Lollywood: stories of Pakistan’s unlikely film industry

This brings to a close ‘the background’ story of Lahore. The next sections will deal directly with the movies and movie-making culture of Lahore.

Bahut ghoomi ham ne Dilli aur Indore ki galiyan

Na bhooli hai na bhoolengi Lahore ki galiyan

Yeh Lahore hai Punjab ka dil/Jis zikr par aank chamak uthi hai dil dharak urdthe hain

I’ve roamed the lanes of Delhi and Indore, but I’ve never forgotten nor ever can forget the lanes of Lahore. This is Lahore. The heart of Punjab whose very mention causes the eye to sparkle and the heart to skip a beat

These opening lines of the 1949 Indian film Lahore sum up the deep affection and nostalgic sentiment millions of South Asians feel for the city of Lahore.

**

Lahore, modern Pakistan’s cultural capital, is one of those cities that lives in the very soul and DNA of its residents. Like a handful of other cities across the continents it occupies a place not just on the map but in the imagination of those who know it. It is at once an indivisible part of people’s self-image and something beyond capture. As residents of the city say, Lahore, Lahore hai (Lahore is Lahore). So profound and all encompassing is the city’s essence that the simple acknowledgement of its existence is enough to conjure an entire world.

There’s a small but passionate genre of writing that centres on the city. Novelists, poets, journalists and emigres, displaced at the time of Partition, wax lyrical in their books and gatherings in praise a city they all remember as sophisticated, vibrant, classy, tolerant, full of tasty food, and shady boulevards. Its fabled history and stunning architecture. It’s unique urban culture. If, as they say, nostalgia is a narcotic, then Lahore is one of the subcontinent’s biggest addictions.

It certainly is an ancient city and the millennia have added a depth of colour and richness that most other cities can only envy. But Lahore has also experienced long periods of cultural and physical devastation when the city’s palaces and shrines were little more than crumbling ruins. When its resplendent gardens lay overgrown and unattended. And it was this sort of Lahore that the East India Company’s redcoats grabbed away from the Sikhs who had ruled Punjab for much of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

After ‘annexing’ Punjab, the British set about rebuilding Lahore. Though the Sikhs, under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, had added some new buildings and gardens to the old city, in general the once glorious imperial city, famous throughout the world for a thousand years, was in an awful state. Amritsar, 80 kms to the east was the Sikh’s spiritual home and a booming commercial hub; Lahore, their world-weary political capital. Important more for what it had once represented—the imperial grandeur and awesome power of the mightiest Empire of the medieval world– than what is now was: a cramped, unhygienic, walled city down on its luck.

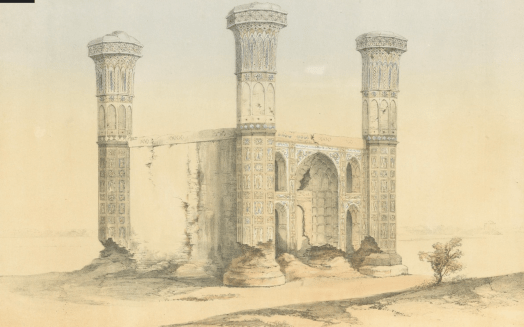

At the time the British narcotic-peddling businessmen defeated the Sikhs in February 1849 the suburbs surrounding the old city were little more than ruins. “There is a vast uneven expanse interspersed with the crumbling remains of mosques, tombs and gateways and huge shapeless mounds of rubbish from old brick kilns,” wrote an Englishman who visited the city around this time. Though the Sikh sardars had not gone out of their way to destroy existing Mughal-era buildings they displayed no hesitation in stripping the creamy, jewel-encrusted Makrana marble off the walls of the tombs and palaces to adorn their own havelis.

More than with other cities, the British sensed that in Lahore they had indeed captured a jewel. Milton’s reference to the city in Paradise Lost had been rather cursory. More elaborate and accessible was Thomas Moore’s Orientalist fantasy Lalla Rookh which in the early 19th century had become hugely popular across Europe. Based vaguely around an imagined romance of a Mughal princess in the time of Emperor Aurangzeb (1658-1707), the poem introduced the name and idea of Shalimar into Western consciousness.

They had now arrived at the splendid city of Lahore whose mausoleums and shrines, magnificent and numberless, where Death appeared to share equal honours with Heaven would have powerfully affected the heart and imagination of Lalla Rookh, if feeling more of this earth had not taken entire possession of her already. She was here met by messengers dispatched from Cashmere who informed her that the King had arrived in the Valley and was himself superintending the sumptuous preparations that were then making in the Saloons of the Shalimar for her reception.

The development of Lahore into one of British India’s premier cities—and a place where a sophisticated industry like movie making could thrive– has to be understood as part of the development of British rule in India. The great riverine plains of Punjab–a stretch of geography that historically included Delhi at the eastern edge and touched the Afghan border in the west–were the last big chunk of agricultural land available in northern India. They marked the final frontier of British India. The Empire’s very existence not to mention the Company’s business model depended on a perpetually growing revenue base collected primarily from raw agricultural products and oppressive taxes on those who worked the land. By the time they reached the Punjab, the Company was the unassailable political and military force in politically fluid landscape. But at the same time, their purely extractive approach to governing had reached its limits too. Beyond Peshawar, a largely Afghan city but in the early 19th century an important Sikh holding, towered the rugged mountains of the Hindu Kush, the historic barrier dividing South from Central Asia. These were a useful security asset but absolutely bereft of economic value.

Soon after wresting control of Punjab the English were confronted with the first substantial resistance to their rule. In 1857 soldiers in the employ of the British East India Company ‘mutinied’ and for over a year engaged their European masters in an armed conflict that engulfed much of north India, saw the destruction of Delhi and the final collapse of the (by this time, entirely symbolic) Mughal Empire. A shocking number–800,000–Indians lost their lives either directly or indirectly as a consequence of the uprising. The European community estimated at around 40,000 in all of India at the time, lost about 6000 people. Though a much smaller number, proportionally it meant that about 1 in every 7 Europeans perished. If it did nothing else, the war exposed the underlying vulnerability and inherent instability of European rule in India. And though they would rule for nearly another century, everything that happened in India after 1857 in some way can be seen as a reaction or delayed response to the conflict.

Though the uprising was ultimately quelled the British were shaken to their core. The East India Company, which over the previous 150 years had demonstrated itself to be little more than a rapacious business enterprise intent on asset stripping the richest country in the world was disbanded by an act of Parliament. India was reconfigured as a Crown Colony under the direct purview of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. The British realised that things had changed. And if they were to continue to benefit from their Indian Empire they would need to experiment with different management techniques including setting up a system that at least appeared to take some interest in good governance rather than simply syphoning off India’s great wealth. One of the immediate, visible signs of the new era was the rise and promotion of the Punjab as a ‘model’ province. A place where the noble intent and attributes of a Pax Britannica could be readily demonstrated and accessible.

Punjab was a vast piece of land but it was by no means uniform. The eastern and to some extent, central districts of Punjab were rich, well-watered agricultural lands with relatively dense populations. The much larger western part of the province spreading out towards the northwest and southwest of Lahore were arid, sparsely populated and agriculturally unproductive lands. In terms of the colonial economy, eastern Punjab was valuable; the west, not so much.

It didn’t take long for the administrators of Punjab to understand that this was unsustainable. It wouldn’t be long before the eastern/central portions of the province would be overpopulated and the land overused. Productivity and more importantly, revenue for the British Exchequer would fall. Also, never far from British minds was the prospect of rising social tensions that an unmet demand for land represented. No one wanted to risk another 1857. Especially not in the land of the fabled Sikhs, who had been consistently lionised by the British as a great “warrior race” and upon whom they were banking to be the backbone of their own security and military apparatus. To use contemporary language they needed to keep the Sikhs sweet.

And so, beginning in the 1880s, with the intention of keeping the Sikhs happy and the Punjab prosperous, the government tilted imperial policy in Punjab toward investment rather than mere extraction. The vast, underutilised and dry western tracts of the province became the focus of a massive economic and social experiment. Construction began on a network of massive canals that diverted water from the Jhelum and Chenab rivers, that by 1920 had turned 10 million acres of ‘formerly desert lands, most of which had been the hitherto uninhabited and worthless property of the Raj’ into some of the richest agricultural land in India. Six districts including the rural areas around Lahore experienced a demographic and economic revolution as hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Hindu and Sikh farmers, were encouraged to move from the eastern parts of Punjab to the west. They settled in new purpose-built towns along the canals to produce wheat and cotton on a scale India had never seen before. And as the biggest city in Punjab (and the largest between Istanbul and Delhi) Lahore itself, the urban hub from which the new Canal Colonies were managed and supported, entered a fresh era of prosperity.

Reimagining Lahore

From the moment the Sikhs were defeated, the British set about rebuilding the crumbling historic city they had inherited. The new administrators were bewildered and not a little intimidated by the old walled city, which they left largely to its own devices. Instead, the English concentrated on the ruins that lay outside the walls. With a fearsome industriousness they cleared the plain to the southeast and laid out a European style suburbia. Christened Donald Town after Donald McLeod, an early Lt. Governor of Punjab, the main thoroughfare in this new part of town was christened McLeod Rd. On either side, a residential and business area for Europeans sprang up including an important and large military base or cantonment, further south in Mian Mir. By the 1930s, the place where McLeod Road crossed Abbott Rd, a junction called Laxmi Chowk, would become (and remains to this day) the central locus of the city’s film industry.

Between 1860 and the early 1900s Lahore found new life as a hugely important regional centre for education, communications, publishing and culture. Delhi, the age-old capital of northern India had been savagely destroyed during the fighting of 1857. The city’s famous tribe of musicians, writers, poets, artists and thinkers fled the capitol in search of more secure places; some headed south to Hyderabad and others east to Lucknow. And with its newly acquired territory in the northwest the British government deliberately identified Lahore as an alternative cultural hub to which they encouraged émigré artists and intellectuals to settle.

Several prominent Urdu language writers and poets did move west to settle in the city where educational institutions were springing up under official sponsorship but also with the investment of wealthy Punjabi landowners and businessmen. Though the city had no real affinity with or history of speaking the Urdu language, a combination of official policy and organic economic development saw Lahore become one of India’s most important Urdu centres. Though the city’s residents continued to speak their beloved Punjabi, using Urdu only for official work or to get a job, Lahore was transformed rather quickly into a bi-lingual town. Their easy facility with both languages and often with English as well, in time would give Punjabis a huge advantage in the nascent Indian film industry.

Lahore’s publishing and printing industry produced newspapers, books, religious texts and magazines in multiple languages including Urdu, English, Persian, Punjabi but also Arabic and Sindhi. The city, already famous for its literary culture, refreshed its traditions with poetry recitations called mushaira which drew poets from across north India as well as significant audiences from the city’s many colleges. By the turn of the century a hundred or more newspapers were available across the Punjab most of which were in Urdu including many published in Lahore, such as Kohinoor, Mitra Vilas and Punjab Samachar. In addition, though catering to a much smaller audience, but widely read and highly regarded were two English dailies, The Tribune and the Civil and Military Gazette, most famous today for it’s most famous resident journalist, Rudyard Kipling.

The number of prominent Urdu writers who were born, educated or settled in Lahore is too vast to mention: Agha Hashr Kashmiri, Taj Imtiaz Taj, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Hali, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishen Chander and of course, in the last years of his life, Sa’adat Hasan Manto many of whom developed a connection with both the local and national film industries.

Northwest India’s educational Mecca

In the late 1830s and 1840s the British laid out the basic parameters of an education policy for India. The ultimate purpose of the policy was very much in keeping with the political agenda of the EIC which was all about control, avoidance of undue investment and efficiency of administration. As such, to the extent that official British efforts were to be focused on educating Indians, it was as a means to advance the Company’s and then Britain’s, commercial and political ends: to create a loyal group of Indian elites who would be conversant in the English language, imbibe European values and culture and be dependent upon Official patronage. In the famous words of William Macaulay a senior and prominent 18th century administrator of the Company, “we must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern.”

And to that end government efforts were to be focused on developing and supporting a system that preferenced higher education as opposed to mass primary education and which was to be delivered entirely in English through institutions modelled on those in Britain, especially the great universities in Oxford and Cambridge.

By the time the final piece of the India puzzle, Punjab, was tapped into place these ideas were fresh in the minds of the English. And so, in keeping with their intent to make the province an exemplar of the colonial project, Lahore was developed into the premier educational city of northwest India. Beginning in the 1860s and continuing up through the first decades of the 20th century, the British supported or sponsored the establishment and development of a number of colleges that became famous as some of the best in India and whose alumni included several generations of elite leaders including multiple Prime Ministers of both Pakistan and India.

Schools like Forman Christian College, founded by an American missionary in 1865, and Government College a year earlier, provided English/Western education to the first generation of Punjabis to live under British rule. These schools were complemented by pioneering medical training colleges (King Edward Medical College) or absorbed into more prominent larger institutions like the University of Punjab in the 1880s. Secondary colleges, especially the world-famous Aitchison College (1864) prepared the young sons of the princes and the landed aristocracy of the Punjab to enter the elite colleges and ultimately, service in the bureaucracy. Being educated in Lahore became almost compulsory if you wanted to pursue a career in business, science, government or the arts. Students came to the city from all across the northwest and in the 1930s Lahore was said to have a student population of nearly 100,000 students enrolled in 270 colleges and schools.

Actor and Hindi movie superstar Dev Anand and his equally talented brothers came to Lahore from Gurdaspur in the east to be educated at Government College, part of the University of Punjab. At the same time, from Rawalpindi further to the northwest, came Balraj Sahni, who established himself as one of India’s finest cinema artists after the Partition. We could fill several pages with the lists of prominent politicians, sportsmen and academics, not to mention military leaders who graduated from Lahore’s elite schools but just a few provide a flavour of the quality of education the city provided. Imran Khan (former Prime Minister of Pakistan and international cricket star), Abdus Salam (1979 Nobel Laureate in Physics), Inder Kumar Gujral (Prime Minister of India), Pervez Musharraf (President and Chief of Army Staff of Pakistan), Allama Mohammad Iqbal (writer and philosopher), Kuldip Nayyar (prominent Indian journalist), Krishen Chander (pioneering Urdu writer), Har Gobind Khorana (1968 Nobel Laureate in Medicine) and Faiz Ahmed Faiz (modern Urdu’s greatest poet).

While Dev Anand and Balraj Sahni were able to attend the elite colleges most of Lahore’s film industry personalities were either educated on the job in the studios and sets or attended a set of schools established to cater to the middle class Hindu and Sikh communities who controlled Lahore’s economy. Schools like DAV College founded by the reformist Arya Samaj educated tens of thousands Hindu and Sikhs. Islamia College, long associated with Allahabad University, offered higher education to Muslims who were a little more sceptical of attending the heavily westernised University of Punjab or Forman Christian College.

The learning environment of Lahore extended to female education as well and the city had a reputation for its relatively progressive attitude towards women participating in public life. Kinnaird College, established by missionaries in 1913 as a counterpart to Forman Christian College, educated the daughters of Punjab’s best and brightest families. Writers Bapsi Sidhwa and Sara Suleri, academics of all disciplines, the human rights lawyer and campaigner, Asma Jehangir and Hindi film actress Kamini Kaushal all graduated from Kinnaird.

Migrants, not only from eastern Punjab but the rest of India came to Lahore to get in on its vibrant economy and cultured society. By the 1920s the city was known not only as a premier destination for higher education but a city of ideas. Hindu reformist movements such as the Arya Samaj and Brahmo Samaj, from Bombay and Calcutta respectively, found fertile ground in Lahore and in the case of the Arya Samaj enjoyed significant growth and popularly in the city.

Political flashpoint

The many educational institutions created an environment in which ideas of all sorts were traded, debated and contested; Lahore slowly gained a reputation as a political hotspot. The British policy of building up a class of loyal Indians ready to fight for the Raj may have been the stated outcome of education in British India but too often things don’t go exactly to plan. With so many students enrolled in hundreds of schools things were bound to get out of control.

In response to the missionaries’ evangelising, each of Punjab’s three major religious groups took upon themselves to reform their own faiths turning Lahore into a site of new self-styled progressive religious teaching. Though founded in Gujarat to the south, Lahore became the main centre of the Arya Samaj, a Hindu reformist group which championed education, women’s participation in public life, a return to Vedic Hinduism as well as an aggressive anti-Muslim, anti-Christian stance. Many of the Hindu middle classes of the city were attracted to its teachings and sent their children to the Samaj’s schools and the influential D.A.V College.

Initially, middle class Sikhs were welcomed and participated in Arya Samaj activities but eventually split from the movment over, among other things, the Samaj’s aggressive campaign of mass reconversion of rural Sikhs to Hinduism. In response, the Sikh community sought to distinguish themselves from the Arya Samaj and began preaching a more exclusive and purist form of Sikhism which focused on the reformation of the government-sponsored ‘clergy’ that controlled Sikh places of worship. The Akali Dal, a group that arose out of activist Sikhs, many from the new Canal colonies, quickly took on an anti-British political agenda which the British promptly labeled as a greater threat to the stability of Punjab and India then Gandhi and the Congress Party. The Sikh Sabha and Akali movement was active across Punjab but especially in Amritsar and Lahore, whose branch was seen as the more radical and political.

Several Muslim communities found themselves developing new identities and leaders too. in the 1930s and 40s, the rural agricultural Muslim communities bounded together with similar rural groups to form a loyal pro-British political coalition. But other groups, such as the Ahrars, established in 1929, articulated a strong anti-British, nationalist and anti-feudal agenda. At the same time, it spearheaded a religious reform agenda that among other things was the first to demand that the small but successful Ahmadiya community be declared non-Muslim.

Though reform and purification of faith were the starting point of all these movements, by the 1920s they had blurred the line between religion and politics. The British kept close tabs on them and openly interfered in their colleges (Khalsa, DAV, Islamia) in an attempt to try to weed out nationalist thought. But it was not to be. The massive economic success of the canal/irrigation projects not only transformed and enriched certain groups but at the same disenfranchised many others, especially the urban middle class Sikhs and Hindus, who were the backbone of Lahore’s economy.

The British state was strong and able to quash most rebellious ideas before they became widespread but in 1907 as a result of a number of pieces of legislation that further pressured and alienated the very population of rural Punjabis that the security of India depended on, violent protests broke out in the Canal Colonies. The cause was championed and given an anti-Raj colour by leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai in Lahore. The British were caught flat footed, and unprepared. Repression and suppression followed quick smart which for a few years seemed to work.

But after WWI Lahore continued to gain a reputation not only for high quality education and culture but as a political hot bed. So much so that its reputation spread far and wide. In 1922 newspaper a rural newspaper in faraway Australia reported “The visit of the Prince of Wales to Lahore, which has been looked forward to with deep anxiety by those responsible for his safety, will, it is believed not be marred by disturbance of any kind. The tension has relaxed in the native city in the past week and it is too much to expect a general attendance of Indians to join the official welcome on Saturday afternoon for Lahore is the notorious centre of political unrest in Northern India but the Prince will not touch even the fringe of the bazars during his four days stay.” (Tweed Daily, Muwrillumbah 25 Feb 1922)

Around that very time T.E. Lawrence (of Arabian fame) was reported to be in Lahore and causing trouble in Afghanistan. Indeed, possibly in the very weeks leading up to Lawrence’s stealthy escape back to England, a young Sikh revolutionary who had been educated in Lahore, Bhagat Singh, assassinated a senior British police official in a case of mistaken identity. Though he escaped and a few months later exploded several smoke bombs while the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi was in session, he allowed himself to be arrested and imprisoned by the Indian government. Using his imprisonment and trial to denounce the Raj, Bhagat Singh became a national cause celebre. Anti-British protests broke out all across India and the chant “Bhagat Singh ke khoon ka asar dekh lena Mitadenga zaalim ka ghar dekh lena” (Wait and see, the effect of Bhagat Singh’s execution: The tyrant’s home will be destroyed, wait and see) became a popular public cry. Though he was hanged in 1931 for his crime, Bhagat Singh’s trial and resistance to colonial oppression made him an exhilarating figure around which the nationalist and Independence movement rallied. Even today he is hailed as a beloved historic martyr across the political spectrum.

Culture and Arts in Colonial Lahore

Intrinsic to Lahore’s self-image is the world of art and culture. It has always been the cultural capital not just of Pakistan but at various times throughout the past, especially during the Mughal period, one of the major cultural centres in all of South Asia.

With the advent of the British, art and art education, like everything else in Indian life, became a project to be moulded into something that served Imperial outcomes. Most British administrators and educationists dismissed Indian art as primitive or bizarre. In the words of John Ruskin, British artist and critic, the only art Indians were capable of was drawing ‘an amalgamation of monstrous objects’. As such, British administrators saw yet another deficit gaping to be filled. In 1875 the Mayo School of Arts, the first such institution outside of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, was established in Lahore. As in education more generally, the purpose of the school was “to initiate the native into new ways of acting and thinking” and of course provide skills that could be put to economic purpose.

John Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard, was appointed as the College’s first principal with a mission to introduce Western drafting and realistic drawing skills to traditional artisans and craftsmen. Kipling himself saw much to admire in Indian art and did what he could to promote it among his colleagues and students, all the while delivering a skills-based, industry-facing curriculum which eventually included the new-fangled medium of photography.

Interestingly, Bhagat Singh, the young political radical had cottoned on to the great potential of photographic images to educate and mobilise the masses against the British. Prior to his arrest and trial, as leader of the radical Hindustan Socialist Republican Association, Singh had used a magic lantern, an early proto-slide projector, in his lectures and political activities. It’s intriguing to consider that perhaps it was a piece of equipment that the Mayo College of Arts had introduced to its students and wider public in Lahore.

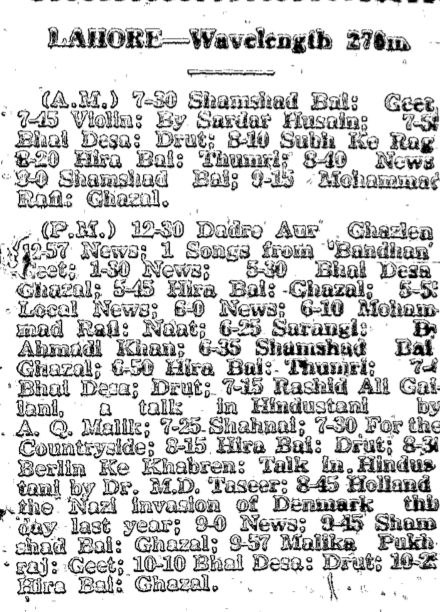

Lahore was a part of the classical music circuit of music conferences which brought a range of classical artists together to perform and compete. The local All India Radio station broadcast live sessions of local residents such as the eminent female singer Roshan Ara Begum and sitarist Ghulam Hussain Khan. And not just classical music. Three years before he broke onto a film scene he was to dominate for the next three and a half decades, in May 1941, a young Mohammad Rafi had a gig singing live on Lahore’s All India Radio station at 9:15 am and again at 6:10 pm.

But it was not just formal art education. Lahore was a city famous for its writers and poets. Its poetry reciting contests, were famous across north India and drew poets, as well as audiences, from far and wide. Music, especially classical music, had a long history of patronage in Lahore. The Bhatti Gate area in the old city, from where some of the earliest film personalities emerged in the early 20th century was renowned for its venerable tradition of classical music. Such luminaries as Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, considered one of the finest voices of modern times, Pandit Amar Nath, and later the brothers Amanat Ali and Fateh Ali Khan of the Patiala gharana, entertained listeners often in their own homes.

Indeed, the city was in love with music. So important a musical centre was Lahore that by the 1930s and 40s several international record companies including Columbia, RCA and HMV had offices in Lahore. The city had been on the talent recording circuit for European companies as early as 1904-5 when two Europeans, William Sinkler Darby and Max Hampe, representatives of Gramophone Records, popped up in Lahore. They made a large number of recordings of women singers, apparently tawaifs (courtesans) who had entertained men for centuries in Lahore’s fabled red light district, Hira Mandi (Diamond Market). In 1906 an ad in a London newspaper read as follows:

Shunker Dass &Co. Nila Gumbaz, Lahore, are prepared to invest a considerable sun, in conjunction with a thoroughly practical firm of makers or factors, to open a Manufactory in India, in order to supply the ever increasing demand for talking machines.

It seems Mr Shunker Dass was unable to generate the capital to set up his talking machine business, as records were known in those early days. But such an ad is evidence of Lahore being on the cultural radar that not only did Mr Dass feel confident to advertise in England but that he had the vision to see an opportunity that was just beginning to emerge when he ad was placed.

With a sizeable but not overly large population of European and American residents, Lahore attracted performers from around the world and catered to the needs of its non-Indian community. According to the Melbourne Age in January 1947 one of that city’s citizens, a dance instructor by the name of Frank Webber, was on his way to Lahore for a season of dancing at one of the city’s prominent hotels, Falettis. The city regularly hosted travelling dramatic troupes from Europe and America in its theatres not to mention the British community’s love to amateur theatrics which added to the city’s cultural lustre.

Much of the music and poetry and dance took place in and around Hira Mandi, the city’s famous red light district and from whose residents the film industry drew many of its musicians, singers and actresses. During the early days of cinema, actresses who had originally come out of the world of traditional dance, gave recitals to great acclaim and massive audiences before and after their movies.

One local dance troupe the Opera Dancers founded by a Siraj Din from ‘a poor family…passed his matriculation from Punjab University in 1932 and started a troupe to entertain the public with Sarla (a famous danseuse) as his chief artist’. Pran Neville in his book tells of how Miss Sarla drove audiences wild in between shows at local cinema houses

Responding to the loud applause of ‘Mukarar’ (Say it again) from the audience, Sarla advanced gracefully towards the front of the stage. With the burst of a song she turned around with such vigour that the loose folds of her gown expanded and the heavy embroidered border with which it was trimmed fanned out from her waist, showing for an instant the alluring outline of her lower form. She displayed remarkable muscle control and coordination as she worked herself up to reach the climax of her dance. The music went on in waves of tumultuous sound, with the musicians falling more and more under the hypnotic influence of their instruments, crying out ‘Wah Wah-Shabash’ to encourage the dancer. The audience burst out in applause, which manifested itself not only by loud clapping but by the showering of coins onto the stage. The tinkling sound of the coins drove the musicians to a new pitch of enthusiasm just as Miss Sarla made her exit.

Siraj Din and Ms Sarla and the Opera Dancers featured regular shows in Lahore but also entertained Indian and foreign troops during wartime through a special vehicle he called Fauji Dilkhush Sabha (Soldiers Happyheart Association).

V.D. Paluskar and The Gandharva Mahavidyalaya

The story of V.D. Paluskar, one of the most significant figures in modern south Asian cultural history probably illustrates better than any other the sort of city Lahore was in the early part of the 20th century and how many of the necessary elements for a film industry came together in the city. Paluskar himself had only a tenuous relationship with the film world but as an influential cultural figure his ten year sojourn in Lahore is a wonderful window into how the city provided the perfect environment for new cultural ideas.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar was born into a traditional musical family in Maharashtra, western India in 1872. Fired with a deep spiritual need to blend traditional classical music, Hindu devotional practice and education Paluskar was in essence a missionary of sorts. After spending the first 24 or so years of his life as a paid musician in the courts in several small princely states in southern Maharashtra he set out on his own to find a different sort of patron then the small minded autocratic and often musically limited petty royalty his family had been used to serving.

On his travels through western India, Paluskar encountered, at a hilltop shrine, a Hindu ascetic who among other things advised him to head north and to the Punjab in particular. The ascetic instructed him to set up a school in order to live out his destiny. And so the young singer headed north stopping to perform and build his reputation in Gwalior, Delhi, Amritsar and the market center, Okara. In 1898 he made one final move, 130 kilometers NE to Lahore where he began immediately, despite knowing no one or speaking any of the city’s three main languages (Punjabi, Urdu and English), to put together plans for the establishment of a music school.

His choice of Punjab’s capital—now in the midst of rapid development and growth under the British—was unlikely to have been random. Even though he had no connections, the city was well networked and open to exactly the sort of innovative, even revolutionary ideas, Paluskar had banging around in his mind.

To get his idea of a school off the ground he had to raise money and so turned to the middle class Hindu community who were embracing Hindu reform movements like the Arya Samaj which, though founded in Gujarat in Western India, found Lahore to be one of its most important, if not most important site in north India. Arya Samajis were urban and salaried and had both the education and the money as well as the motivation to support causes like Paluskar’s musical-devotionalism. Lahore’s fast developing reputation as a city of education, politics and economic opportunity meant that the the elite and rulers of the many princely states from Baluchistan, Kashmir, and Punjab maintained ties and often residences in the city. Many, especially the maharaja of Kashmir offered Paluskar and his academy, the heavily Sanskritised named Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, critical financial support and patronage.

And though he may not have been conversant in Punjabi or Urdu, Lahore was attracting migrants from all over India. Its economic and strategic rise in importance meant that national vernacular newspapers often had correspondents reporting on events in the city. One such Marathi newspaper, Kesari, began publishing stories about Paluskar’s activities. And though most of his students were local , many were immigrants like himself from Maharashtra including a large number of Parsis who though small in number were prominent as retailers of European goods and services, including owners of Lahore movie halls.

That Lahore and western parts of Punjab were heavily Muslim also had an appeal to the Hindu activist. Paluskar’s entire understanding of north Indian music was that it only could be truly understood and appreciated when performed within the context of a personal Hindu faith. Furthermore, Hindustani classical music, not to mention most of Indian culture, had been debased by Muslims . He believed Muslims performed music only for entertainment and often risque, morally suspect entertainment like courtesan dance recitals, at that.

Paluskar’s vision of a purely Hindu musical world was influential. In nearby Jalandhar where India’s first annual musical festival the Harballabh festival had since 1875 been a place where Punjabi musicians of all creeds and persuasions, but especially Muslim dhrupad artists, performed, Paluskar’s sectarian and vigorously anti-Islamic/anti-Punjabi stanct, made the festival unwelcoming for some of the greatest Muslim classical musicians of the era.

Though Paluskar’s vision and mission could be interpreted as being conservative and traditionalist in that it sought to reclaim the north Indian music system from Muslims and restore it to its rightful place as part of true Hindu faith and practice, (however, contentious that position was/is) there were several elements that should be seen as radical. The most important being his musical notation system. North Indian classical music has traditionally been an oral tradition; Paluskar himself never received formal training and his own teacher never even shared with him the names of the ragas he was learning. It was a secretive and territorial business with performers and gharanas fiercely committed to protecting their styles, innovations and knowledge. This was done through a guru to whom a student devoted his life and fulfilled the role of servant until he was accomplished enough —after many years—to take on his own students. Unlike in Western music, no music notations had ever been committed to writing.

Paluskar’s musical notation system, which he had begun to put down on paper while living for some months in Okara, became of his first projects upon arriving in Lahore. With the support of Hindu supporters, Paluskar was to publish the system which formed a fundamental part of the curriculum of his school.

The Gandharava Mahavidhalaya became another of Lahore’s many and varied educational institutions. It offered a rigorous traditional 9 year (!) course of intense training but also shorter teacher training courses called updeshak, for poor students. The school also actively recruited middle class women, revolutionary step for the time. Paluskar not only used the press to promote his work but tapped into the booming printing industry of Lahore to publish short instructional texts in pamphlet form on various instruments and music themes.

His student body grew and included a relatively large number of women and especially Parsi women but also Maharashtrians who had migrated to the city. Within several years his school was well established and financially sound but Paluskar still felt he needed a higher national profile if he was to really have an impact. Once again, Lahore, his adopted city, was able to provide the opportunity.

In 1906 a ‘durbar’—a public ceremony to honour the visit of royalty—was organised to mark the birth of King George V’s son. Paluskar recognised that if he could get on the program as part of the entertainment the eyes and ears of the entire country would be upon him. Through his own Lahori and royal connections he was able to secure a 15 minute slot which he used to promote his vision and school even further. By 1907/8 his school was not only well established but the Paluskar name as a educationist, a Hindu cultural reformer, an innovator and as an accomplished singer in his own right was secure. Though he left Lahore to return to Bombay in 1908 where he set up another branch of the GMV, Lahore was the city in which, as the sadhu had predicted, he would meet his destiny. The GMV in Lahore continued to operate until 1947 and the Partition when it’s heavily Hinduised curricullum and patronage became unviable.

Several of Lahore’s greatest musical names such as Pandit Amar Nath had associations with the GMV either as students or instructors and throughout the 1940s contributed musical scores for Lahore’s film industry. Paluskar himself probably felt films were exactly the sort of entertainment classical music should NOT be associated with but before his death in 1955, his son, D.V., performed in two films, the most famous of which, Baiju Bawra, he surprisingly performed a duet with the Muslim vocal maestro Amir Khan!

Utterly fascinating Nate

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks mate.

LikeLike