18 January 1990

What a rush at the airport. A huge group of Raiwindi[1]s was heading to Lahore from Karachi. It was a jumbo.

Wally met me in the drizzle at the airport and took me straight to the border. He’s pretty bummed out with the developments in the States. Berkeley has fucked him over the BULPIP directorship; hiring someone else and informing him that he was not even in the running for this year’s directorship. Wally takes these things very hard but I know I would too.

Got across to Amritsar in an Ambassador[2] which stopped every half kilometer or so due to ‘blockage’ in the fuel pump. An ansty Aussie shared the front seat with me. He was wired—shouting at the drunks, pissed off with having to pay Rs. 20 for the taxi and going on and on about missing concerts and plays back in London. Not the kind of travelling companion I want. We parted at the Railway Station.

I was greeted by 2 friends–rickshaw walas—from my last trip to Amritsar. Made a new one—a hustler who first told me there was no way I’d get a berth on the Amritsar-Howrah Mail tonight. He left and then came back after a brief interval. He suggested if I paid a little ‘chai pani’[3] I’d definitely get one. So, I paid Rs. 20 for the ticket clerk and Rs. 40 to my new friend for the luxury of a sleeper berth. A good deal. Rs. 220 for a 1879km journey.

I asked my rickshaw friends if he was a ‘gent’. Not the English term but a shortening of the word ‘agent’, used in these parts to refer to touts and fixers. “Yes”, they replied, “but an honest one. He’ll do what he says he will.” And he did.

I had asked if there were any bombings on the rails[4] these days.

They looked at me disappointingly. “This is written at the time of our birth. There is no changing it. Bombs or no bombs, when your number is up, it’s up.”

One of the rickshaw walas then broke into a parable.

“There once was a man. A mad camel got to chasing him and to escape the man jumped into a well. The camel sat outside the well and said to himself, ‘He’s got to come out one day and when he does I’ll bite him’. He settled down to wait. After a couple of days a poisonous snake slithered by and bit the camel. In an instant the camel was dead.

“The man in the well finally crawled up to have a look. He saw the camel lying bloated in the sun, rotting away. He triumphantly strode forward and gave the camel a mighty kick. His leg sunk deep into the rotting belly of the camel. The man’s leg got infected and he died.

“So, you see,” said the rickshaw wala, “even when we take precautions, Fate tricks us.”

With such encouragement I set off for Calcutta.

19 January 1990

A long journey across northern India. Lucknow, Pratapgarh, Benaras, Patna. People flow in and out of the aisles as if choreographed. It’s stuffy on the top tier but I sleep a lot. I’m surprised at the spareness of the big stations. It’s hard to find even a packet of Marie biscuits. The thought crosses my mind that maybe the great lurch into the 21st century that India Today so proudly heralds has been at the expense of the further impoverishment of most Indians.

I share a smoke with a masala magnate from Calcutta. He’s actually Punjabi but his family moved to Calcutta from Lahore over a century ago. He never goes back to Punjab.

“I like Calcutta because it’s the cheapest and safest place in India. You have no riots, no ghadbad.[5] The loadshedding is tolerable-nothing like in Benaras. The prices of everything is cheap—living, food, transport.”

He’s a real Calcutta booster. At one point to tells me, “Yes, the police are corrupt but at least a Bengali will do what he’s bribed to do. You give him some money and your work is done. It’s the honesty I like.”

He speaks in a soft voice. He begins to tell me about how he used to drink like a ‘mad man’. Always drunk. Always looking for a drink. He was, as he puts it, “at the last stage”. He then sought the help of a guru, whose name is drowned out by the clacking of the rails as we whoosh by a dark Bihari village. He pulls out an amulet with a hand tinted image of his guru. “Whatever he says, has to happen,” he quietly says. He places the image back under his shirt and against his chest. He begins relating more miraculous acts of his guru to a couple sitting next to him.

I climb up again to the 3rd tier and fall asleep.

20 January 1990

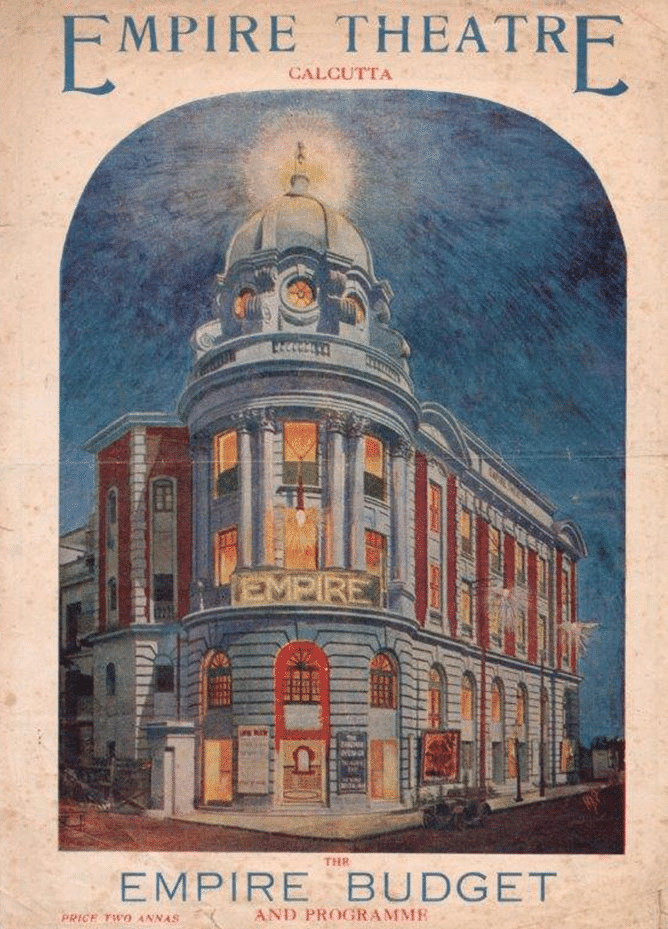

Calcutta is the city of superlatives. There is no end to the seeming premier-ness of the place. Most dirty city, most crowded. Most posters per pillar, most taxis per person. Most specialised bazaars. I saw one this morning which catered entirely to shoppers interested in balloons and rubber bands. Most cruel means of public transportation (hand-pulled rickshaws). Most diverse inhabitants, most rundown colonial buildings. Most cultured city: International Film Festivals, Classical music programs, Beatlemania stage show. Most touts. It’s hard to find anything new to say or any new superlative to add to Calcutta’s already superlative list of stellar ‘mosts and bests’.

I have found a room in the Paragon Hotel, one of these new tourist hostels which are the same no matter where you go nowadays. The Ringo Guest House just off Connaught Place is no different than the Paragon Hotel just off Chowringhee.

Tourists—Germans, Dutch, Japanese, Australians and a few frightened Americans—writing in small script in their journals, talking to each other about their similar discoveries and eating out at the same restaurants.

I walk up Sudder Street. I remember coming here, to the Red Shield Guest House[6],with my family every other year enroute to a deserted beach in southern Orissa/Odisha—Gopalpur-on-Sea.

I’m afraid to go Gopalpur these days. Afraid to find sparsely dressed Germans scowling at me as they strut around like they discovered the place.

In those days (late 60s) we seemed to be the only white faces in Calcutta. Sudder Street was quiet; New Market cool and refreshing; the Globe Theatre ran movies like The Bible. Now it shows Young Doctors in Love and New Market is crawling with sad Muslim touts begging you to buy or sell something. Hotels proliferate. Tourists swarm.

These tourists are backpackers. Young folks from the 1st world bumming around the 3rd. In Benaras they learn sitar, in Dharmsala they take a course in Buddhist meditation. In Jaisalmer they ride camels into the desert and here in Calcutta they volunteer for a week or so at Mother Teresa’s. They then catch a train to Puri or Gaya.

I admire (in a way) their altruism for washing and feeding the dying. I wish I could do the same. But something rubs me the wrong way. There is a feeling of inevitability to their righteousness. Mother Teresa is another stop along the way—like the journey of the cross in Jerusalem—full of good material to write home about. Mother Teresa is now another tourist franchise, another neat thing to do.

Calcutta is a pleasure to visit again despite the restless 1st Worlders who hang on like frightened knights of the tourist round table. The locals don’t seem to give a damn about your origins here.

22 January 1990

Spent a thrilling few hours wandering among colonial tombstones in the Park Street Cemetery (opened 1760). The image that comes to mind is a ghost ship shipwrecked on an isolated reef, forgotten and dark. Like all cemeteries it has an immediate calming effect. Jumbled and disorderly tombstones and mausoleums crumble in silent gloom among trees and hundreds of potted plants. Some of the paths are under repair but other outlying areas are as untouched as they were a hundred years ago.

I’m instantly aware this place is an entire city. Stately and expansive. Towering citadels with Corinthian columns, baths and porticos keep watch over a host of long-dead nabobs and Company servants far from home. Each tomb is grander than the next. Spires rise 6, 8, 10 feet above the soil in honor of a young civil surgeon downed by ‘fever’ or an indigo planter consumed by the pox. The most ordinary of India’s first British colonizers have erected over their bones and spirits structures few Presidents can boast.

The Raj was young when Park Street opened. The Battle of Plassey was only three years won. Young men with no social standing back home, here had a chance to be rajahs off the plentitude of Bengal. These young men had never dreamed of the fortunes to be made in Bengal; Bengal had no way to stop them. Park Street memorialises the sense of destiny and ostentation of the early Raj. The world was waiting to be plucked from the mohur trees. Fortunes were huge and readily won for those who showed their ruthless ambition. For them this was a larger-than-life world. I suppose a bereaved father felt it perfectly natural to raise a small Roman temple in honour of his nine-month old infant son, dead by flux. The cemetery, like the period, like the characters buried here is an overstatement. The epitaphs are sentimental and overegged. There was never a disliked, cruel or greedy person buried here.

Of course, not everyone buried here is insignificant. William Jones, the great Orientalist icon who was the first to propose the idea of a shared kinship between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin, lies under a 15-foot obelisk. Charles Dickens’ second son has been lovingly moved here by students from Jadavpur University. Richmond Thackeray, father of William Makepeace Thackeray, a senior servant of the Company, lies here, as does the wife of William Hickey, India’s first prominent English journalist.

Teachers of Hindoostanee at Fort William College, traders and fair maidens, Park Street Cemetery is, more than any other place in India, a memorial to the Raj. Here one can taste the self-aggrandisement, the self-importance and most of all, the self-pity which characterises British India. You only need to close your eyes to hear them speak again. Little do they realise that their ostentatious moments of death are long forgotten and ignored.

23 January 1990

Today I arrived in a cemetery of a different sort. The great ancient temple city of Bhubaneshwar. An initial quickie around the city has left me awed with the grandeur of India—truly the Wonder That Was. I’m none too impressed however by the greedy mahantas and pundits who follow me with visitor books filled with the names of foreigners who have come before me and donated Rs. 100 or 150. They are like blood suckers who will not detach themselves from you until you fork over some cash. Muttered curses follow me when I hand over a fist of Rs. 2 notes or a tenner. “You should give at least Rs. 50,” one calls out as I walk away.

24 January 1990

Had a sleepless night. The bed in the Janpath Hotel was infested with bedbugs and the room abuzz with mosquitos. I was so tired and on the verge of the final descent into sleep only to be woken by a damn katmal gnawing at some remote part of my body. The room was distinctly shitty. A weak but persistent stench wafted across the room. No windows, only some cement grating at the top of the wall which allowed easy access for the mosquitos.

I flung my few large pieces of cloth on the floor and turned on the fan. I caught a cold and my neck ached but I must have fallen asleep between 2 and 3.

I blearily wandered off toward the Lingaraja complex which was still as impressive as it was yesterday evening. The priest left me alone to take some photos. I met two young pandas[7] who were only interested in chatting, not in extracting money from me. One was Kuna and the other Bichchi. Kuna kept classifying women into a personal scale of ‘sexual’. “Western lady very sexual”, or “Japanese lady most sexual”. He was full of obscure English aphorisms. “Every book has a cover every woman a lover”, was his favorite but others addressed less sexual subjects as well.

Bichchi was interested in telling me about politics. One of the Patnaik[8]s was in power. Another Patnaik was trying to squeeze him out now that he (the second Patnaik) had the leverage of the National Front government in Delhi. Bichchi was confident that his Patnaik (the second one) would be victorious in the end. The main complaint against the ruling Patnaik was that—as best as I could understand from Bichchi’s broken Hindi—he liked to consort with little boys. If not that he drank or smoked something that wasn’t good.

Kuna immediately spoke up. “Is there only one tiger in the jungle? They all do these things. Have you ever seen only one tiger in the jungle?”

They tried to encourage me to drink some bhang[9]. Being already light-headed from a sleepless night I declined. They extolled the virtues of bhang but cursed heroin, charas [10]and alcohol. All these vices Bichchi attributed to the Pakistanis. He saw a nefarious attempt to destroy his country. Apparently, there are in Bhubaneshwar a growing number of drug addicts.

Kuna again offered his own interpretation. “It is good. We have 90 crore[11] people here in India. If a few kill themselves with heroin good. It will keep our population down.”

I took my leave after an hour under the shade of the Lingaraja, one of 125,000 temples said to be scattered around the city. This statistic came from Bichchi. I was tired and wanted to nap but didn’t want to do it in the Janpath Hotel. Over a beer at the Kenilworth Hotel, I resolved to head immediately to Puri in search of cleaner mattresses and an airy room.

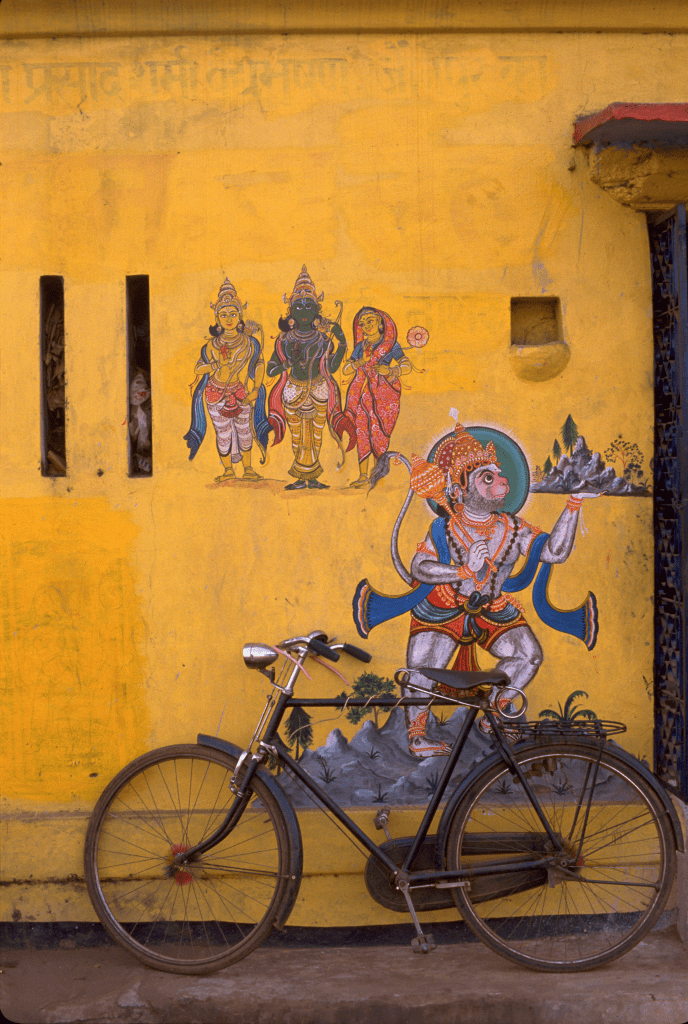

25 January 1990

Puri strikes me as an overgrown seaside fishing village. Except for the fact that it is one of Hinduism’s four major dhams[12], there didn’t seem much to commend the place. The beach is here too, of course, but it has none of the isolated charm of Gopalpur or the lushness of Kovalum. The alleys are dark and damp and only Hindus are permitted to enter the ancient Jagganath[13] temple. For a photographer it is also frustrating. The temple is set at an awkward angle which makes it almost impossible to capture well. The square in front of the temple is in glaring light most the day so people huddle in the shadows under the tarped awnings. After walking around searching for some good light, I put my cameras away. From now on I’ll stick to the alleys where little icons and shrines add color to the landscape.

I talk with Mohammad Yusuf who is selling reptile scales for the cure of piles and general unwanted blood flow. He makes rings of these and advises his customers to wear them on their left hand so as when they perform their toilet, the rings’ magical effects will “make you 100% clean. You can spend Rs. 10,000 on a doctor but these rings will cure you completely.”

He is an Oriya[14] but like most Muslims in the north speaks quite good Urdu. When I told him I was living in Pakistan he quietly asked, “What’s the news? Is it good?” I find the Muslims I’ve run into –a lot—to be sad people, though I’m probably projecting. In Calcutta all the booksellers and tape hawkers on Free School Street are Muslims from Howrah. One told me with a bit of over enthusiasm that “Hindus are the best. I have more Hindu friends than Muslims. We have no problems here!”

Another, Salim, is a waiter at the Janpath Hotel in Bhubaneshwar. He was soft spoken and left me with a feeling tender. He claimed to make Rs 200 a month in the hotel of which $150 he remits to his family. He used to work in Calcutta in a factory that makes cooking utensils but for some reason came, as he put it, “into the hotel line.” He doesn’t like the work but is stuck. He saw two postcards I had bought from a sidewalk dealer on Sudder Street. One was of the Kaaba[15] the other was of Imam Hussain on his horse. Salim kissed them and pressed them against his forehead when I offered them to him.

The Muslims seem to be accepted and other than a slight hesitation before telling me their names, they seem content. They confess to cheering for Pakistan’s cricket team but have been quite uninterested in asking me about life in Pakistan. Only one, a cloth merchant in Bhubaneshwar, asked me if I preferred India or Pakistan.

Tomorrow, I take a day trip to Konarak. It’s Republic Day and will be overrun with tourists undoubtedly.

26 January 1990

I was accompanied to Konarak by a Gujarati, Dr. Parwar. A pleasant and gentle man who had pulled himself up to a position of considerable rank and authority in a government hospital. His father was a manual labourer in Pune, “so I have seen life from close up.” Through hard work he got his MBBS and MD from one of the best medical schools in India and has since added a triad of MA’s in subjects like Public Health, Venereal Diseases and Administration. He has been attending a conference in Calcutta on Public Health Administration and has come to Puri to kill some time.

He is deeply committed to serving the people of India as a doctor back in Ahmedabad. He has no desire for an overseas job or money. He proclaims more than once how proud he is of being Indian. This is not something I hear in Pakistan very often.

Konarak is impressive. The stone sculpture is beautiful and majestic. The monument is set out as a sun chariot with 24 giant wheels pulled by 7 rearing horses. Most of the original temple has been destroyed but the remaining bits inspire awe for their size and beauty. The original temple rose more than twice as high at the remaining remnant which rises 80 feet into the air.

Dr. Parwar and I climb to the top of the temple and gaze into a deep opening. A pedestal is at one edge where we overhear a guide explain, “This is the place where the image of the Surya (the Sun God) stood”. Inside his stone head and feet, apparently, was magnet which when a certain interaction of physics and metaphysics transpired “caused the God’s head and feet to move.”

The Indian government is preserving the temple. Dozens of lungi[16] clad workers scratch the eroded stone with water-soaked bamboo brushes. Here and there new plinths and slabs of granite have been fitted into the chariot spokes and walls. Up near the top they have placed two huge Buddha-like images, upon which, during the Eastern Ganga dynasty[17] which built the temple, the sun was said to have shone continuously. One at dawn, one at noon and one at dusk. The third image is yet to be restored.

Dr Parwar and I silently take in this magnificent piece of human-divine cooperation before boarding a bus back to Puri.

[1] Raiwind, a town near Lahore, famous as the headquarters of a major Islamic missionary organisation, Tablighi Jama’at

[2] Hindustan Ambassador. Iconic Indian manufactured sedan which for decades was about the only car available in most parts of India.

[3] Literally, ‘tea water’. Colloquially used to indicate a small gift/bribe.

[4] A Sikh movement for Khalistan as a separate country was raging in the 80s and early 90s. Often trains passing through Punjab were bombed as part of the terroristic tactics of militant Sikh groups. By 1990 things had calmed down quite a bit but my question was not entirely unjustified.

[5] Hindi/Urdu word meaning ‘chaos’; ‘confusion’; ‘disorganisation’. Colloquially, ‘hassle’.

[6] Part of the Salvation Army’s global charity empire. Cheaper rates for Christian missionaries right in the heart of Calcutta!

[7] Hindi word for priest or guide to a temple. Not the Chinese animal.

[8] A prominent political dynasty in the state of Orissa/Odisha.

[9] Traditional Indian cannabis drink.

[10] Hashish

[11] Hindi/Urdu for the numerical value of 10,000,000

[12] The four dham are the major Hindu pilgrimage destinations located at each cardinal point of the compass. Dwaraka (West), Puri (East), Badrinath (North) and Rameshwaram (South)

[13] From which we get the English word, juggernaut.

[14] A native of Orissa/Odisha

[15] The stone building at the center of Islam’s most important mosque and holiest site, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia

[16] sarong

[17] 11-15th century CE