In 1996 I visited Afghanistan and Pakistan for an Australian NGO. The Taliban had just captured Kabul a fortnight earlier and thrust, very momentarily, the plight of everyday Afghans back into the international media’s spotlight. Given the current state of Truskland I think these voices are worth revisiting.

He was as new to town as I.

“I came here from Kabul the day before last. My name is Hashim.” He wore a hesitant smile and a blue waistcoat. He had been watching me walk up through the gardens and toward the street. “Will you make my photo?” he asked.

He posed with his arms across his chest and gazed away from the camera with a cinematic expression. I took his picture and asked what had brought him to Mazar-e-Sharif.

“My father told me to get of of Kabul as the Taliban are capturing all young me to fight. I’ll go back when my father tells me. I am staying in a hotel as I have no relatives in Mazar. Its very expensive. All day I sat here watch people in the garden. I sit and think but I try not to think of my family. We had a shoe factory in Kabul. But when the mujahideen came to power they stole everything. Now I am jobless. In Kabul I study English and also kung-fu. But now everything is closed. I don’t go out because it is too dangerous. I am Turkoman. The Taliban are against us. And the Tajiks and Hazaras.

“I saw Najibullah hanging in the street. It made me sad. None of these groups are Muslims. They only kill anyone who doesn’t agree with them. ‘Grow a beard!’ ‘Wear a hat!’ ‘Don’t go outside!” And if you disagree to grow a beard it is the end. For the last 5 years I have seen these people. They are not Muslim.

“See that man there, singing. He’s gone mad. I’ll go mad, too. I sit here everyday. I want to get out of here, to Germany or to an English speaking country but its too expensive.”

*****

“How is my English? I have been studying for two years but most foreigners do not like to speak with me. Why is that? One time I asked a foreign man what time it was. He told me, ‘Sharp 4 o’clock!’ That was that. He said no more to me.” Khaililullah spoke excellent English. He was a northern-Pashtun–dark, almost Indian in appearance. But he had born north of Mazar and had recently returned from over 10 years as a refugee in Pakistan.

“I teach English. In Monkey Lane. Will you come and visit our class?” I told him I would come but not today. Today I was interested in visiting the shrine of Ali, the grand blue-tiled mosque around which this desert town spills. I told Khalilullah how much I admired the mosque and its color. “You’re lucky to live so close to such a beautiful building.”

“By the grace of God we have a good leader. General Dostum. He used to be a communist but now he prays five times a day–he’s very good. And powerful. The Taliban are the trouble. They want to keep girls from school And this forcing men to pray in the mosque five times a day. Even our Prophet Mohammad himself only prayed 4 times a day sometimes So who are they to force us?

“Of course. There were excesses in Najib’s time. He gave too much freedom and too quickly. Especially to women. This corrupted us. Women went about barefoot–without shoes and wore nothing at all on their heads. According to Islam, a woman’s head should be covered. But not completely hidden. Both the Taliban and Najib are wrong. God save us from that much freedom. On the other hand under Najib, women and girls were educated and worked. That was good. So he was not entirely bad.”

Najibullah felt that the public hanging of Najibullah was inevitable. In his mind it was a justice of sorts for having allowed women to go barefoot and to be judges. But what he told me next I heard many times during my visit.

“Before they killed him they ordered him to sign his own release papers. He refused. He had denounced communism and discovered patriotism. He did not feel he had to confess to any crimes. But I know from an accurate source that he had memorised the entire Quran. But he refused to sign the papers confessing to anything. So they killed him. But in that, he was right. All Afghans respect Najibullah now. He wasn’t afraid to die. He was a true Afghan.”

When I visit Khalilullah’s school a few days later he refused to discuss anything except English and non-political subjects. “What do you call this?” he asked me, pointing to a shelf. He made not of my response, “A mantel.”

He and his fellow students discussed music and literature as if nothing was wrong with their country. The school had 600 students, women and men, learning English every day. “We want to prepare ourselves for the future. Today you must have knowledge of two things, English and computers, if you want to succeed.”

Jamil was adamant. “What do you believe will happen to Afghanistan?” Before I could respond he went on. “We are fanatics. This is no way to bring universal peace anywhere. And there is no way our people will talk. No way they can win in fighting either. I don’t know what will happen. This fighting will continue. All I know is that I will go to English class and then I’ll go home. Tomorrow? God only knows. Who sees beyond today? We are ready for anything though. My father is not a commander. We are civilians. We want peace and normality. Things like sports and music. My name is Jamil. It means beautiful. We want to help ourselves by learning English but our pronunciation is all bad. What do you think?”

*****

*****

“Welcome! Just have a look, no need to buy.”

The huge bearded Afghan stood beckoning to me from the doorway of his carpet shop in Peshawar’s Khyber bazar. It was a typical sales pitch but it soon changed when I enquired about the man who owned the shop next door. He was the son of a friend from Melbourne.

“You want to see Hamid?” he glared at me.

I nodded.

“Communisti!” The word hissed out of mouth like air leaving a tyre. His companions in the shop immediately turneds toward me and smiled sheepishly.

“Hamid is no good man. He is a foreigner. And communist. He supported Russians and speaks their language.” The man stumbled about for words to express his dissatisfaction with his neighbor. He spoke broken English and felt limited in what he could say.

“Communists. Uzbeks. Hazaras. Very bad.” He made a gesture with his finger slicing across his neck. “They are not Afghans. They are Angrez!”

I asked what he meant by calling Uzbeks and Hazaras, the most Mongol-featured of Afghans, Englishmen.

“He means they are foreigners. They have come to Afghanistan only recently. They are not true Afghans. We Pashtuns are real Afghans. The others are not. They are so small in number, not like us. Pashtuns are 60% of Afghan people. The others are only few. Miniorities, you know.” This man who spoke better English wouldn’t tell me his name but he did identify himself as working as a ‘spokesman’ for the Taliban office in Peshawar. “I know very well the Taliban. They are very good. They are against Communism and foreign domination.

“You see, we are refugees in Pakistan. It is not good for us to say that we want to control Pakistani politics of government. This is not our right. We should only sit quietly and do our business. It is not right for us to force our desires on the Pakistani public. And so it is with Uzbeks and Tajiks–though Tajiks are not so bad. But Uzbeks and Hazaras. They are refugees, not true Afghans. They came only in the last 40 years and now they want to dominate the whole country. But it is for us Pashtuns to control Afghanistan. This is our country. Uzbeks should return to Uzbekistan and Tajiks to Tajikistan. Why should they stay in Afghanistan?”

The bearded carpet seller broke in again. It is very dangerous here these days. Every day the Shi’a are attacking Sunnis. We must kill the Shi’a.”

Most Hazara Afghans, the poorest and historically most discriminated against of all Afghan minority groups, are Shi’a.

The TV in the shop began broadcasting an old Pakistani film romance. The men ignore me and lay down on the carpets in front of the TV. A woman danced through a rose and fountain garden to a lively folks tune. The men smiled as they watch the star dance.

I didn’t bother to ask them about the Taliban’s attitude toward women.

*****

The next day I had tea with an Afghan refugee family. They had come to Pakistan after the fall of the Najibullah government in 1992. They were secular, non-Pashtun Afghans. Educated abroad and middle class. For four and a half years they had lived in Peshawar.

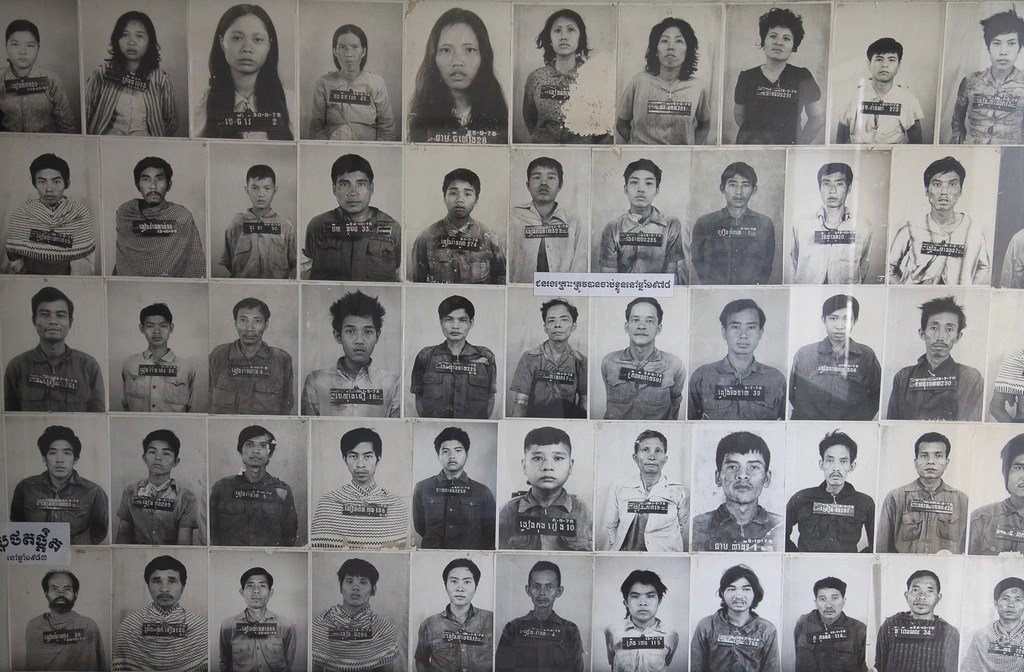

The matriarch of the family, Hafeeza (not her real name) has lost a husband, two sons and two daughters. Her husband, a senior figure in the PDPA (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan), the Soviet-backed party that ruled Afghanistan from 1978-1992, was assassinated in 1989. Her eldest son and daughter were kidnapped in 1992 by triumphant and vengeful mujahidin in Kabul. “I have no idea why they were taken from me. These people hate everyone…especially people who they consider communists or Russians.

“My eldest daughter was a doctor. Since the day of her marriage I have not seen her. She may be dead. Or she may be living secretly someplace. But I’m sure she is dead because even if she was in Mazar or overseas she would contact me.”

Hafeeza had been the principal of a large school in Kabul. In Peshawar she had tried to get a job as a teacher but had been turned from every door, called a communist and foreigner. “I have even tried to have young children come here to our house for tutorials but parents forbid their children from attending because they believe I will teach them wrong things.”

She smiled ironically. Another member of the family took over. “In the schools here in Peshawar, which are controlled and run by the mujahidin and Taliban, Afghan children are taught to kill people like us.”

She puled out a text book which looked like any normal grade-school primer. Poorly drawn figures and large simple sentences filled each page. Instead of apples and kitten the lessons used AK-47s as object lessons. 1 Kalashnikov plus 2 Kalashnikovs equals how many Kalashnikovs? On the following page, a similar arithmetic problem used grenades.

“What will happen to our children? What is the future of our country if they are taught such things? They are taught to hate and kill. Their masters in school teach them that if they kill 3 Communists or kafirs they will become ghazi. No wonder they hate us. Our lives are in danger. We cannot get work and we are afraid to move about in the streets.” Hafeeza broke down.

The other family member told me, “Just six weeks ago, her only remaining son was kidnapped here in Shaheen town. He was going to an English class be he never returned. He had been threatened and warned by some bearded people a few times, ‘we know who your rather was. You are a communist and Russian.’ Hafeeza asked him not to go out but he was young and wanted to learn something. But now he’s gone and I’m sure he’s dead.”

Hafeeza stared blankly at the floor. Her only remaining child, a 19 year old daughter, comforted her mother, though she herself was in tears. “They do not go out at all these days. They are afraid after what happened. Who will protect us? We are not communists and we are not Russians. Our fault is we are not Pashtun and we oppose the Taliban. For this they want to kill us.”

The family has siblings and parents in Melbourne. But their repeated attempts to get visas to come to Australia have failed.