One of those albums that sunk like a stone. Released and then gone. Mores the pity, because this collection of 11 songs by Sierra is more than just alright.

Sierra was a single-album band of refugees from a bunch of country-rock and rock bands of the late 60s. By 1977, when their only and self-titled record was unleashed upon the buying public by Mercury, the individual players were in the sort of professional limbo that comes about regularly but is usually swept under the carpet in the biography. Which is too bad and a bit unfair, because Sierra was made up of some formidable names with very respectable curricula vitae.

Gib Guilbeau, on rhythm guitar, had played in a whole series of country-rock and proto-Americana bands like The Flying Burrito Brothers, Swampwater and the legendary Nashville West. On drums, Mickey McGee had credits as the drummer for Jackson Browne (Take it Easy), JD Souther, Linda Ronstadt, Chris Darrow, and Lee Clayton (Ladies Love Outlaws), not to mention an early country-rock outfit Goosecreek Symphony. Oh, and late Flying Burrito Brothers! Eddie’s nephew Bobby Cochran contributes blistering lead guitar and lead vocals. ‘Sneaky’ Pete Kleinow’s steel has graced hundreds of rock and country rock albums and was first brought to wide attention as a founding member of The Burrito Bros and New Riders of the Purple Sage. On bass, Thad Maxwell, another vet of the 68-75 scene, and band fellow of Gib in Swampwater. Felix Pappalardo Jr. produced and contributed piano parts. A storied figure, throughout out his life Pappalardi supported or produced everyone from Tom Paxton to Cream, not to mention his own weighty Mountain.

So, no slouches these guys. They were not suburban lads looking for a break. Their combined talent and credits were formidable. In the parlance of job advertisements they had a “proven track record” of making excellent music.

But alas, here the sum of the parts didn’t add up. Which is not to say this a shit album. Far from it. Sierra is a very good record of late 70s American pop and deserves to be hauled up from the bottom of the deep lake of forgotten country-rockers.

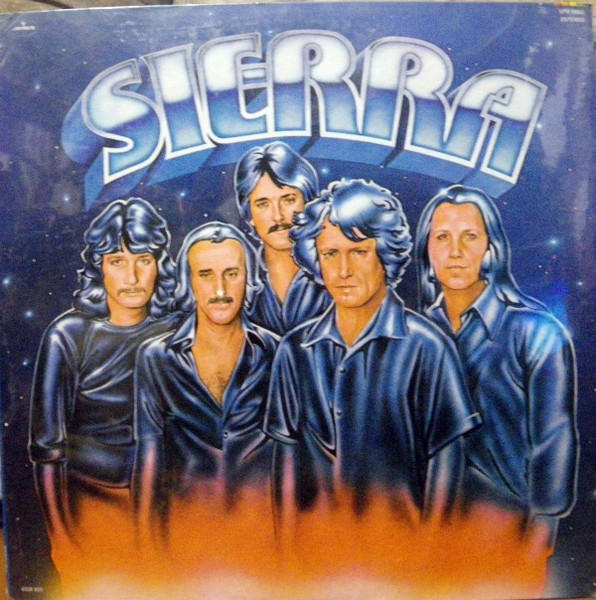

The art work is a put-off and no doubt played a big part in the record’s stillbirth. A perfect example of a cover designed by some free lance artist with no idea about the sort of band Sierra was. Many styles did they play, but spacey country-disco was not one of them. You could be forgiven however for thinking this was in fact, their speciality, if you had access only to the dumb, lifeless cover art.

On the black wax we are treated to high quality examples of soft rock (Gina; If I Could Only Get to You), So Cal country-rock (Farmer’s Daughter; She’s the Tall One), British blues (I Found Love), top 40 slick pop (Honey Dew), boogie, rock ‘n’ roll (Strange Here in the Night; I’d Rather be With You) all sauted in the spicey warmth of the Tower of Power horns. (In this era if you were good enough to entice the ToP to record with you, you were ensured at least one extra star from the reviewer.)

But it didn’t work. The album suffered not from a dearth of talent or poor production. It sank because it had no focus. Spaghetti was all over the wall, perfectly al -dente no doubt, but spread across too wide a plane. For country-rockers in search of Gilded Palace of Sin or even One of These Nights, this was bland stuff. Waaay too poppy, man!

But for this old guy living 50 years in the future, and slightly anxious about the coming extinction of human made music, Sierra deserves 7 stars out of ten, for capturing several trends of America popular music current in 1977. Especially the eternal wrestle between Country and Rawk.

There are some blatant and pointless rip-offs like You Give Me Lovin, which is essentially a copy of the Eagles, Already Gone, but what did more than the front cover to kill this album, is its refusal to rise above the very good level. The album should really have been titled, Bob Cochran and Sierra, as he is the real star. It is Bob (the only non ex-Burrito), who shows the most excitement here. His guitar is sharp and always stands out. His high-tenor voice fits perfectly in both soft rock and pop—audiences the record label was clearly trying to attract. Sadly, the band of sages behind him seem content to play perfectly, expertly, confidently but, alas, with very little real energy or pizzaz.

Ratings:

Musicianship-8/10

Listenability-8/10

Energy: 6/10

Songwriting: 5/10

Cover: 3/10

Historic Value*: 7.5/10

*a subjective ranking of combined significance & interest to the history of North American (mainly) popular music of the 1970s. Judged by myself on a particular day. Significance could include the musicians, the cover art, the producer, production quality, songwriting, influence, innovation, listen ability etc.