. The Prime Minister is appointed by the President. What does General Zalil have to do with such matters?’ Abdul Rahman found it hard to slow his mind; his temples wanted to explode with questions.