The Flying Coach had just pulled out of Gujrat. Passengers were settling in for a couple hours of sleep before our arrival in Pindi. Quietly whispering to each other, fussing with their reclining seats. Yawning. I had a window seat. My head rested against the glass. Outside, pitch black.

The driver inserted a tape into the deck and a mix of recent Indian film songs competed with the post-dinner clamour. Indian film songs in Pakistan are hugely popular. Slowly the coach fell silent and the music was the only thing to be heard. One of the songs immediately caught my ear. It had a smooth, soft-rock sound with a steady disco pulse at the bottom. Definitely catchy. Much closer to Western pop than ‘classic’ Hindi film fare. The singers teased each other by asking, ‘Kaisa lagata hai’ (How do you like it?) and responding, ‘Achha lagata hai’ (I love it).

Pure earworm stuff.

Hearing the song again the other day, memories flooded back, not just of that road trip but of that general era. The very end of the ‘80s and the beginning of the ‘90s were hugely turbulent years in India. One دور (daur/epoch) was quickening to an end. The new age, still undefined, was just beginning to emerge.

Kaisa Lagata Hai, was a super hit from the 1990 film Baaghi (Rebel) and fit perfectly with the times. It is filmi music in transition. The song hints at the more international sounds that were soon to turn Indian film and popular music from an obscure sub genre to one of the biggest categories in the world. The cheeky, mildly suggestive lyrics cleared the way for the openly sexual content of the current scene.

Though many of the giants of the ‘60s and ‘70s were still in the game, all across the film world fresh young faces, alluring voices and disruptive attitudes were pushing their way into public consciousness. Kishore Kumar whose peak came in the 70s, was still recording as were the nightingale sisters Lata (Mangeshkar) and Asha (Bhosle). But Kishore’s son Amit, who won Best Playback Singer of 1990 for Kaisa Lagata Hai, was in big demand. Lata and Asha were still beloved but new arrivals Anduradha Paudwal, Alka Yagnik and Kavita Krishnamurthy were popular among the younger set.

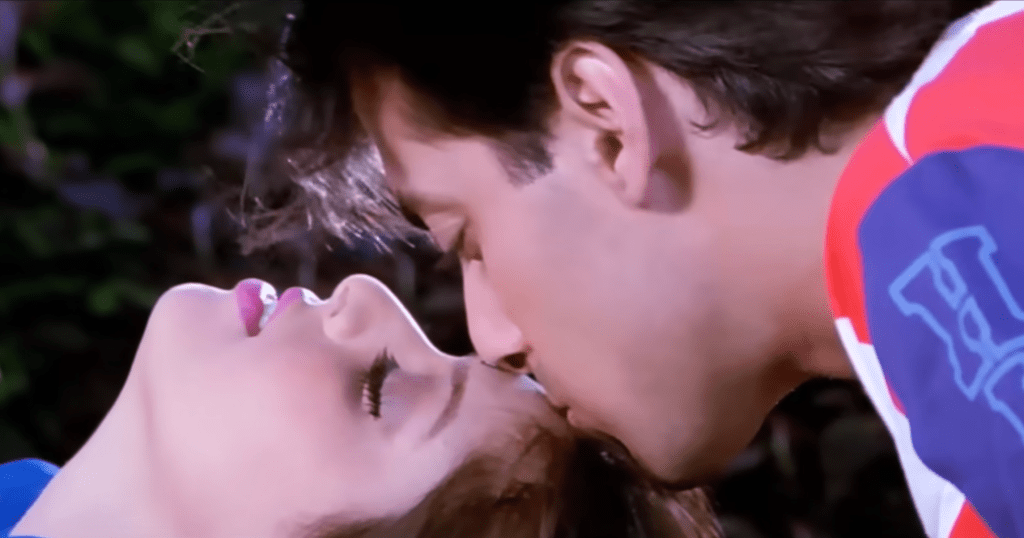

The scene from the movie in which the song was inserted depicted a country starting to creak toward a major makeover. The stars Salman Khan and Nagma were fresh and young. Salman’s red white and blue striped jumper clearly represented kids who looked to America rather than the Soviet Union as did many of their parents. They are shown shopping at Foodland one of Bombay’s early western-style supermarkets and buying large blocks of Toblerone chocolate…hitherto a rarity other than in Duty Free stores. Despite their new cool clothes and products their behaviour very much was still line with the flirty, cutesy comportment of previous eras; devoid of any adult sensuality.

**+**

India felt like it was going to explode in those years. Something had to give. There was so much potential being held back by an inefficient bureaucracy and the sclerotic “netas/नेता” (leaders) of Independence-era politics. The subterranean rumble of a vibrant business, media, creative and learned sector was impossible to ignore. The political system was fizzling with sparks and thick smoke while shooting colourful lower caste personalities who leveraged significant political influence, into the public realm. Something unstoppable was going on. India was changing. Perhaps too fast. Perhaps long overdue. But with no clear vision (yet) of the destination.

I lived in Pakistan at the time which was trying to cope with its own massively shifting tectonics. (Another story for another time.) Many of my holidays were spent in India, where I had been born and lived until the age of 17. As soon as you crossed the border the energy of a changing culture was everywhere to be seen, heard and felt.

Whatever you thought of Rajiv he was not your usual Indian politico. The Great Leader’s grandson, who flew commercial jets. Undoubtedly young and handsome but also henpecked by his fierce Italian wife. Rajiv was the first national leader with some actual experience of the world beyond Congress and JP politics. He was admired pretty much universally. For a few years anyway. With his blood connection to Nehru and Indira, Rajiv led the country to the base camp of the political Everest that would eventually be summited and claimed by Narendra Modi.

Mud vessels were replaced overnight by cheap bright colored plastic buckets. Tea was now always served in a porcelain cup or glass tumbler. You’d get it in a clay mutka only in certain out-of-the-way places.

Doordarshan, the stuffy national television station was being bruised up by Star TV and Zee TV. Networks that provided youth-centric game shows, music videos and reruns of international television hits. Bandits were in the news. Phoolan Devi and Veerapan. Multiple states were sites of ‘rebellions’: Punjab, Assam, Kashmir. Khalistan and Gurkhaland were put forward as new ideas. Naxalites seemed to be resurging in Andhra. Hand painted movie hoardings were quickly fading away. Digitally produced adverts choked off one of the great pleasures of being a film buff.

Everything was in flux. It was an edgy time. Assassinations of Prime Ministers. Caste politics. Phoolan Devi was sent to jail for her crimes against the upper castes but then was elected to Parliament. Elections, held once every five years, had been up to this point, a yawning affair in which Congress or Indira seemed always to win. But between 1996 and 1999 the country voted 3 times. Seven PMs took the oath of office in the 90s. Most of them lasted a year, tops. Some a few months. A fatigued shopkeeper in Mysore sighed deeply as he gave me my change, “Too many elections.”

India as a real center of global power and influence was still largely rhetorical but everyone knew it was only a matter of time before the ‘old ways’ of running India were shredded for good. Looking back, it was a generational change. A transition from a solid base built by a single political organisation and its most prominent family, to skyscrapers, flyovers, Pepsi and the birth of India’s billionaire class, Ambanis jaise. Hard to believe today the Nehru/Gandhis could ever have been relevant and admired. Narendra Modi was a state based political apparatchik at the time but the wave he would ride to successive victories was starting to swell. A group of young men talked loudly to me as we rode a train through central India. The Muslims had it coming. They were tricky and dirty and evil minded. This is a Hindu country.

**+**

Pop music, which in India equates to filmi[1] music, was sounding different too. A decade earlier the first lightning bolt to electrify the airwaves struck in the form of a 15yr old Pakistani girl singing the catchy, Aap Jaise Koi (Somebody Like You) in Qurbani (Sacrifice), the biggest movie of 1980. With a sound that mirrored perfectly the soft rock heard on American AM radio in the mid-70s (groovy bass, scratchy rhythm guitar, synth, soaring melody lines) the singer (Nazia Hassan) and producer/composer (Biddu) went on to become international stars throughout the 80s. Disco-lite had arrived in India.

A transition from the founding fathers and sons of Hindi film music, to a new crew of shamelessly self-promoting producers/writers/composers like Bappi Lahiri began chipping away at the thick walls that had protected film moguls from even considering changing their decades-old formula. Four voices[2], two female and two male, had completely dominated filmi music since the 60s. The soundscapes in which they were asked to sing were equally dominated by Indian instruments and compositions based upon classical ragas or Punjabi/Bengali folk songs. If Western sounds and instruments were heard it was to signal the arrival of the vamp or the Vat 69-drinking villain.

Bappi Lahiri was a different kind of music director. He reveled in excess. As big as Barry White, he draped himself in bling, wore flamboyant shades 24/7 and embraced the wildest ideas. A true disrupter. He could compose in the comforting, long-standing sound of the 50s-70s with real conviction and skill. But a trip to a nightclub in Chicago in 1979 changed his career from a respected composer/arranger into the badass of Bombay. “After a Chicago show,” Bappi told an interviewer. “We went to a club. A DJ was playing the most amazing music. Something completely new and fresh. John Travolta and the Bee Gees. I asked him what this was and he said, ‘Disco.’”

Disco hit Bappi hard and upon return to India he introduced its thumping beats into nearly every one of his projects. If Biddu had snuck sweet Western pop melodies into Qurbani, Bappi turned the volume up to 11 and exploded woofers from one end of India to the next. Bappi was shameless. For the rest of his career his name was synonymous with upbeat, percussive dance music. Though the “Disco King’s” formula rarely strayed from a steady, 4 on the floor beat, and vapid, repetitious lyrics, there is no question that without Bappi Lahiri there would be no AR Rahman.

Huge as Bappi was (he died in 2022) it was technology that really laid the walls of filmi music to waste. Cassette tapes came to India later than the rest of the world. They started to appear in the late 70s but import restrictions and decades-old laws that promoted local manufacturing meant they were priced as a luxury item. Or at least the machines that played them were. But as demand increased some restrictions on manufacturing both tapes and tape recorders were lifted and Indian entrepreneurs jumped into the deep end with gusto.

In the winter of 1984 on a visit to Allahabad I was blown away by the carts of cassette tapes being hawked in every bazar in the city. Literally hundreds of titles by artists I had never heard of. Everyone was browsing and buying, even rickshaw walas, school kids and policemen, who until that moment had probably never owned anything but a radio. Especially popular was a genre called ghazal. Especially as sung by a husband and wife pair, Jagjit and Chitra Singh. Their tapes sold fast and new ones released just as fast. What was even more remarkable was that this was not filmi music.

Ghazals and Jagjit and Chitra may have been the most successful genre in cassettes but they were not the only style and type being bought up. All sorts of regional folk styles hitherto untouched by the major recording companies (EMI and Polydor), in every language and dialect under the Indian sun were suddenly available dirt cheap. Tapes with sexy lyrics, comedy tapes, religious chants and pop music by wannabe stars from small cities in the hinterland were available everywhere.

Not just a giant tech leap forward, the cassette boom must surely rank as one of the great economic stimulants of that period. Piracy helped the revolution along. What just a couple years before had been seen as a ‘foreign’ object for the well-to-do, was now available for a few rupees. This was a very exciting period to be a music lover in India. I could not get over the fact that here were the faces of Kishore and Rafi or Amitabh on a cassette cover, equally at home as Michael Jackson and the Rolling Stones .

In the words of Peter Manuel, whose 1993 book Cassette Culture: popular music and technology in north India documents this period of transition, “…cassette technology effectively restructured the music industry in India. In effect, the cassette revolution had definitively ended the hegemony of GCI,[3] of the corporate music industry in general, of film music, of the Lata- Kishore duocracy, and of the uniform aesthetic which the Bombay film-music producers had superimposed on a few hundred million listeners over the preceding forty years.”

Filmi music’s share of the market shrank immediately and dramatically to less than 50%. Indipop, as this new wave of non-film music was labeled, stormed into public consciousness. New stars singing in new languages, including loads of English phrases, new factories set up in places like Bhopal, Coimbatore and Dehra Dun opened thousands of new markets. It seemed filmi music was going to die a quick death. Indipop flourished, thanks to the plastic cassette and the arrival of what Indians call ‘liberalisation’.

By the late 80s, India’s protected and insular economy was no longer fit for purpose. All political parties understood this and in 1990 a process of doing away with the restrictive import duties, tariffs and allergic attitude to foreign investment especially in products valued by the booming middle class began. Satellite and cable TV showed foreign movies and TV shows. People with money could travel more freely and experience the same things people outside of India took for granted.

The film industry was given government financing for the first time in its 60 year history. More movies were being shot overseas. Sound quality of the music improved dramatically. Audiences thrilled to see their idols dance through the streets of Paris, Cairo and Sydney all in the same song! But filmi music held on. It learned from the changing times and by the early 2000s had once again grabbed back its near monopoly of the popular music market. Indipop stars, once the great ‘alt’ pop singers, were invited to sing in the films. The half dozen geriatric (though immensely beloved) singers who had ‘owned’ filmi music were steadily pushed aside, along with those folk and classical talas and sensibilities.

Songs like Kaisa Lagta Hai were among the first to move in a new direction. Kishore Kumar’s son, Amit, sang the male lead. Anuradha Paudwal the female lead. Amit eventually retired, blown away by the likes of Anu Malik, Kumar Sanu, Udit Narayan, Lucky Ali and in the late 90s and early 2000s exciting singers from Pakistan: Atif Aslam, Zafar Ali and Adnan Sami. Sophisticated, widely influenced and wildly talented composers, exemplified by AR Rahman were now firmly in control of the filmi ship. American and European audiences grooved to Jai Ho and Mundian Bach Ke. Bappi Lahiri’s compositions found new life in American/European songs like Addictive (Truth Hurts), Freeze (Madlib) and Come Closer (Guts).

And India today, whether you like Modi or not, is a true global power center and influence peddler. It all began when the floor of old India and the old Hindi filmi world fell away with the tentative arrival of songs like Kaisa Lagta Hai.

[1] Music and songs from Indian, mainly Hindi/Urdu language, movies.

[2] Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Mohammad Rafi and Kishore Kumar

[3] Gramophone Company of India, formerly known as His Master’s Voice, was until the late 60s the only significant producer of recorded music.

Welcome back old horse

Trust that life is treating you well

Many thanks for the homework!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Hal, Nice to hear from you. Happy New Year. May it be better than last. Hope you and yours are well and happy. take care, Nate

LikeLike